Can brain science help Syrian children refugees build resilience to toxic stress?

Neuroscientists, anthropologists, historians and NGO advocates convene two-day workshop at Brown to explore potential interventions

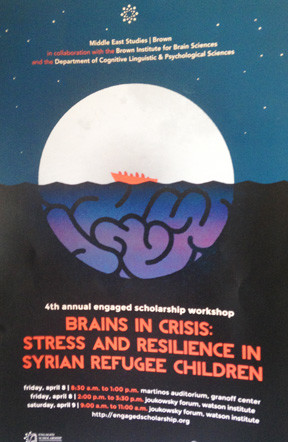

PROVIDENCE – The poster for the conference, “Brains in Crisis: Stress and Resilience in Syrian Refugee Children,” had a somber, surreal quality to its artwork.

At the center was a small, bright orange image of what appeared to be a boat of refugees, floating atop the surface of a sea of waves that, if you looked at it more closely, was actually a stylized image of the curves and crannies of the human brain. The stark scene was illuminated under the bright light of a full moon, surrounded by darkness.

The poster’s symbolic artwork captured the way in which the exodus of millions of refugees from the war-ravaged landscape that once was the nation of Syria has entered the political realm of our consciousness: a sea of contradictions amid the growing desperation of millions of victims swallowed up in a geopolitical conflict, a struggle that, in turn, has become caught up in the real politick of an American presidential race, where the fear of terrorism and xenophobia about foreigners has been exploited by many candidates in search of votes.

The two-day conference, held on April 8 and 9 at Brown University, was the fourth annual engaged scholarship workshop by the Middle East Studies department, a collaborative enterprise with the Brown Institute for Brain Science and the Department of Cognitive Linguistic & Psychological Sciences, in partnership with the Watson Institute.

The idea emerged from a serendipitous conversation between Dima Amso, associate professor in the Cognitive, Linguistic, and Psychological Sciences, and Beshara Doumani, the Joukowsky Family Professor of Modern Middle East History and director of Middle East Studies, about what could be done to intervene in a positive fashion to help promote resilience in Syrian children that were refugees, based upon the known biological interventions around toxic stress.

Or, as Amso posed in a question on a slide as part of her presentation: “Can we harness the power of cognitive and brain development research to further manufacture resilience in Syrian refugee children?”

A two-day, in-depth conversation

Throughout the two-day event, which was broken down into episodic conversations, with topics such as “Sciences and Solidarities: How did we get here?” and “Stress, Resilience and Crisis,” followed by “Stress, Trauma and Youth” and then “Limiting Negative Outcomes,” there was a rich denseness, a fecundity to the dialogue, which often began with speakers sharing their own perspectives – because there was so much basic information to absorb.

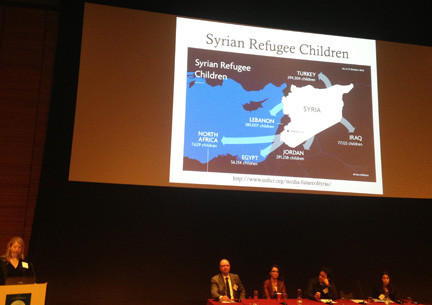

From the geopolitical side, the conversation began with an effort to define the landscape: identifying the size of the Syrian refugee population, where the refugees were now located throughout the Middle East, the differences in the Syrian refugee camps located in Jordan, the fact that many Syrians were still “refugees in place” in the war-torn world of what was once Syria, the shifting social and political pressures within the camps, such as the fact that many of the 13-to-17-year-old young males were often “missing,” having been recruited by different intelligence services.

There were also discussions about the conflicting realities of the camps, where children were often missing from school because of the need for them to support the families obtain the daily necessities of survival – and the dangers of trying to impose solutions that were “helicoptered” in from outside the camps’ reality.

Tala Doumani, a junior at Brown with a double major in International Relations and Social Analysis and Research, in her opening talk, “Reflections on the Syrian Refugee Crisis in Jordan,” spoke about the emotional need for nurturing and human contact that many of the young women refugees sought, seeking to bond with outside visitors, including herself.

