Finding common ground on future food policy in RI

With the state’s first food strategy in the works, the connection between achieving better public health outcomes may hinge on the integration of commercial kitchens as a community classroom and pulpit for promoting an olive oil, plant-based diet

Changing diets and changing patterns of behavior often require broader cultural changes related to family patterns, from grandparents to children and everyone in between.

PROVIDENCE – When it comes to promoting food, food culture and the glorious bounty from its food ecosystem, Rhode Island had many of its best assets on display on Saturday, Aug. 6.

It was a crowded morning in Lippitt Park, at the Hope Street Saturday Farmers Market, one of some 55 farmers markets operating in Rhode Island, where a steady stream of shoppers eagerly browsed the displays of fresh produce from more than 50 vendors, despite the humid weather.

Indeed, there is an impressive network of farmers markets now operating across the state, complemented by a growing number of restaurants with menus committed to bringing food fresh from the farm to the table, according to Farm Fresh RI.

“We believe that every Rhode Island family should be able to take part in the fresh bounty of veggies, fruit, herbs, eggs, meats and cheeses produced by our local farmers,” Farm Fresh RI’s website says, proclaiming that the state’s farmers are the key to both vibrant cities and a vibrant countryside, strengthening the environment, health and quality of life.

Farm Fresh RI’s mission in part is to build an organized network to distribute farm fresh produce through a variety of innovative marketing approaches, seeking to overcome the food deserts and food swamps that dot Rhode Island’s landscape.

The farmers market in Lippitt Park, said one shopper from Cumberland, a grandfather, accompanied by his wife and their two grown daughters, one visiting from Seattle, Wash., the other from Warren, carrying her six-month-old son, who in turn was captivated by the sounds of an acoustic band playing fiddle music, was simply “one of the best things about living in Rhode Island.

A culinary haven, not just Haven Brothers

Rhode Island has emerged as a kind of culinary haven for restaurants and food trucks, driven in part by each new class of chefs and restaurant workers graduating from a local university, Johnson & Wales.

Rhode Island’s 3,000 restaurants generate a collective $2 billion in annual sales, according to a recent Brookings Institute analysis.

Some 77 percent of the 170 million Americans that are said to be “leisure travelers” are classified as culinary travelers, seeking out food festivals, memorable meals and other food-related experiences as a key part of their travel plans, according to the American Culinary Traveler report published by Mandala Research.

In India Park on Saturday afternoon, Aug. 6, the proof was in the pudding – and in the beer, so to speak, as there was a veritable rodeo of food trucks participating in a Food Truck and Craft Beer Festival, attracting an overflow crowd, including Stefan Pryor, secretary of CommerceRI, who perused the scene.

Two hundred yards further down the waterfront, Pryor had also visited the pop-up market at the future site of the proposed Rhode Island Central Market, at the former location of the Shooters nightclub, now the location of the water ferry between Providence and Newport docks.

The impromptu market featured an eclectic mix of 28 local Rhode Island food and beverage businesses, from Dell’Orto Extra Virgin Olive Oil to Yacht Club Soda, from Fox Point Pickling Co. to Narragansett Creamery, from Mumma’s Real Lemonade to the Ocean State Smoked Fish Co.

In addition to Pryor, there was a steady stream of consumers to sample the wares at the pop-up market, including Neil Steinberg, president and CEO of the Rhode Island Foundation, Grace Lentini, managing editor of Providence Monthly, and Congressman David Cicilline.

The night before, as there is every Friday night during the summer, there had been a gathering of food trucks in the Roger Williams Park Carousel Village, with some 30 different food trucks appearing on a rotating basis.

[Saturday night was also WaterFire, with a full display of more than 80 braziers lit, sponsored by Rhode Island Defeats Hep C, bringing thousands of visitors to downtown Providence and to partake of its numerous restaurants. On Sunday, for the Providence Flea Market, held on the greenway that is part of the former Route 195 reclaimed land, also featured a bevy of food trucks.]

