Warning: ignoring lead poisoning may be harmful to your political future

This year’s Childhood Lead Action Project annual celebration puts the focus on what has happened in Flint, Michigan

PROVIDENCE – What was not asked about or discussed during the 2016 Presidential debates is perhaps as important as what was discussed: there were no questions about climate change; there were no questions about the rising toll of overdose deaths from opioid drugs, and there were no questions about the lead poisoning disaster of the entire city, Flint, Mich., because of man-made decisions about how to save money in the budget.

The reality of climate change is not going away. Neither is the epidemic in drug overdose deaths.

And, the story of lead poisoning in Flint and elsewhere in America is not going away. Neither are the questions about corporate liability and racial disparities.

In the Oct. 23 edition of The Washington Post, in a story written by reporter Brady Dennis, the headline reads: “In Flint, a water crisis with no end in sight.” [See link to story below.]

The story begins: Even now, the people of Flint, Mich., cannot trust what flows from their taps.

More than one year after government officials finally acknowledged that an entire city’s water system was contaminated by lead, many residents still rely on bottled water for drinking, cooking and bathing. Parents still worry about their kids. Promised aid has yet to arrive. In many ways large and small, the crisis continues to shape daily life.

From the pulpit some Sunday mornings, the Rev. Rigel Dawson [who leads the North Central Church of Christ in Flint], can see it.

The anger and frustration over Flint’s contaminated water, so visceral at first, over time has given way to something almost worse: resignation.

The story continued: “It was one more big thing on top of a bunch of things,” Dawson says.

You have to understand, the pastor says, that people in Flint are resilient. They’ve endured crime, blight, decades of economic hardship. But as the water disaster stretches on, it has chipped away at the usual stoicism of his parishioners at North Central Church of Christ.

“You can see the pain it’s caused. You see the discouragement and frustration,” says Dawson, whose own children still must bathe in bottle water. “Members are enraged, depressed, despondent, hopeless. You see the full gamut of emotions.”

When President Obama came to town in May, the 40-year-old Dawson was among the Flint residents [whom the President] met with privately. [Dawson] tried to explain how marginalized people feel, how certain they are that, had this happened in a more affluent community, change would have come sooner.

“I told Obama: ‘It makes you feel like you don’t count… People sometimes feel that we don’t really matter. We’ve had to fight and wait, fight and wait, for things that should have happened but haven’t.”

The story continued: Later that day, on stage at Northwestern High School, Obama referred to the conversation. “I think it was a pastor who told me: ‘You know, it made us feel like we didn’t count,’” the President said. “And you can’t have a democracy where people feel like they don’t count, where people feel like they’re not heard.”