Despite the physical isolation of the refugee camps, there was also a sense of revelation about the interconnectedness of the digital world, with its new kind of engaged community being created on social media, and how it could connect the refugees with the rest of the world.

As Amso told the story, one young woman refugee asked her, as she was departing the refugee camp in Jordan: was Amso was on Facebook, so they could connect and continue their conversations?

From the historical side, there was the growing realization that the definition of countries and nations, once clearly defined by neocolonial forces, no longer necessarily existed with the same kind of boundaries anymore.

And, from the brain science side, there was a growing understanding of how the brain, with its superb sense of timing in normal growth, reacted to stress, with a rewiring of signaling patterns, growth patterns and epigenetic changes.

It was the kind of basic primer that is missing today from so much of the news coverage and the political dialogue.

A meeting of the minds

The “Brains in Crisis” gathering brought together a talented group of neuroscientists with an equally impressive group of on-the-ground children’s advocates working with Syrian refugees in Jordan from an array of NGOs.

On the brain science side of the equation, the speakers included:

• Bruce McEwen, the head of the Laboratory of Neuroendocrinology at Rockefeller University, talking about “The Brain on Stress: Protection vs. Damage”

• Audrey Tyrka, director of the Laboratory for Clinical and Translational Research at Butler Hospital and professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at Brown University, talking on “Early Life Stress and Cellular Aging: Risk and Protective Mechanisms”

• Megan Gunnar, director of the Institute of Child Development at the University of Minnesota, talking on “The Protective Role of Relationships in Stress Regulation and Brain Development”

• Carl Saab, associate professor in research at Brown University and Rhode Island Hospital Departments of Neuroscience and Neurosurgery, talking about “A Neuroscientist’s Perspective on a Humanitarian Crisis,” focused in part on his lab’s work studying brain mechanisms in animals and humans; and

• Kevin Bath, assistant professor in the Department of Cognitive, Linguistic & Psychological Sciences at Brown University, talking about “The Use of Translational Models of Early Stress To Identify Markers of Risk and Resilience.”

Also presenting was Brown University President Christina Paxson, who spoke on “Why Adversity in Childhood Matters.”

In the audience were Diane Lipscombe, the newly appointed director of the Brown Institute for Brain Science, and Nasser Zawia, dean of the Graduate School at the URI College of Pharmacy, whose research has focused on the latent effects of environmental insults on the developing brain, and discovery of a novel class of mechanism-based rugs for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease.

On the ground in Jordan

On the NGO side of the equation were Frank Roni, child protection specialist, UNICEF Jordan; Curt Rhodes, founder and director of Questscope for Social Development in the Middle East; Kate Washington, independent consultant with UNHCR MENA Bureau, and Marcia Brophy, regional mental health and psychoscocial support specialist for the Middle East and Eurasia, with Save the Children International.

Their presentations included discussions of what vulnerability modeling can and can’t do and the limits of using data to design and target assistance for Syrian refugees, and the on-the-ground realities of responding to children’s needs and the practicalities of delivering mental health and psychosocial supports in protected conflicts.

One revealing segment of the talk by Brophy talked about the results of survey conducted with Syrian refugee children about what made them happy and what made them sad.

The conference also included two closed-door discussion sessions for invited participants, which focused on the potential next steps that might be taken as a result of the workshop.

Moving forward

ConvergenceRI sat down with Dima Amso on the afternoon of April 8 to talk about potential future plans for action coming out of the conference.

ConvergenceRI: Where do you go from here?

AMSO: That’s what the [closed] discussions are about. It’s a very difficult question, but it’s a question that I think is worth asking.

It’s important to take the privilege of being a scientist in an amazing place like Brown, to take what we know, and to see whether it is applicable in a crisis situation. To put our weight behind any crisis situation where kids are suffering, be it here in Rhode Island or be it abroad.

Exactly how you do that may not be answered today, it may not be answered tomorrow, but it may open the door for an answer that takes a little while longer to completely formulate.

Anything good doesn’t happen in a day and a half of people talking. Yet, we’re moving on the right track, and I think that’s what we can accomplish here.

