A tale of collaboration in which Henri Termeer helped steer policy changes

A pivotal gathering in May of 2005 helped to create the trajectory of the life sciences industry cluster success in Massachusetts

BOSTON – On May 12, Henri A. Termeer, 71, the former chairman, president and CEO at Genzyme Corporation, died after collapsing at his home in Marblehead, Mass.

In the obituary published by The Boston Globe, the newspaper recounted numerous stories and tributes to Termeer, who was called the “dean of the biotech community” and a “true visionary.”

The obit recounted the rise of the company under Termeer’s leadership, beginning in 1983, from its warehouse near Boston’s Combat Zone, wryly dubbed by Termeer as “the most romantic of neighborhoods,” to the opening of its new corporate headquarters in Kendall Square, which The Globe described as “an anchor of Cambridge’s life sciences [industry] cluster,” and then, the purchase of Genzyme by Sanofi SA in 2011, a French Big Pharma giant, for more than $20 billion.

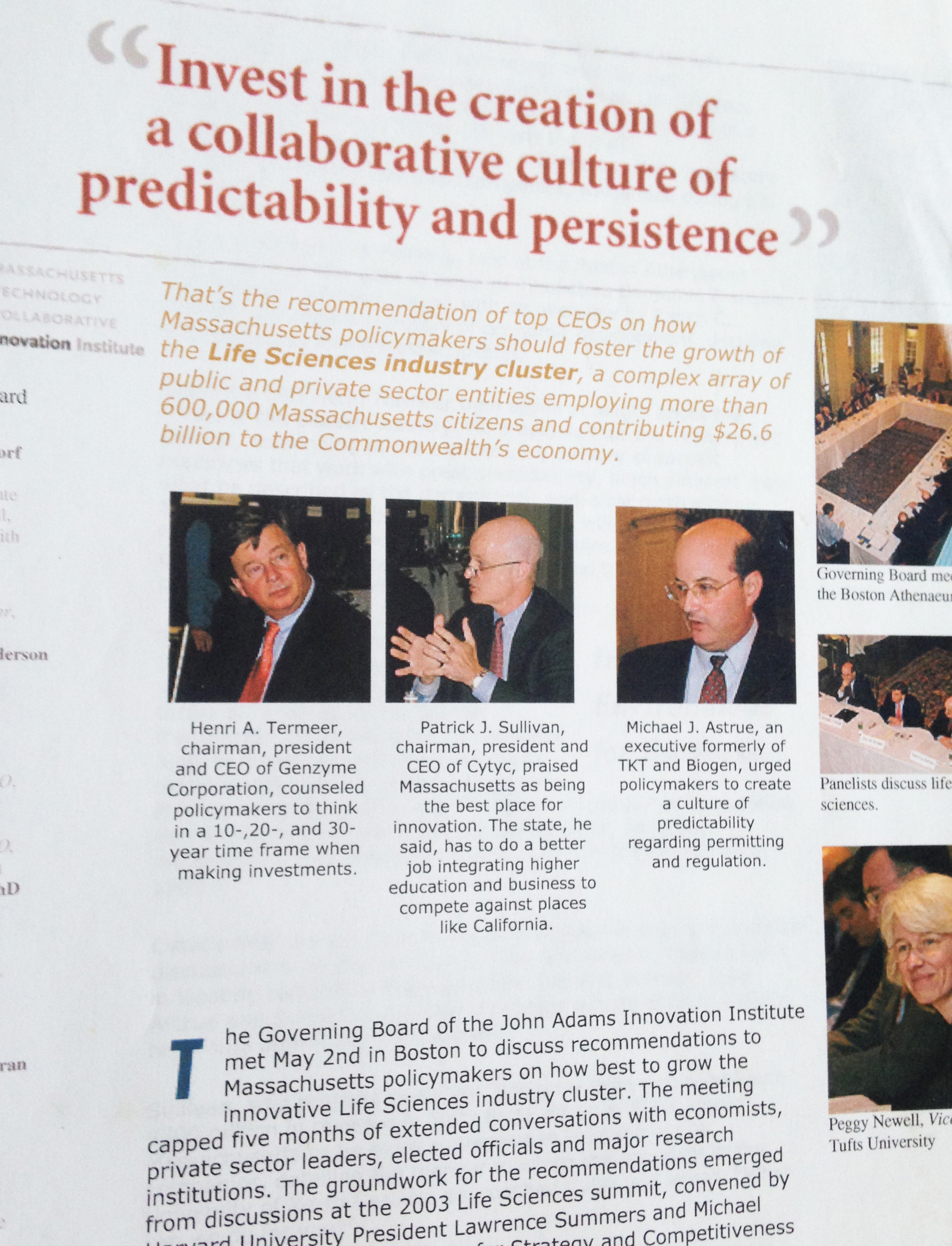

But one crucial story was missing from The Globe’s account, an event that occurred 12 years ago, on May 2, 2005, at the Boston Athenaeum, when Termeer, along with two biotech colleagues, Patrick J. Sullivan, and Michael Astrue, discussed recommendations to Massachusetts policymakers and legislators on how best to grow the innovative life sciences industry cluster.

The message coming out of that meeting was: “Invest in the creation of a collaborative culture of predictability and persistence.”

That event – and the advice that Termeer and his colleagues offered – helped to change the trajectory of the life sciences industry cluster in Massachusetts. It led directly to the creation of the $1 billion Massachusetts Life Sciences Initiative. It also led indirectly to the creation of an academic research consortium in Massachusetts and the launch of Mass Challenge.

It is a story that could have great resonance for Rhode Island, which now finds itself at a similar crossroads in how to develop and nurture its life sciences industry sector.

Setting the stage

The conversation in 2005 took place in what today seems like a distant memory of a place that existed long ago and far away in a distant galaxy: the life sciences industry, while prospering in Massachusetts, was rife with dissonance, with many competing voices.

A previous attempt to align and find common ground within the industry sector, at a 2003 Life Sciences summit, led by Michael Porter, director of the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness at Harvard, and Lawrence Summers, then Harvard University president, had fallen apart into bickering over turf between competitive companies and universities.

