A conversation with the next Rachel Carson

An interview with research scientist and writer Rebecca Altman, an archivist telling the story of the evolution of plastics as a malignant force in our lives, encrypted within our blood and bone

Narragansett Bay, which defines life and commerce in Rhode Island, has achieved a remarkable restoration, in an effort led in large part by Save The Bay since 1970, and the investment in advanced sewage infrastructure by the Narragansett Bay Commission.

Narragansett Bay was once the home of the ports intimately involved with slavery, a reckoning with its past which is still taking place. Today, the port of Providence is home to huge fossil fuel infrastructure and a recycled metal export business, both of which challenge the future health of the Bay and the surrounding communities.

To change course, we need to create a more honest, accurate narrative that, like the sordid history of slavery, holds those industries and corporations accountable for their actions. To talk about the potential of the Blue Economy and leave out the threat of microplastics and PFOAs and PCBs is similar to the way that Fortune once attempted to tell the story of the nation’s corporate industrial behemoth using Ansel Adams’ photos – as exploitative, industrial pornography.

PROVIDENCE – Rebecca Altman has performed a brilliant synthesis in her writing, telling the story of how plastics have reshaped our economy, our chemistry, our bodies, and our lives in the last century.

If I were a scout for the MacArthur Foundation, searching out genius for their next round of grants, I would send them the latest chapter in Altman’s storytelling, “Upriver,” published in Orion Magazine, as profound a work as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. The prose is haunting and compelling. [See link below to “Upriver.”]

Odetta once told me the story, in an interview I conducted with her in 1972, how Charles Mingus, after listening to her sing, “Black Woman,” a combination field holler, a moan and blues, at a Duke Ellington Fellowship Award ceremony, came backstage to tell her: “Thank you for introducing me to myself.”

That’s how I felt after reading “Upriver.” Altman has introduced me to myself, and in a broader context, our lives to all of us. Thank you.

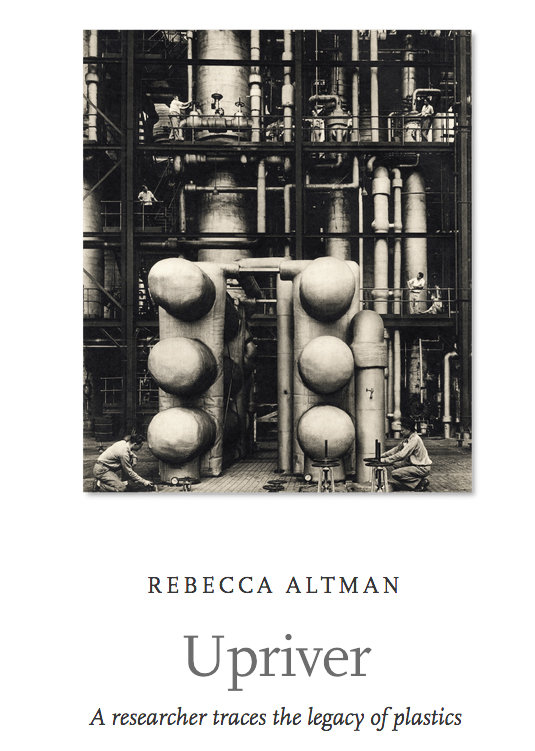

To illustrate the story, Altman used Ansel Adams’ photographs [with permission of the trust overseeing Adams’ work]. Originally published in Fortune magazine, the images projected a vision of American industrial strength and corporate might, the triumph of machines over men and women.

What had been left out of the Fortune photo essay was the workers’ story, many of whom had perished in the toil to create the industrial behemoth of what was then known as Carbide. Altman stitched the workers’ story back into the narrative, as well as her own personal story, creating a revelatory landscape, one in which we all reside, one that we need to recognize.

“Upriver” is the latest chapter of a work in progress, The Song of Styrene: An Intimate History of Plastics, to be published by Scribner Books. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “What’s entangled and enmeshed in the plastics is us.”

As a nation, we are currently engaged in a fierce dialogue about how we teach American history, reflective of our sordid relationship with slavery and racism. “Upriver” captures our current history as we enter the plastisphere in the Anthropocene era, where plastic artifacts keep washing up on our beaches – whether it is millions of Legos lost at sea near Cornwall two decades ago, or tons of microplastic pellets from a burning ship off Sri Lanka two weeks ago.

Altman’s narrative, much like Rachel Carson did nearly six decades ago, captures so much of what has been missing from our history books and from our politics. Here is the latest ConvergenceRI interview with Rebecca Altman, Ph.D., writer and environmental sociologist, a Rhode Island treasure.

ConvergenceRI: Why did you begin with poet Muriel Rukeyser’s Book of the Dead and her haunting phrase, “A corporation is a body without a soul,” and the story of the dry-tunneling through Gauley Mountain?