Bringing Flint to Rhode Island

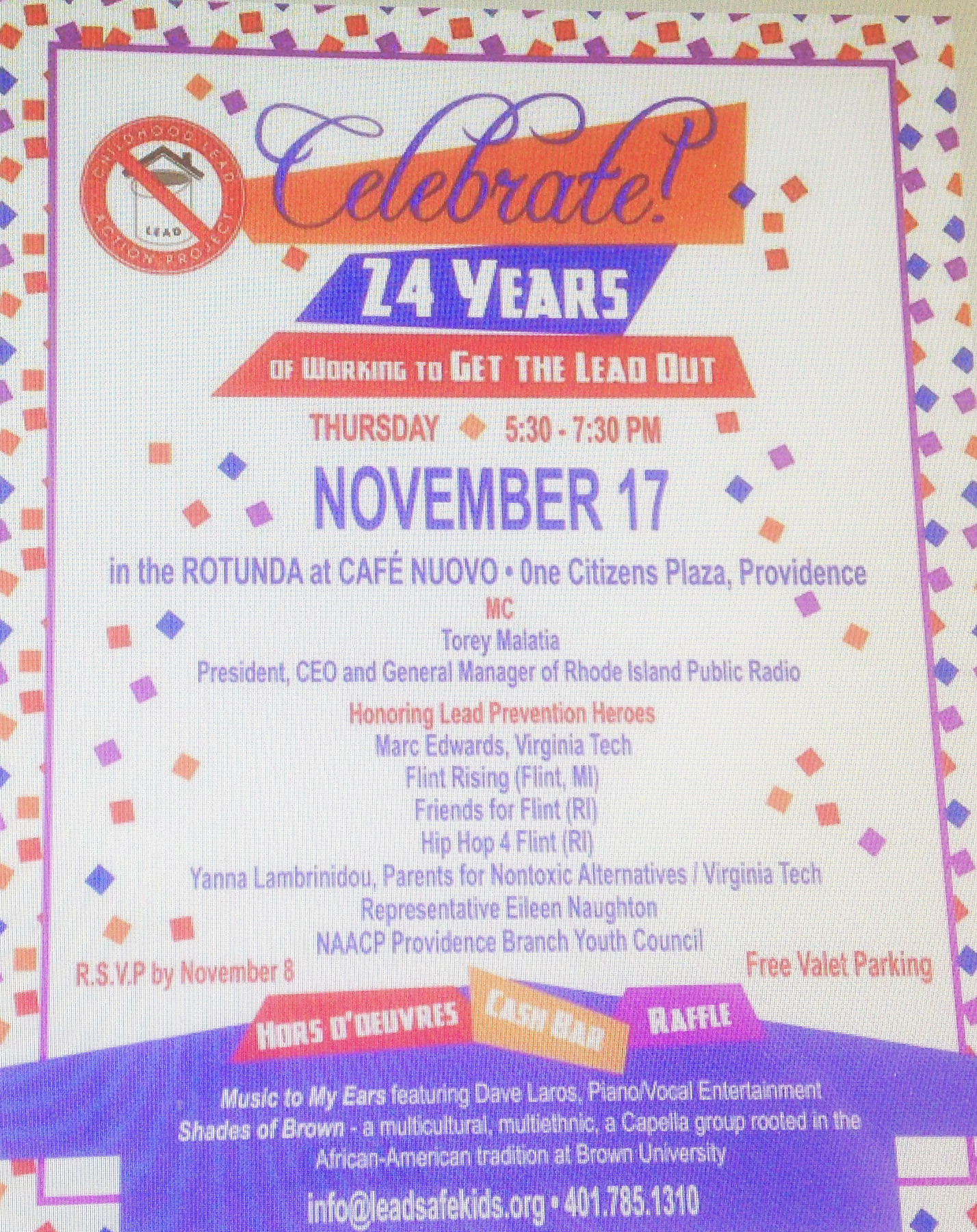

Here in Rhode Island, the 24th annual celebration of the Childhood Lead Action Project on Nov. 17 will very much have Flint, Mich., as its focus. This year’s honorees include: Marc Edwards, the professor from Virginia Tech who helped identify the source of the problem in Flint; Flint Rising, a community action group from Flint; Friends for Flint, a Rhode Island-based group; Hip Hop 4 Flint, a Rhode Island-based group; Yanna Lambrinidou, head of the Parents for Nontoxic Alternatives at Virginia Tech; Rep. Eileen Naughton; and the NAACP Providence Branch Youth Council.

The reality of lead poisoning, however, is that it is not a just a problem happening far away: in Rhode Island, nearly 1,000 children are newly poisoning with elevated levels of lead in their blood every year, bringing with it the promise of a potential lifetime of diminished health, education and economic consequences. The lead poisoning of Rhode Island’s children is creating a permanent underclass, reinforcing racial disparities in educational and health outcomes.

As much as there have been improvements over the last decade in decreasing the number of children who are being poisoned by lead – a fact often championed by Rhode Island elected officials and community advocates – perhaps the biggest challenge to the growth of the workforce to meet the demand of the state’s innovation economy remains the chronic, long-term challenges of adults who have been poisoned by lead as children.