The Life Sciences industry cluster was, in today’s parlance, in the midst of a growth spurt, but it was locked in a global competition with other technology states – including North Carolina, California and New York – as well as with other countries for talent, venture capital and government incentives.

Mitt Romney was then the Governor of the Commonwealth, and he and his advisors were beginning to contemplate the possibility of a run for the Presidency in 2008. [Indeed, Romney’s team actively explored the idea of hosting a conference in 2005 with author Thomas Friedman as the keynote speaker as a way to jumpstart Romney’s economic profile.]

In 2005, the life sciences industry cluster itself was a complex array of public and private sector entities employing more than 600,000 Massachusetts residents, contributing some $26 billion to the Commonwealth’s economy, according the Mass. Index of the Innovation Economy.

The initial policy recommendations discussed at the May 2 event addressed four strategic areas: job retention and creation; R&D, technology transfer and commercialization, workforce development; and life sciences industry cluster development. A fifth area, state regulatory support for small to mid-sized companies, was added following the discussion.

Those policy recommendations were forwarded to the Mass. Legislature’s Joint Committee on Economic Development and Emerging Technologies, serving as the foundation of legislative policy discussions. [Would that the R.I. General Assembly create such as joint committee.]

With the election of Gov. Deval Patrick in 2006, the recommendations, particularly around the life sciences industry cluster, became an economic development priority.

Here’s what Termeer had to say at that pivotal 2005 gathering.

Toward a culture of cooperation

Termeer spoke at length about the future of the biotech industry. He predicted that the industry would change, responding to the creation and delivery of specific medicines that worked with greater predictability, much different than what he described as the current trial-and-error methodology.

The future biotech industry, Termeer predicted, will feature “smaller facilities, be more labor intensive, and require more intimate connections” in the translational effort to bring new efforts to the marketplace.

Further, Termeer counseled that instead of thinking about the immediacy of “next year,” Massachusetts needed to think in terms of “ a 10- to 20- to 30-year framework” for investment.

Termeer also cautioned against investing everything in specific technologies, such as stem cell research. Rather, he urged policymakers to foster “a culture of cooperation” between business, academia and government.