Defining the RI food sector

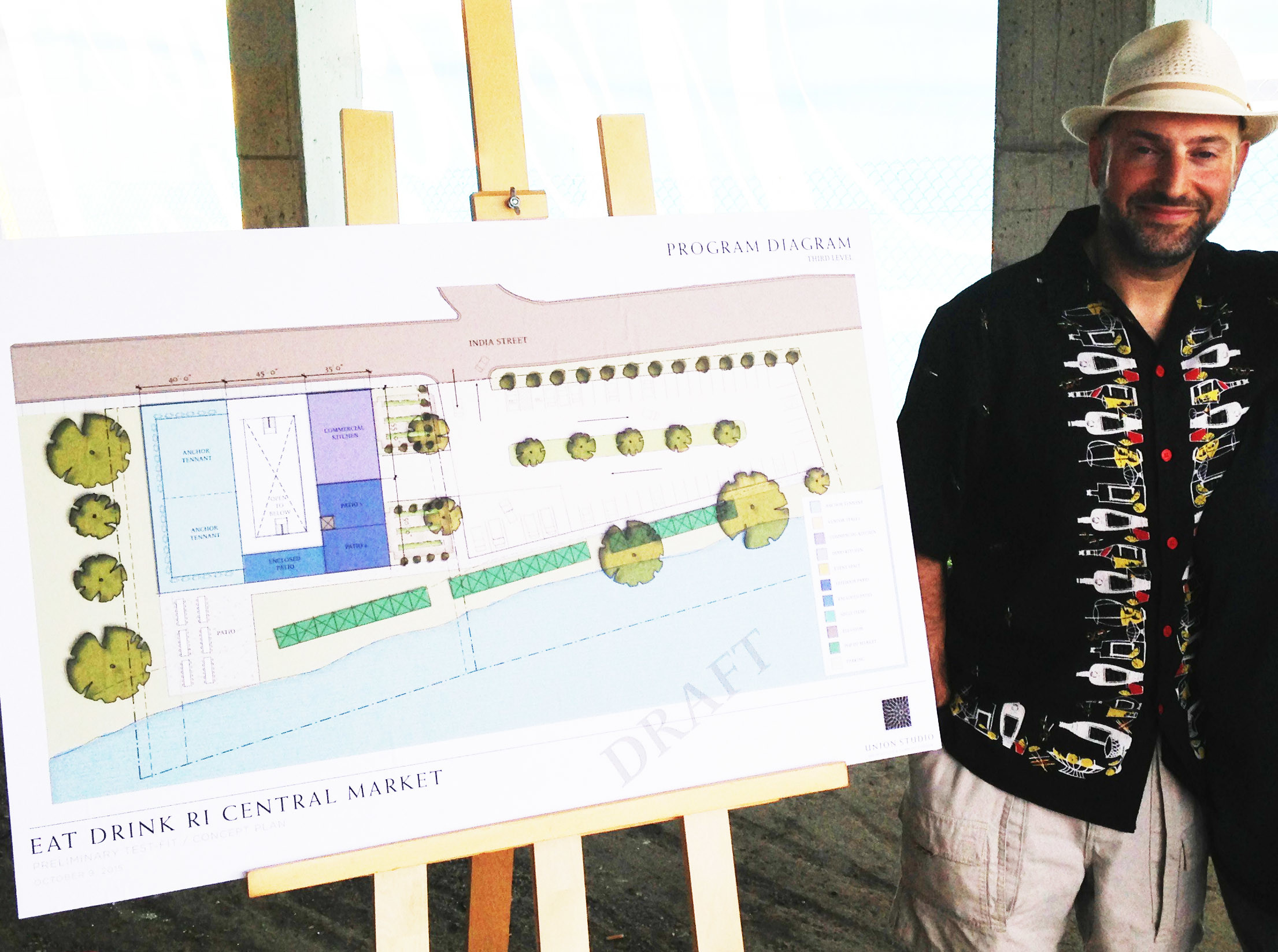

If all goes well with the proposed Rhode Island Central Market, an effort being championed by Eat Drink RI under the leadership of David Dadekian, it will become a food hub on the Providence waterfront, serving locals and tourists alike, promoting Rhode Island-based food products.

The state has hired its first food policy czarina, Sue AnderBois, to produce Rhode Island’s first food strategic plan, as a way to harness the economic development potential of the food industry sector as a key cluster in the state’s future economic development growth strategy.

Thanks in large part to the advocacy efforts of the Rhode Island Food Policy Council, AnderBois’s task will be supported by a new comprehensive analysis that creates a factual baseline for the food industry sector from 2011 to 2016, focused on public health, economic development and farming, identifying gaps and opportunities to leverage. The title of the report, the “Rhode Island Food System,” underscored the attempt to reposition the food sector as if it were occurring within a connected innovation ecosystem.