If you want to improve reading test scores for third graders in Rhode Island, for instance, one of the best strategies would be to get rid of the lead that is poisoning the state’s children, according to a recent study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, focused on education outcomes for Rhode Island children who had been poisoned by lead.

The study was written by Anna Aizer, a professor of Economics at Brown University in the Population Studies and Training Center department; Janet Currie, a professor of Economics and Public Affairs and director of the Center for Health and Well-Being at Princeton University, Dr. Peter Simon, an associate clinical professor in Pediatrics and Epidemiology at Brown University, and Dr. Patrick Vivier, an associate professor of Community Health and Pediatrics at Brown University, a pediatrician affiliated with Hasbro Children’s Hospital, and a member of the executive committee of the new Hassenfeld Child Health Innovation Institute.

The study constructed an individual-level longitudinal dataset that linked preschool blood lead levels with third-grade test scores for eight birth cohorts of Rhode Island children born between 1997 and 2005. It found that decreases in average blood lead levels reduced the probability of below proficient reading skills.

“Poor and minority children are more likely to be exposed to lead, suggesting that lead poisoning may be one of the causes of continuing gaps in test scores between disadvantaged and other children,” the study concluded.

Translated, if you want to improve test score performances in Rhode Island, the priority should be to invest in removing lead from the environment – from substandard, poorly maintained older housing, from drinking water, and from the soil.

The study has earned national attention: it was featured by New York Times columnist Paul Krugman in his Sept. 2 column. It was also the subject of a Washington Post wonkblog, entitled: “Researchers have found a cheap, easy trick that really helps poor kids learn to read.” The answer: prevent children from being poisoned by lead.

Cognitive dissonance

However, leaders in Rhode Island, including Gov. Gina Raimondo and K-12 Educational Commissioner Ken Wagner, when asked by co-author Peter Simon at a Sept. 14 photo op and cheerleading event for the Governor’s new initiative to improve third-grade reading scores in Rhode Island by 2025, said that they had never heard of the study, nor had they read it.

They did nod their heads and say yes, promising [placating or patronizing may be a more apt word choice] Simon that they would read the study. To date, however, no one has followed up with him, Simon told ConvergenceRI on Oct. 23.

Responsibility and liability

Since it began publishing in September of 2013, ConvergenceRI has covered the man-made plague of lead poisoning extensively, making it a priority, posting dozens of stories. So far, in 2016, there have been 12 stories published, focused on lead poisoning and other forms of environmental toxins.

The tragic story of lead poisoning is one that very much connects and converges around health, science, innovation, technology, research and community in Rhode Island’s innovation ecosystem, even if the coverage does not always conform to what some elected officials and community groups may want to promote.

To paraphrase Hillel: “If I am not willing to tell the story, who will tell it? If not now, when?

When the man-made disaster struck Flint, caused by budget austerity decisions made by state government managers, it was the community that came to the rescue, as is often the case in threats from environmental toxins that poison children and families.

But to succeed, it takes resources: communities need to work in collaborative fashion, in partnerships with businesses, agencies and elected officials.

Changing those dynamics also includes the need to hold corporations and government officials accountable for their actions. Lost in the all the hoopla around GE’s decision to relocate its corporate headquarters to Boston and locate part of its new digital division in Providence, with the promise of good, high-paying jobs, is the legacy of its PCB pollution in Pittsfield and its fight to avoid the full responsibility for cleaning it up.

As detailed in the story by Clarence Fanto in The Berkshire Eagle on Oct. 18, the EPA upheld plans to remove PCBS from the Housatonic River and rejected GE objections. [See link to story below.]

The EPA plan would remove some 89 percent of the PCB contamination flowing over the dam at Woods Pond; GE wanted to save an additional $130 million by limiting that to 13 percent, according to the story.

The two sides also disagree on much PCB contamination remains in the river: GE said 70,000 pounds, the EPA put it at 600,000 pounds.