The consensus of the meeting was that the state needed to focus on a multi-year effort, not a one-shot event, demonstrating a persistence and a predictability in its policy efforts.”

The technology exponential

Four years later, on June 10, 2009, at a gathering at Microsoft Research and Development Center in Cambridge, Mass., a consortium of academic research centers, private firms and the state of Massachusetts convened an all-day conference, “A Framework for Collaboration in the Region’s Information Technology Sector.”

It was, in many ways, a direct outgrowth of the policy discussion held in May of 2005, at which Termeer talked about creating a culture of collaboration. At this gathering, the focus was on collaboration in IT, computing, robotics and academic research.

It was at this event that Gov. Deval Patrick officially launched the MassChallenge venture funds competition, which was described as “an initiative to improve the environment for entrepreneurship and business formation in the Commonwealth.”

Greg Bialecki, then Secretary of the Mass. Executive Office of Housing and Economic Development, described his vision of the collaboration at the June 10 event: “To create and sustain what is widely recognized as the most effective collaboration of industry, academia, and government in support of technology and innovation in the world.”

The next day, on June 11, Patrick was joined by then MIT President Susan Hockfield, then University of Massachusetts President Jack M. Wilson and then Boston University President Robert Brown, to sign a memo on intent to create a high-performance, green computing center in Holyoke, Mass.

Rodney Brooks, the co-founder of iRobot and the former director of the MIT Computer Science and Artificial Laboratory, gave the keynote address at the June 10 event.

In his talk, Brooks invoked the legacy of an article published in 1965 by Gordon Moore, the founder of Intel, in which Moore predicted how integrated electronics was going to change the world.

“[Moore] predicted that we are going to get home computers – remember, he said this in 1965, when computers costs millions of dollars and filled many room. He said we are going to get automatic controls for automobiles. He also said that we are going to get personal, portable, communications equipment. Cell phones.”

Technology exponentials, Brooks continued, “beget social exponentials,” predicting that changing age demographics in the U.S. and Japan meant that tasks being done by workers aged between 20 and 65 was going to diminish, resulting in productivity needing to be increased through IT and robotics.

Lessons for Rhode Island

There are stirrings within the economic development sector on how best to exploit the potential of the emerging biotech industry cluster in Rhode Island. A version of MassChallenge is coming to Rhode Island. There are innovation vouchers for research. There are new investments in translational research. There is a collaborative framework around neuroscience research. MedMates is attempting to organize a life sciences industry cluster. There is a new research hub at URI with a partnership between MindImmune and the university.

Companies such as EpiVax and IlluminOss continue to grow, showing enormous potential to bring their products to the marketplace based on great science and talent.

So, what will it take to create and sustain a collaborative culture focused predictability and persistence in Rhode Island?

What’s missing, in large part, is the kind of forum where there is an inclusive conversation around policy with legislators, corporations, academic researchers and talent, which does not yet exist in Rhode Island. A key feature of such a forum is the need for government to listen, and not to control the conversation, talking at folks.

In addition, to paraphrase the lyrics from the musical, “South Pacific,” there is a need to focus not on what we have, but rather, what ain’t we got.

• There is no comprehensive annual index of the innovation economy for Rhode Island; we are still measuring economic benchmarks by outdated metrics.

• There is no ongoing legislative commission or joint committee to provide members of the R.I. General Assembly with a way to educate themselves around policy discussions and investments in the emerging innovation economy.

• There is no adequate flow of resources, money and entrepreneurial talent to support companies beyond the startup stage in Rhode Island. Promising entrepreneurs, even former winners at MassChallenge and at the Rhode Island Business Competition, have been forced to walk away from their entrepreneurial dreams.

• There is too much emphasis on short-term job creation, instead of long-term sector growth. The process of innovation is long-term, often with any numbers of failures before success, yet much of the current investment model in the innovation economy in Rhode Island has been framed by a jobs equation within the framework of winning the next election.

• There is a disconnect between investments in products to serve the health care delivery system and Big Pharma and efforts to decrease the social, economic, environmental, and health disparities. Beyond workforce development and enticing companies to relocate in Rhode Island through tax incentives, there is a need to focus on health equity, not just profits as part of a wealth extraction system.