ALTMAN: Union Carbide is synonymous with the Bhopal disaster in the 1980s, the legacy of which is still unfolding. But Carbide’s corporate life is book-ended by another disaster, though I worry what happened at Hawk’s Nest is unknown, receding from collective memory, or in any case, their histories recorded as if [they were] discrete, rather than interconnected events.

What do pesticides have to do with a hydroelectric dam built to power ferroalloy furnaces, and in turn with plastics? In between those industrial tragedies, Carbide affected other communities, which is part of the work I’m doing, me being the daughter of a former Carbide engineer who made plastics for the company in New Jersey.

I felt a kindred connection to Rukeyser. Like me, she was trying to understand the legacy of Union Carbide. But she also was an outsider to the region. An outsider, but with her own familial connection to industrial enterprises that inform her sensibility, her ethics – the work of art [serving] as witness.

Structurally, I also wanted to begin the story upriver. To begin to identify the source waters for the pollution and plastics and related problems that followed.

But also, upriver in the metaphorical sense of Union Carbide’s pre-history. Before it moved into chemicals and plastics, the company was in metals and welding tools and related technologies. Carbide resulted from the merger of five companies that worked in ferroalloys, the electric arc furnace, and related technologies [electric arc furnace’s carbon electrodes, calcium carbide, also made in such a furnace, and acetylene gas in turn made from calcium carbide and used, for example, in metal welding tools.]

But it let me begin the story upriver from the South Charleston, West Virginia, Carbide plant, where full-scale, integrated petrochemical production was initiated in a significant way.

There is a parable in public health, best narrated by the biologist Sandra Steingraber, one that I describe in the piece, about going upstream to address the source of problems to relieve the work of triage and treatment downriver.

That parable had meant a lot to me. But, in laying out the events in this essay, I realized it was more than a parable, it was a method. In the story, I travel up two other interconnected rivers to explore other facets of petrochemical and plastics’ beginnings.

Let me also add that: At the outset, I had three themes I wanted to explore, to weave into a story. One was to mark the centennial of Carbide’s work to integrate petroleum and natural gas with chemical production, at the time [late 1910s and early 1920s] still very much reliant on the coal/aromatic chemistry as well as salt/brine and wood chemistry.

But I also wanted to explore plastics’ contingent beginnings. To move plastic narratives away from mythologizing the firsts, the founders, the fathers, and the flash-in-the-pan origin stories.

Lastly, I wanted to explore the way plastics were dependent on other technologies: in metals, for example, and in additives, what I’ve taken to calling plastics helpmate chemistries like plasticizers.

ConvergenceRI: You weave the story of your own research and personal story of your visit to Little Hocking, with your notebook and your tape recorder, to tell the story of what happens when: “Material culture and industrial infrastructure carry the history of their making. What happens when their residues enter the body?” Why is it so important to connect the personal stories of people to the chemistry and to the corporate structures?

ALTMAN: I spent my grad years at Brown [2002-2008] studying biological monitoring, the science of monitoring pollutants in bodies the way environmental scientists study them in any other media: sediment, soil, air, groundwater.

Interpreting the studies was often contested terrain, as exposure data, that is what was found in bodies, was often known before science understood fully how pollutants interacted with bodies’ physiological processes.

That is because of how industrial chemicals are regulated in the United States: innocent until proven otherwise, the exact opposite model of how drugs are regulated [where pre-market safety testing is required]. For many contaminants, there may even be an absence of good health and safety information in the public domain, which was the case in the 2000s, as PFOAs and PFASs, [had been] in use for over five decades, but [were] unregulated and so considered an emergent pollutant at the time. It was found in bodies years before science could parse what its presence might mean for human health.

I was trained as a social scientist to study the scientific contestation that followed biological monitoring in such instances. But eventually, my questions led me into industrial history. What does it mean that bodies harbor industrial chemicals?

I came to realize that to study body burden is to be an archivist, and that I had to learn to read those stories encrypted within blood and bone.

Even if science can offer little insight in what it might mean for an individual’s health, or even a collective’s, it nevertheless indicates something about this moment in time and the generations that preceded it. It means the past is present. And, with it, the priorities and policies of that past, too.

ConvergenceRI: If you had the opportunity to sit down with Attorney General Peter Neronha, who has called himself the state's public health advocate, what would you tell him and what would you ask him to do?

ALTMAN: In truth, I haven’t been in Rhode Island that long, and half my time here has been during COVID. I’m still trying to learn about public and environmental health and justice concerns here.

I’ve read addressing -- and preventing further -- PFAs in drinking water is a paramount issue, as with so many other states, and Rhode Island can’t act fast enough to lower human exposure immediately.

I’ve also been thinking a lot about the legacy of lead in the state – the legacy of lead in water pipes and house paint. For a child, for a developing brain, there is no safe level of exposure.

