Lively talks on social enterprise in RI offer varied takes on economic policies

In a gathering at the Brown Faculty Club on March 3, CEOs, decision-makers and policy advocates shared their economic visions

PROVIDENCE – It was one of those events that are so much in vogue these days.

You know, a gathering of the business elite from various Rhode Island tribes to have a conversation, a collision, about the je ne sais quoi quality of Providence and how to capitalize upon it.

It was not so much a conversation as a series of quick, five minute talks, TED style, to be followed by drinks and mingling.

In this latest episode of we talk, you listen, the event was dubbed “Cocktails and Conversations: Celebrating Strategies for Our Local Economy,” and the featured presenters placed a heightened emphasis on the eco in ecosystem.

The host for the event was Main Street Resources, a “place-based” small private equity shop that is developing a $10-$15 million Rhode Island Impact Capital Fund.

The co-sponsors were The Providence Foundation, the Greater Providence Chamber of Commerce, and Eco-RI, an online environmental newsletter.

It was held on March 3 at the Brown University Faculty Club, and two of the speakers, R.I. Treasurer Seth Magaziner and Rep. David Cicilline, provided the cover of officialdom and Brown-dom. [Neither Magaziner or Cicilline stayed for the mingling part of the event that followed.] Lt. Gov. Daniel McKee also attended, offering brief remarks at the end of the program.

The timing seemed good for such an event, explained host Dan Levinson, the founder of Main Street Resources and Brown alum, in an email: “Given the recent release of the Brookings [Institute] report, the Hassenfeld interview, $7.5 million for Job Lot, Brown’s announcement of its new entrepreneurship program, the increasing growth in social enterprise and the design/creative economy – so much great material for elevating the discussion.”

It occurred under the cover of a big tent of ideas and strongly held opinions. On one end of the political spectrum was Justin Katz, the research director for the R.I. Center for Freedom & Prosperity. Katz shared his “optimistic” vision for the future of Rhode Island, which began with the prediction of a big market crash in May of 2016, with the state’s economy then plunging into deep recession, to be followed by a series of miracles: the first, according to Katz in his imaginary narrative, was that a single mother stumbles on a prayer group and it leads her toward a new way of thinking about life, and she marries the father of her second child. The second was that the R.I. General Assembly enacted education savings accounts, which enabled her to enroll her son not in a failing school, but in a Catholic school that the mother picked because she believed that a faith-based moral environment was best for her son’s future. [Katz’s talk was posted in its entirety on oceanstatecurrent.com]

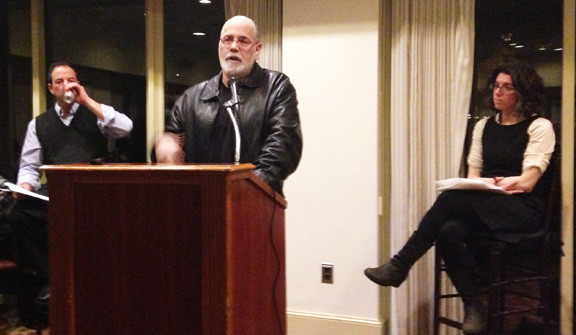

On the other end of the spectrum was Greg Gerritt, proud to be introduced as a forest gnome, offering a takedown of development for development’s sake. “What passes for growth is simply the financialization of the economy that is letting the 1 percent scoop up all of what is called growth while everyone else gets poorer, the ecosystems collapse, and the infrastructure fails,” he said. [Similarly, Gerritt’s talk was posted on RI Future.]

More to the middle of the spectrum were some of the usual suspects: Doug Hall from the Economic Progress Institute, who explained why the idea that “a rising tide lifts all boats” was full of holes; and David Huang, the newly anointed guru of economic development for the city of Providence, who promoted the promise of the food cluster and pitched the idea of creating a design center around aging as the innovation hub that he believed could remake Providence in the global market.

Then there were the muses of cultural and economic invention: Barnaby Evans of WaterFire, and Kelly Ramirez of the Social Enterprise Greenhouse. Evans spoke fervently about the scale of Providence and its history of innovation; Ramirez embraced the idea that nonprofits and for-profits were finding common ground around the values of social enterprise.