How all the different initiatives and assets will actually fit together and connect within the strategic plan that seeks to take flight as a commercial entrepreneurial approach is not yet clear.

Translated, what are the metrics for determining return on investment, within a systems approach to farmland, water, employment and sustainability? Those metrics may or may not fit very well within the established, traditional parameters that have been used to measure the return-on-investment in a commercial real estate deal or in an equity investment in a startup or early stage firm?

Particularly when it comes to the value of public health benefits connected to addressing neighborhood and community need, Rhode Island has some unique assets:

• From the neighborhood perspective, Rhode Island has the Sankofa Initiative, spearheaded by the West Elmwood Housing Development Corporation, and with it, a new platform to connect urban agriculture to affordable housing as a way to redefine the health and wealth of a community, what’s come to be known as health equity.

• From an urban farming perspective, Rhode Island has the Southside Community Land Trust, a champion of growing food in an environmentally sustainable ways to create community food systems, with goal of making locally produced, affordable, and healthy food available to all.

• And, it has, under the aegis of the R.I. Public Health Institute of Rhode Island, an innovative Food on the Move program to bring fresh produce to places such as senior centers in urban centers to help overcome food insecurity.

At the nexus of food and health

If we are what we eat, the statistics for bad health outcomes linked to diet-related chronic diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease, paint a dismal picture in Rhode Island.

Rhode Island, for instance, has the second-highest rate of obesity for children aged 2-4 years from low-come families in the nation, at 16.6 percent, according to the State of Rhode Island Obesity Report.

Providence and Kent counties have the highest rate of obesity [27.7 percent and 27.6 percent, respectively] and diagnosed cases of diabetes [9.4 percent and 9.5 percent, respectively. In 2012, based on research by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Rhode Island spent an estimated $663 million on preventable obesity-related care costs.

Not surprisingly, those bad health outcomes often fall disproportionately upon people of color in Rhode Island.

The solutions are not a mystery: better diet, more exercise, healthier housing, more affordable childcare, higher minimum wages, and better access to affordable health care.

And, the health benefits of following an extra virgin olive oil, plant-based diet are not a big secret: Mary Flynn, a local nutritionist at Miriam Hospital, has developed such a diet that has been shown to improve current health outcomes and decrease the risk of future chronic disease, achieving reductions in weight by patients and in better management of diabetes and heart disease.

A recent study published in 2016, co-authored by Flynn and Andrew Schiff, director of the Rhode Island Food Bank, found that an olive-oil, plant-based, seven-day meal plan, focused on serving the needs of low-income residents, produced substantial savings, when compared to an economical version of MyPlate, a seven-day meal plan that followed U.S. dietary guidelines.

What ain’t we got? An organized network of commercial kitchens open to the community that can bring the proven public health benefits of an olive oil, plant-based diet to a broader population through cooking classes, according to Flynn.

Translated, without a system of accessible community commercial kitchens, what’s missing is the capability of transforming the public health benefits of healthier food into a healthier diet. It’s a huge disconnect.

Supply and demand

How many commercial kitchens were there in Rhode Island where cooking classes could be held to teach folks how to prepare healthier meals, including the olive oil, plant-based diet?

David Dadekian, the maestro behind Eat Drink RI, said that the information had proven elusive to pin down.

“As far as I know,” he said, responding questions from ConvergenceRI, “that isn’t a data point that we’ve been able to pin down yet, as many of the commercial [kitchen] spots out there are private [churches, granges, etc.], and the public ones are few and far between right now.”

That’s why, Dadekian continued, “We want to keep [a commercial kitchen] in our Central Market plans.”

Hope & Main

At the food incubator at Hope & Main in Warren, the first such space in Rhode Island, there is a commercial kitchen, available to rent by members and community residents, explained Hana Early, the incubator’s community outreach coordinator.

Much of the focus of the current classes being taught is on how to make food your business, the food incubator’s slogan.

The scheduled August classes include: a ServSafe Food Safety Management Certification class, learning how to produce a food product and bring it to the public in a safe and secure manner; knife skills, life skills, with chef Peter Kelley, a professor at Johnson & Wales; tacos and tequila with chef Maggie Mulvena, covering some of Mexico’s greatest dishes and drinks; pasta making 102; and summertime appetizers and cocktails.

Early said that Hope & Main was open to any new ideas, but folks need to come in for an informational meeting and present a written description of what they’d like to do and go over scheduling.

