A translational science success story

Delayed school start times to begin this year in East Greenwich

PROVIDENCE – In 1991, with the ink barely dry on my Bachelor’s degree in Psychology, I started my first “real” job, as a research assistant for Mary A. Carskadon, Ph.D., head of the Emma Pendleton Bradley Hospital Sleep for Science Research Laboratory and Professor of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at the Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

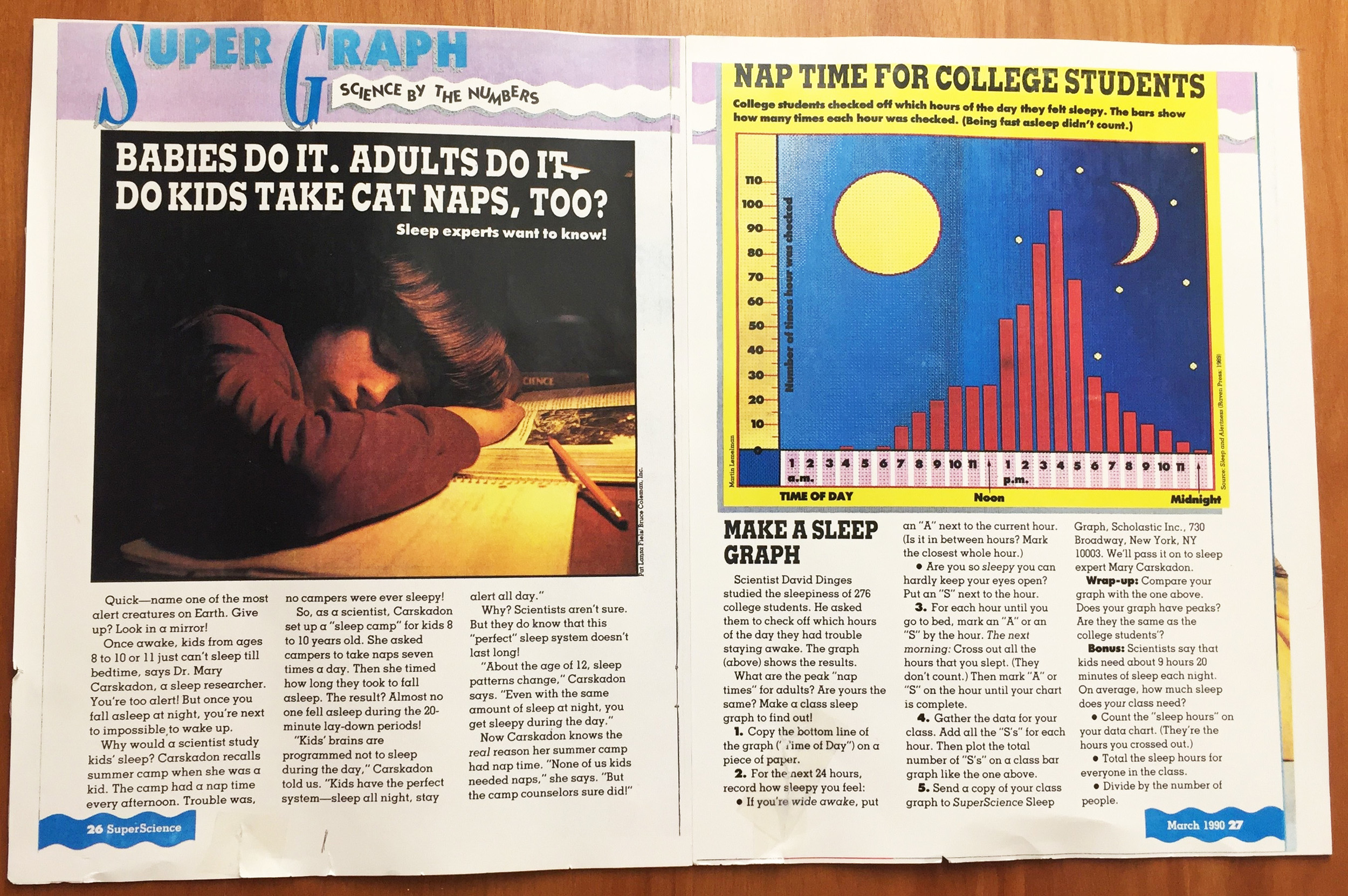

It was an exciting time at the lab. Earlier that year, after being featured in a science publication for school children called SuperScience Blue, Carskadon, along with her colleague Christine Acebo, Ph.D., had surveyed nearly 4,000 students from around the country about their sleep patterns.

They had a burning question that they thought this data set could answer: whether the delay in sleep patterns commonly observed in adolescents was related more to psychosocial factors – such as increased social opportunities and more homework – or to biological factors, namely pubertal development.

In their landmark paper, entitled “Association between puberty and delayed phase preference,” published in the journal Sleep in 1993, they showed that among sixth-graders, preference for staying up later at night and waking later in the morning was associated with students’ reports of more mature pubertal characteristics, and not to whether they had older siblings or attended a junior high or middle school, as opposed to an elementary school.