A number of social entrepreneur CEOs in the audience then gave quick elevator speeches about their products – including Nick Garrison from Foolproof Brewing, Deb Schimberg from Glee Gum, and Brenda Brock from Farm Aesthetics.

The closing comments were offered by Kenneth F. Payne, who chairs the Rhode Island Food Policy Council and administers the Rhode Island Agricultural Partnership, in an attempt to summarize what was said and what it meant.

A dose of intellectual Narcan

The range of presentations provided, in some ways, was a refreshing perspective compared to the narrowness of Gov. Gina Raimondo and her economic team leader, Stefan Pryor, in articulating and promoting Rhode Island’s economic future, as if their way was the only path to follow.

Call it a dose of intellectual Narcan administered to short-circuit the narcotic haze of repeating the mantra, “Make It in Rhode Island.”

[For the record, Magaziner, Cicilline and Huang all voiced support to some degree for the Governor’s plans in their presentations, as did Lt. Gov. McKee.]

And yet, despite the broadness of the ideas expressed, there was a different kind of narrowness of vision that afflicted the event, one that was recognized in part at the get-go by Levinson, and to his credit, said: “We would like to apologize for the lack of diversity [in the presenters]. I promise, it will be different [at the next event].”

That narrowness also surfaced in the aftermath of the presentations, during the mingling – call it smugness, mixed with an air of self-congratulation. While some of the presenters were willing to engage, others appeared diffident, not really interested in listening to what those in the audience had to say.

For instance, when a member of the audience approached Levinson to introduce him to someone who could help him with diversity, and began to talk about the Sankofa Initiative, Levinson cut short the exchange, asking for a business card and then quickly turned away. [To quote the line from the movie, “Cool Hand Luke,” “What we have here is a failure to communicate.”]

[It made ConvergenceRI think about Dr. Doug Eby’s instructions to his primary care providers about the need to learn to listen in 10 different ways.]

Another audience member pointed out that, at the end of the event, there had been a missing question. No one had asked: who was missing from the conversation? Good question.

Beyond exclusiveness

ConvergenceRI had been invited to attend by one of the evening’s presenters, but upon arrival, he was questioned as if he were a gatecrasher by one of the event’s organizers, who asked him pointedly: What are you doing here? How did you hear about this?

ConvergenceRI responded, trying hard not to be over sensitive: “Am I being asked to leave? Am I not welcome here?”

Not at all, the organizer responded. Still, it made ConvergenceRI feel a bit unwelcome, as if he had stumbled onto a meeting of an elite club of entrepreneurs and that no one had shared with him the secret handshake.

What was said, however, was worth sharing with a broader, more inclusive audience – to all those who had not been invited to attend the event at the Brown Faculty Club. In the interest of promoting convergence, here is a detailed synopsis.

Magaziner

Levinson introduced Magaziner not just as the state treasurer but as someone who was becoming a “state treasure.” Flattery will get you everywhere.

“One of the most basic concepts in the business world is the cost-quality curve,” Magaziner said. “You all know this. When you’re in business, and you’re producing a good or a service, you can either be at the two ends of the cost-quality curve – cheaper goods and services that are maybe lower quality but are more affordable for a wider range of people, or you can be toward the top of the cost-quality curve, which is a place where you producing more sophisticated, value-added products that sell at a premium in the market.

Magaziner continued: “The way I look at [economic development] in Rhode Island, and in the New England region generally, the story economically is about our attempt to crawl our way up the cost-quality curve.”

“We were once a low-cost manufacturing based economy; those jobs inevitably moved to where they were cheaper, overseas,” he said. “Now, following the lead of Massachusetts and others, we are fighting our way up the curve, to produce more value-added, high-quality business goods and services.”

The way you do that, Magaziner said, “is to invest in your knowledge economy, your infrastructure, your education, your institutions of higher learning, because at the end of the day, we cannot out-cheap the Third World, but we can out-compete the entire world by our talent.”

Cicilline

Ciclline spoke in his well-honed, rapid-fire delivery, saying that there had been too much focus on how you lure the next big company, the next big thing to Rhode Island. “That’s not the best way to do economic development,” the Congressman said. “Eighty-seven percent of the new jobs that were created in the last 15 years came from startups or existing businesses in Rhode Island.”