ConvergenceRI: I was just talking with Audrey Tyrka, and I asked her the same question, about where do you go from here, particularly in conversations around toxic stress here in Rhode Island. She talked about the potential to perhaps get the new Hassenfeld Institute to pivot and focus on toxic stress.

AMSO: I think that would be fantastic. I think it would it cover a lot issues in the state of Rhode Island, it would be inclusive for a lot of children who are experiencing stress from a variety of different arenas – a difficult home environment, bullying in school, lead exposure, nutritional deficiencies.

And, to address that as part of children’s health at the Hassenfeld Institute, I think it would really have broad-ranging impacts on a lot of kids.

ConvergenceRI: How does the conversation get changed? I interviewed Sen. Jack Reed today at the tour of a virtual reality lab two blocks away, he was traveling with the director of the National Science Foundation, and Reed told me that he was unaware that this “Brains in Crisis” conference was happening. I wondered: would it be possible to drag him away from the schedulers and ask him to stop by? How do you make such connections happen?

AMSO: I went to Dr. Phyllis Dennery’s talk last night [on April 7], it was a faculty-to faculty talk at Brown, where she talked about the role of toxic stress in health outcomes and infant mortality rates in the United States. She’s the new [pediatric] director of Hasbro Children’s Hospital, and, effectively, she could have given a talk at today’s sessions, no problem.

It would have fit in absolutely perfectly. And, I thought to myself, there are so many synergies, and it’s hard to know what’s going on, even in such a small place like Rhode Island.

It’s the eternal question: we’re all searching for each other. Even in the digital age, we’re all Facebook. It’s hard to create one unified approach.

ConvergenceRI: Are there examples where research has converged?

AMSO: One thing that has happened, for example, is the unified approach in research around autism, RICART [the Rhode Island Consortium for Autism Research and Treatment].

If something like that could happen within the arena of toxic stress – you’ve had this idea before, of course – it would be [wonderful].

It would take funding; you would need to hire people. RICART did it with a gift from The Simons Foundation. You need to hire people to bring in the community, it’s very important, for scientists to hear the community’s needs.

I think it could be fantastic, but it would need to coalesce with a lot of structural support. And, I think it would be hard to do from a top-down approach; you really need to build it from the bottom up.

ConvergenceRI: In terms of applying the biological knowledge of how to counteract stress, listening to the descriptions of situations of what’s happening on the ground in refugee camps, it does not seem as if it will be a simple equation to “manufacture resistance” to stress in children, because of the political and social realities.

AMSO: I am a firm, firm believer in lifestyle changes that support health. I think that’s not a controversial thing to say.

Lifestyle changes are how doctors prefer to treat heart disease. So, if you’re comfortable with treating heart disease that way, through lifestyle changes and habit formation that’s more positive, I don’t see any reason why couldn’t we approach the brain’s experience in the same manner, in addition to psychosocial and mental health treatments – not in lieu of, but in addition to them.

We have a lot of information about what lifestyles are supportive of brain health. To me, it’s in line with [the philosophy of] do no harm; it will not do any harm to have a child do cardiovascular exercises daily. It will not do any harm to have high nutrition diets. It will not do any harm to get proper circadian rhythms in your sleep cycle. Those are all things that have been shown to buffer children [from toxic stress].

These are the things, the healthy principles of human development. To me, this is something that I think is worth pursuing, not instead of, but in addition to what is currently being pursued.

The changing political landscape

ConvergenceRI also sat down to talk with Sarah Tobin, one of the five organizers who put the conference together. Tobin is an anthropologist; her work explores transformations in religious and economic life, identity construction, and personal piety with at the intersections of gender, Islamic authority and normative Islam.

ConvergenceRI: Where do you go from here? I’ve often found, that once you bring people together, they tend to revert to their own, previous behaviors, retreating to their silos, which are more comfortable. Is there a plan of action?

TOBIN: We spent a lot of time today attempting to define what the best questions are to ask. There is a challenge, which is that these communities do not always communicate well with each other.

It’s not necessarily part of the process of the administration of humanitarian aid in crises. And disasters such [as with the Syrian refugees] would not necessarily involve neuroscientists or brain development specialists.