Carskadon and colleagues made the following conclusion in their paper:

“Early to bed, early to rise” may be difficult in the presence of a biologically driven delayed phase preference.

Furthermore, the widespread practice in U.S. school districts for school buses to run and for the opening bell to ring earlier at high schools than junior high schools, and earlier in junior high schools than primary schools, may run precisely counter to children’s biological needs.”

Wake up call sounded

And thus, a wake up call was sounded, and what could be called the “school start time revolution” had begun.

In the subsequent 25 years, Carskadon and other researchers from around the world have replicated and extended the results of this seminal study.

They have shown that during adolescence, the timing of sleep shifts later due to a delay in the internal biological clock, and the rate at which the body builds up sleepiness across the day.

Parallel to these scientific advances, educators and policymakers have taken note of their findings.

Community leaders have started to apply this research – often with sleep scientists and pediatric sleep medicine physicians at their sides – by delaying the start times of middle and high schools to better align with the teenage body clock.

Grassroots efforts to enact these changes are ongoing in 25 states. [See link below for a complete list and more information.

Translating basic science into a plan of action

It has been a thrill to witness the strides that my colleagues have made in translating their basic science findings into better health for the youth that their research aims to serve.

In the past two years, however, the topic of later start times for middle and high schools has taken a different turn for me. I now have established my own research career examining sleep and mood regulation and am a practicing sleep medicine physician.

I am also a mom. In March of 2014, I was approached by a number of other parents in my community to join with them in an effort to delay the start times at our secondary schools.

Finally, here was a chance for me to get my hands dirty working on the front lines of this problem.

Changing school times in East Greenwich

In just two short weeks, after two years of unrelenting efforts by many parents and school administrators [too many to name here], Archie R. Cole Middle School and East Greenwich High School will start at 8 a.m., representing a 30-minute delay in school start times from previous years.

Indeed, the East Greenwich School District will become the first public school district in Rhode Island to enact delayed school start times in their secondary schools.

It has been personally meaningful to me to see the science done by treasured friends and colleagues turned into policies that benefit my own children and the other students in my community – a true translational science success story.

Lessons to share

Along the way, I have learned a few valuable lessons to share with others who wish to work for delayed secondary school start times in their cities and towns:

• Elect school board members who are interested in evidence-based practices. This was a key to making this change in East Greenwich. When the later start time movement started in EG, several officials were skeptical about the science or were committed to preserving the status quo.

To make progress, we needed courageous people who would be willing to risk political popularity in favor of data-driven change.

Thus, parents who wanted to see best practices implemented for the betterment of our schools banded together to support school committee candidates who were committed to using data-driven policies to shape the educational environment for our youth.

Our present school committee is comprised of thought leaders who are involved in politics, not party-line politicians. This has affected not just the change in school start times, but many other innovations in our schools.

• Get ready to compromise. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends an 8:30 a.m. school start time, and although this would have been ideal, this is not the proposal that was enacted.

Nevertheless, those rallying for delayed start times should view an 8 a.m. start as an incremental victory – a substantial body of research shows that even a half-hour more sleep each day can help ward off the untoward effects of insufficient sleep.

• Prepare for conflict. There were many vocal opponents to the start time change in East Greenwich, representing dissenting viewpoints held by students, parents, and teachers and administrators.

Though a large body of evidence shows that delaying school start times is a cost-effective way to improve academic performance and reduce physical and mental health risk in teens, including risk of suicide, drug and alcohol use, and automobile accidents, it may represent a major inconvenience for some families.

Work schedules, extra-curricular activities, and childcare plans may need adjustment. Some youngsters may be thriving in the current environment, making it difficult for them or their families to see why the change is needed.

Be respectful of opposing viewpoints. Hope for respect in return. These are your neighbors, after all.

• Be in it for the long haul. Although dozens of people have worked for more than two years to see this change come to fruition, it is not time to rest.

Multiple studies performed in a diverse range of communities have shown the benefits of later school start times.

Nevertheless, in at least one school district in New York, not all of the initial benefits were long-lasting, according to a study of longitudinal outcomes of start time delay on sleep, behavior and achievement in high school, published this year in Sleep.

In this study, a 45-minute delay in school start times originally resulted in an average of 20 more minutes of sleep per student per night.

One year later, students had less tardiness and there were fewer disciplinary incidents, but sleep duration had decreased back to baseline levels.

More research is needed to determine how to implement school start time delays to maximize sustained benefit.

Toward that end, we are performing a longitudinal study of the students in East Greenwich to determine whether the start time changes increase sleep duration and improve other outcomes, and what factors drive optimal sleep in our student body.

Katherine Sharkey, M.D., Ph.D., is a sleep medicine physician at University Medicine and Associate Professor of Medicine and Psychiatry & Human Behavior at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.