Cicilline continued: “I think what we need to be focused on is what we can do to create an environment to encourage startups, and to help to grow and encourage the startups that exist.”

The focus shouldn’t be on the issue of taxes, but rather the quality of the workforce and the quality of life. “Economic development is really about how you create cities and places that talent wants to live in.”

To start the revolution in [economic development in Rhode Island], Cicilline continued, “I think about three things: talent and workforce; access to capital in traditional and non-traditional, creative ways; and simplifying the regulatory framework for starting a business here.”

Cicilline concluded: “To create something new, that’s where the job growth is; it’s not simple. It’s not about bringing in a big company, if we want sustainable, economic growth and stability.”

Huang

A former venture capital investor from San Francisco, now in charge of economic development for the city of Providence, Mark Huang is a relative newcomer, having been in Rhode Island for eight months. He described economic development as a “four-legged stool.”

The first leg was incentives – something he said that both the Governor and the city were focused upon. The second leg was investments in your workforce and the economy of the future. The third leg was reform of the regulatory process. “I don’t think there’s anyone in this room who wouldn’t say that our regulatory process doesn’t have room for improvement,” Huang said. “It’s kind of like changing a flat tire while your car is still forward.”

The fourth leg is to think a little more strategically, looking at other case studies, such as Pittsburgh, Huang continued, focused on private-public partnerships.

Huang called for expanding the concept of “greater Providence” to include Rhode Island’s urban core. “If you define it that way, it’s over a half a million people, one half of the state.”

In his strategic direction, Huang said he was asking three questions: what is happening in the global economy, what are greater Providence’s core competencies, and can you draw a straight line to connect the global economy with Providence’s core competencies.

In doing so, Huang continued, “Providence can create a new economy that we can own, not borrow.”

The emerging food industry cluster was one of the lines that could connect the global economy with the city’s core competencies, according to Huang.

“The food industry is changing drastically. People are asking, where does it from and how is it made. [The market for] organically grown food is growing by 11 percent a year,” he said. With Johnson & Wales, with the state’s food culture, Huang argued that the potential was there to create a food distribution network. Huang talked about the large venture capital investments being made in food and technology.

A second core competency was what Huang called “the blue economy,” which he described as “anything to do with water, sustainability, oceanography and fisheries.”

As a strategy for economic success, he continued, was this: “We don’t just tell it to ourselves, we need to tell it to the world.”

A third core competency, related to the industry sub-sectors of health and wellness, was to capture technology advances that focused on aging and put it together into a design center, to be located on the former Route 195 land, and then tell the world. “Food designed for an 85-year-old,” he suggested, as a way to bridge the disparate sectors.

The redevelopment the former I-195 corridor is “a once in a lifetime opportunity for us.” [It’s a phrase that former Gov. Lincoln Chafee often invoked.]

“We should double down and triple down at what we’re good at, and we should own the spaces in those four areas,” he concluded.

Hall

Doug Hall, the director of Economic and Fiscal Policy at the R.I. Economic Progress Institute, attempted to reframe the discussion of economic development something different than “a means to maximize profits and serve the interests of the wealthy.”

Instead, Hall said the goal should be “to maximize the quality of life enjoyed by all the people in Rhode Island, to ensure that we meet the needs of the citizenry.”

Alluding to the opening remarks about the lack of diversity by Levinson, Hall said: “Just like Dan Levinson said he would have to be intentional and deliberate about making this room more diverse,” the effort to closing the gaps across a wide range of socio-economic indicators in Rhode Island “will not happen without an intentional commitment to do so.”

The free market, Hall continued, “will not look out for us.”

“We need to build an economy that places a premium on improving the lives of working families in Rhode Island, and in doing so, we need to be intentional, so that we don’t leave anyone behind, because of their gender, or because of their race and ethnicity,” he said.

Regardless of how fond someone was of maritime analogies, he continued, “It’s demonstratively untrue that a rising tide lifts all boats.” For a boat riddled with holes, there was not much a rising tide could do, other than sink it, Hall said.