Many of the classes for members of the food incubator, Early continued, are focused on helping them with branding capabilities, such as the ability to penetrate the social media market.

Hope & Main has also hosted cooking classes for children, Early said.

40 Main St. in Woonsocket

Neighborworks Blackstone River Valley, a community development corporation serving Woonsocket, has built a 3,000 square foot “culinary incubator” with a top-of-the-line commercial kitchen at the 40 Main St. property, with plans to help spark some 25 new food businesses.

The mixed-use redevelopment project is a key component of its efforts to create a new hub of activity in Woonsocket’s downtown commercial district.

The commercial kitchen, in turn, was in response to community needs identified as part of Health Equity Zone survey, which found there was a lack of access to healthy food.

Open Kitchen

When ConvergenceRI asked the R.I. Department of Health for a list of possible commercial kitchens available to host community classes for residents to learn about how to cook with the olive-oil, plant-based diet recommended by Flynn, agency spokeswoman Andrea Bagnall Degos provided a link from Farm Fresh RI and its Open Kitchen program, listing the commercial kitchens that food entrepreneurs can rent for a fee, with program’s goal to provide transparency to the process of producing value-added foods in Rhode Island, with a focus on local food entrepreneurs.

Included at the top of list was Farm Fresh RI’s Harvest Kitchen, which offers co-packing services and processing of private label products.

Food as medicine, food as a step up

Lifespan, as part of its Community Training Center on Prairie Avenue, offers a free, six-week class to teach participants how to prepare affordable and nutritious meals in order to improve their diet, all on a limited budget, working with a kitchen space in the building, featuring Flynn's program.

Genesis Center, in turn, offers a 13-week hands-on course that prepares participants for a potential career in the food service industry. Last year, participants in the Genesis Center program held a cook-off at the Sankofa Market with recipes they developed.

The mighty Flynn

When Flynn first began to explore the ways in which better nutrition through an olive oil, plant-based diet could be become more accessible to low-income residents, she began working with the R.I. Free Clinic in 2004, at the suggestion of former First Lady Stephanie Chafee.

“The question was: can you get people to cook meals that are healthy and economic, using olive oil, not meat, and not feel hungry after a meal?” Flynn told ConvergenceRI in a recent interview.

The program proved to be very successful, and led to Flynn’s collaboration with the R.I. Food Bank, which also proved to be wildly successful, according to Flynn.

“My skill,” Flynn explained, “is in simplifying information [in the recipes.]

Flynn said that she is also big on using frozen produce and canned produce, not just fresh produce from farmers markets.

To further the advocacy of the olive oil, plant-based diet, Flynn would like to see a small network of commercial kitchens established in Rhode Island. In terms of cost, Flynn said that a commercial kitchen, something you might see at a food show, costs about $10,000.

She would also like to see the nutrition program expanded to more places, such as senior centers. “Seniors are very, very receptive to my program; they’re very easy to work with; they eat it all up,” Flynn said.

Her goal, Flynn continued, is to establish a program, with controls, strictly with a low-income focus, on diabetes, because “it is such an expensive disease to treat.”

In contrast, she continued, the recipes for a meal with four servings in her diet cost about $5 each.

Because her diet improves health outcomes and metrics for blood pressure and glucose monitoring, Flynn has taken to emailing the patients’ primary care physicians with the results, which has resulted in triggering interest from the doctors about enrolling more patients.

Expanding the program

If Flynn could a wave a magic wand, she said d that she would want to find more permanent funding sources and locations for classes.

Flynn currently uses Brown med school students and nursing students from Salve Regina to help administer the program.

Altogether, Flynn priced an expansion to four sites with commercial kitchens and the necessary plumbing at about $100,000, including additional salary support to administer the program.

Flynn said that she wanted to expand her efforts to work with the Providence Community Health Centers, with its facility adjacent to the Lifespan facility on Prairie Avenue. The biggest problem now is that is difficult to access the patients’ electronic health records, because of system incapability.

Flynn re-emphasized the importance of keeping things very simple, when asked about the potential of bringing in local chefs to assist in the program.

“All the recipes are really easy,” she said. “My recipes take less time than it takes to go out to eat.”

Flynn is a passionate advocate for her olive oil, plant-based diet. “I never turn down an opportunity to talk about it. I am always trying to find programs to collaborate with.”

Attention Sue AnderBois: Perhaps you could schedule a sit-down meeting with Flynn to explore how her diet can become an integral part of the state’s food strategic plan moving forward.