But I hope he’s attuned to communities, particularly those who live in and among the state’s existing fossil fuel infrastructure, especially near the Port of Providence, where the neighboring communities are already overburdened by emissions from the transit corridor, from the existing tanks, and concerned about the possible future expansion of LNG infrastructure, which would run counter the state’s recent climate legislation.

But fossil fuel infrastructure also includes proposals for so-called chemical or “advanced” recycling, waste pyrolysis, and plastics-to-energy syngas production, all of which are a downstream attempt to deal with disposable plastics overproduction that can generate further and even more complicated public health risks down the line.

I wrote a multi-page, footnoted letter to the DEM in regards to a medical waste pyrolysis facility proposed for West Warwick, which I understand he’s expressed concerns about, too, I’d be happy to share it with him if he’d find it of use.

ConvergenceRI: The inclusion of Ansel Adams’ photographs adds a graphic element to the story that is often missing from most environmental reporting: the images of the industrial behemoth, the images published by Fortune. Yet, as you report, Fortune remained silent on the silicosis disaster. Why is that?

ALTMAN: Fortune profiled Union Carbide in a three-part series that ran as the U.S. entered World War II. Ansel Adams was commissioned to photograph the company’s West Virginia petrochemical and ferroalloy plants in the third feature of the series.

But the text ran without a byline. It remains unclear who wrote the story. So I cannot rule out the degree to which Carbide influenced what made it into print. The text does suggest that Adams was one of the few outsiders to gain admittance into the plant, which struck me.

One must read this series within the larger context of the geopolitical moment. From the outset, coal tar and later petrochemical production were tied into nation-building and war-making and even posturing between nations.

Germany had been a chemical production powerhouse decades before the US. Carbide was portrayed as muscle, as an industrial behemoth, and was one of the key industries supplying industrial chemicals and related products to support the war effort.

Carbide, for example, along with DuPont, was unique at the time in that the U.S. government had arranged a special license for – and contracted with – to make polyethylene plastics, first developed by ICI in the UK. The capacity to produce it at scale was still very new at the time.

Also, I should note, the essayist Catherine Venable Moore, who has written extensively about Hawk’s Nest, and other scholars of the disaster, Carbide lobbied extensively for its interests in the wake of the tragedy, which meant keeping the story under lock and key. Actual lock and key. Moore describes documents locked in a storage closet within the bowels of the hydroelectric infrastructure.

ConvergenceRI: What is the best way to talk about material culture and industrial infrastructure in the 21st century?

ALTMAN: As contingent. As interconnected.

ConvergenceRI: You write: “To the industry, upstream is a place of surfacing, of unearthing long-sequenced hydrocarbons. It is derricks and pump jacks, inland fracking wells and offshore oil rigs,” as a way to introduce ethylene, what you describe as the photographer's light and shadow. What did you mean by that? Why is it important for people to understand the process?

ALTMAN: I wanted to create the image of the building blocks that industrial chemists work with to make molecules, polymers. Artists work with phonemes, with syllables. Photographers build images from light and shadow and shape.

Industrial chemists build plastics with benzene, with chlorine, and these days, especially with ethylene, for example. I once read a quote that ethylene is to the plastics maker as flour is to the baker.

If you think about just the commercial plastics identified by the iconic resin identification codes, the number-letters stamped onto the inverse of consumer plastics, either inside the chasing arrows of the recycling symbol or [more recently] an equilateral triangle, ethylene is used to make plastic No. 1 (PET), No. 2 (HDPE), No. 3 (PVC), No. 4 (LDPE), No. 6 (PS) and perhaps others within catch-all No. 7 category. [Plastic No. 5 is PP, based on propylene.]

And initially, I’d written in the line about the baker’s flour. But then I realized there was a better way to describe the process of synthesizing plastics that tied back to the work of building images, building poems, especially the way Rukeyser worked, the way Adams worked. All of it is an art of combination, juxtaposition, synthesis, I suppose.

ConvergenceRI: How persistent and prolific are PFOAs in our lives? What are the consequences?

ALTMAN: I wrote about this for Aeon in 2019. [See link below to the essay, “How 20th century synthetics altered the very fabric of us all.”]

ConvergenceRI: Have you even talked with or collaborated with Joseph Braun at Brown, who has conducted numerous studies on the impact of PFOAs on mothers and children as part of the huge study in Cincinnati? [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “Researching the relationship between toxic chemicals and bad health outcomes.”]

ALTMAN: No. I know of the project. But we haven’t spoken before.

ConvergenceRI: Have you gone out into Narragansett Bay to work scientists attempting to capture plastic "pollution" in our waters and fish? What did you observe?

ALTMAN: I am planning to shadow a URI grad student this summer who is doing microplastics work in and around the Bay – and I’m truly excited to watch, witness, and when I can be useful, help out.