And, while there are encouraging signs, Hall said, that the current administration recognizes that, “Simply repeating the mantra that everyone should make it in Rhode Island is not nearly enough.”

In building an economy that works for all and that results in shared prosperity, Hall concluded, “We need a set of policies that lift up Rhode Island workers,” calling for further expansion of the state’s earned income tax credit, increasing the state’s minimum wage, and increasing supports for child care.

Hall urged the importance of promoting the local economy by buying local. He also stressed the importance of protecting the environment, to protect the air that our children were breathing.

Gerritt

Levinson introduced Greg Gerritt by saying that the things he really knew “came from nature,” praising Gerritt’s willingness to walk the talk.

Gerritt, in turn, attempted to provide a different kind of context for the discussions around economic development. “It is time for those working in economic development to understand the new environment better and to prepare plans that match its opportunities rather than repeat the old stories,” he said. “Don’t try to spin the growth machine faster, that makes it worse for most of us. We must adapt Rhode Island’s economic development to the low growth environment and work to create a more widespread prosperity through reviving ecosystems and economic justice.”

For Gerritt, the first step is accepting the fact that economic growth is “dead in the old mill towns of the industrialized West, and it is never coming back.” There will still be economic growth in the tropics and Asia, the places [where] there are still “untapped natural resources and indigenous communities to plunder,” with the cities swelling with people streaming out of the countryside.

The World Bank, Gerritt continued, said that keeping the forest in the hands of the forest people, and assets in the hands of the poor, create better outcomes than any other strategy for development and, he added, “may be the only chance we have to stop climate change.”

Gerritt argued that economies needed to be built from the bottom up, not the top down. He also called for a more holistic approach to improving the health of communities: reducing pollution, reducing harms, and good nutrition. “It is absolutely impossible to have affordable health care for all if you use the medical industrial complex to drive economic growth,” he said. “When the health care industry grows faster than our wages, the industry draws investment while most of us still cannot afford to go to the doctor.”

Gerritt urged that that people “pay attention to the resistance.”

“We can live in Flint, we can live in Ferguson, or we can have prosperous communities that heal ecosystems and practice justice,” he concluded. “It’s your choice.”

Katz

Justin Katz, the research director for the R.I. Center for Freedom & Prosperity, offered a parable of the future as his presentation, which began by imagining that an economic crash would take place in the near future, which in turn would create the opportunities for a different kind of community to emerge, one driven by faith and self-determination and not government.

Two months from today, in May, Katz began, “The stock market crashes, and all the artificial mechanisms of this economy fall apart, plunging the U.S. into a recession at least as deep as the last one.”

Katz then sketched a story about a family in a public housing development in Providence, a single mother with a four-year-old son, along with single mom’s mother, also a single mom, celebrating the child’s birthday, and blowing out the candles in two tries.

A series of “miracles,” according to Katz, then occurred, beginning with participation in a prayer group, the marriage to the father of the child, the son’s admission to a Catholic school through education savings accounts, the start of a small business, and the ability to buy a home.

“They take a chance and invest in their new idea,” Katz said in his narrative, “because the state has stopped trying to define innovation. At this point, Rhode Island is no longer one of the worst places in the country to start a business, and [the family] is staying, despite their success.”

To set the story in motion, Katz concluded, Rhode Islanders needed to have the courage to define the future by not having the state define the lives of everyone who is living here.

Ramirez

Kelly Ramirez, the CEO of the Social Enterprise Greenhouse, offered her perspective about the importance of finding the common ground between government, nonprofits, and the private sector.

In her view, the world is moving toward the middle: government is increasingly outsourcing social services to community-based organizations that have proven solutions.

To accomplish this, Ramirez continued, there has been the development of social impact bonds and investing, leveraging private sector dollars to invest in proven social impact interventions, with better outcomes and cost savings to taxpayers.

Ramirez praised both Magaziner and Cicilline for their efforts to support such social enterprise investments: Magaziner for his idea that Rhode Island could emerge as the “Delaware” for social benefit corporations, and Cicilline for his introduction of the first piece of federal legislation to support social enterprise development, with bipartisan support.