It’s not a typical part of the process. What we’re trying to do is unique and innovative for no other reason than we’re bringing people together who don’t typically talk to each other.

ConvergenceRI: What is it like when you bring people together who don’t normally talk with each other? What makes an engaged community, particularly in the scientific and scholarly world?

TOBIN: I think that, for a number of folks in the room, the scholars and the academics in the room, the ethical dimension of the work that we do is about doing it right, and doing it well, and doing it with communities that need or want that information, or benefit from being in the conversations.

Which is how I ended up working on the Syrian refugee project.

My academic research in Jordan is actually focused on the Islamic economy. I look at banking and financing. I’m an anthropologist, and I do economic anthropology; I’ve been working in Jordan since 2005.

I’m not a refugee scholar. But I realized, when I started going back to Jordan in 2013 and 2014, as the Syrian refugee crisis was [escalating], that being an ethical scholar in Jordan meant paying attention meant paying attention to the things that the Jordanians were paying attention to.

I started to take into consideration the kinds of questions and concerns that were vexing to my colleagues and friends, and that meant paying attention to the Syrian refugee crisis.

And, I think that this is the kind of moment that a lot of folks in the room today are also having – which is, to be an ethical scholar of brain development, or of neuroscience, or whatever fields of history and other social sciences the scholars are from, it requires being engaged ethically as global citizens, as moral citizens, as someone who is generally concerned about the future of the world.

The future of, certainly, in the United States, thinking about the impact of Syrian refugees is having on the U.S. political discussion.

It requires paying attention. The Syrian refugee crisis has been considered the worst humanitarian crisis of our generation, of our era.

Taking account of that, people then bring the skills that they can, the attention that they can, the sciences, the morals and ethics that they can. And, I think that’s the driving force behind this project.

ConvergenceRI: So many of the boundaries of modern countries in the Middle East were developed as part of the Sykes-Picot secret agreement drawn by the British and the French during World War I. As a result, many of the ongoing conflicts in the region have their roots those post-colonial boundaries that were once imposed on the Middle East.

In many ways, the definitions of what a county is and what a nation is in the Middle East is changing and evolving now, according to religious and ethnic identities. For instance, at what point do the Kurds have their own nation?

TOBIN: One of the lessons of the Syrian conflict or civil war and the refugee crisis is that it challenges fundamentally what a nation is or what a state is. And, perhaps, these neocolonial models don’t work anymore.

I opened my part of the discussion this morning with an overview. Many people still need the basics: where is Syria on a map, where is Jordan on a map. It needed to be given, because the background, that context, many people don’t really know.

I think it’s particularly important to keep in mind the way that the Syrian refugees are used as pawns in the current political climate – the idea that Syrian refugees have become a political tool, with Presidential candidates using them to try and further a xenophobic agenda, an anti-Islamic agenda, one that say foreigners are not welcome here.

But the fact is, Syrians are the victims here, they really are.

It’s sometimes hard for people in the West to see young, health men who are 16, 17, 18 years old as victims. But the fact is, they are. When this conflict started, they were all 11, 12, 13.

There are certainly a large group of young men, who once they became old enough to be conscripted into Assad’s army, they said no, and they left, because they didn’t want to be complicit in the actions of the Assad regime.

Knowing that context, and knowing the age of conscription, this is really important in terms of understanding [the roots] of this refugee crisis.

The problems need to be addressed in a very holistic fashion. The NGOs we had here are amazing; they are committed, individually committed, to building strong organizations. They spend their days, their nights, their weekends, immersed in these issues.

We have the space, as academics, to jump in and jump out. Even though I’m committed to Jordan, and I’ve been going back and forth for more than a decade, the fact is, I still have the ability to go in and go out. These folks are committed to being there day and day after day. I admire them.

ConvergenceRI: One of the things that I learned in my work in communications and outreach is that it is often easier to attach a message to an existing channel than to try and attempt to build an entirely new channel. Has the group explore a potential collaboration, say, with Edesia, a nonprofit manufacturer in Rhode Island of nutritious food products that are being distributed to refugees from Syria. They are already on the ground, they have connections.

TOBIN: There was someone here today from Edesia at the conference. These are the kinds of connections that we’re trying to build.