“I would argue that Mark [Huang] is actually a social entrepreneur,” Ramirez said, “bringing private sector innovations to municipal government.”

In Ramirez’s view of the future economic development world, the fulcrum is shifting: instead of the nonprofits at one end of the spectrum, creating social impact, and business at the other end of the spectrum, maximizing profits, a new reality is emerging.

“Why is this?” Ramirez asked rhetorically. “Because, businesses are realizing that by adopting socially responsible strategies, they are actually maximizing their bottom line.”

Ramirez cited the experience of Whirlpool, which donated appliances to all Habitat for Humanity homes built in North America, and encouraged their employees to go out and help build these homes. As a result of this partnership, Ramirez said, “Profitability skyrocketed, because their employees felt purpose, and they were motivated.”

Her favorite story, a local story, was about a family owned small plastics company that got taken over by the son, Michael Brown, who was a “big environmentalist.”

The company now creates a 100 percent recycled plastics products, such as trays to be used as food containers, which she said would hopefully begin to be used at Whole Foods markets very soon.

“Michael got involved with the Social Enterprise Greenhouse as a volunteer,” she said. “He then organized his business to become Rhode Island’s first [social] benefit corporation.”

There are now some 1,619 such corporations in the U.S., Ramirez said. Brown, in turn, she continued, directly attributed the very rapid growth of his company to becoming a social impact company, because other companies wanted to work with him.

Evans

Barnaby Evans, the creator and maestro of WaterFire, talked about the importance of scale in Providence, which allowed for really innovative things to happen.

“I did WaterFire because I watched this amazing civic project, the uncovering of rivers and the rebuilding of spaces downtown, completely fail to [attract] anyone to come to the place,” Evans explained. “I wondered whether one could be bold and innovative and try something new to re-brand the city from a place of failure and depression.”

In Evans’ view, WaterFire was Philanthropy 0.0. “We have to feel good about where we live before we can engage in doing it,” he explained.

Evans continued: “I’m fascinated by the great number of people who dig in and want to work at changing [Providence for the better]. Part of the Kool-Aid is the scale of the city, to realize that there’s enough interactive friction that you can have an impact, and WaterFire is a good example – it brought some $2 billion in spending that came to the state that otherwise wasn’t coming here.”

The success of WaterFire, Evans said, was in its ability to make an emotional connection to people. “It’s about empathy and engagement, spirituality, aesthetics and beauty; it’s about spectacle, freedom, and doing things at a city scale.”

Evans cited the network of 700 volunteers, and the really tight connection to the audience, and the fact that the audience seems willing to roll with all sorts of different kinds of metaphorical space we create, where possibility and surprise can happen all the time. “I do think that Providence has great potential,” Evans said. “Quality of life is the 21st century [calling] card and we have it in spades. We need to be proud about it and continue to develop that place.

In terms of future projects that might become part of WaterFire, Evans talked about his desire to have Providence reclaim its place as the seat of American innovation.

“Roger Williams, the founding of this state, is an amazing story,” he said. “The whole idea of freedom and separation of church and state, free speech, freedom of thought, the quality of life. It was the only government in the history of the human race that was founded [on these ideals], and it was founded here, and it became the bedrock of the American vision.”

Evans also said that the robotics revolution started in Providence, with the development of the Brown and Sharpe milling machine, the first tool made that was used to make itself.

Perhaps the biggest addition to WaterFire that Evans is considering is the possibility of creating a full-scale replica of the Gaspee and then burning it, as a spectacle.

“The burning of the Gaspee was where the American revolution started,” Evans said. “We want to work with high tech high school students to create a full-scale Gaspee that we can burn every June, to celebrate in a big, 21st-century way, to show that we actually did start the fire.”

Finally, Evans said that one of the challenges of the current economic model is that there are a lot of externalities that are not captured in the equation. “The social enterprise model is fantastic; we love it, we live in it,” Evans explained. But, he continued, there are larger, community wide models that we need to look at, such as water quality and environmental considerations.

Evans said WaterFire has been nurturing the Woonasquatucket River Greenway Project, envisioning a full-scale pathway connecting downtown with Olneyville, facilitating a two-way pattern of pedestrian and bike traffic.