All the news that gets ignored

Six accountable entities were certified last week by EOHHS as the alleged backbone of the Reinvention of Medicaid, but the calculation appears to be more about sharing the wealth than shared savings

Perhaps that is a message to be taken to heart by the state officials pushing ahead with accountable entities: where are the patients’ voices to be found in this social engineering effort around the flow of Medicaid money?

PART ONE

PROVIDENCE – On Wednesday, May 2, with no fanfare and no formal media advisory, the R.I. Executive Office of Health and Human Services announced in an email to ConvergenceRI that six health care providers had received notification that they had been conditionally certified as “accountable entities.”

[Enshrined in law as part of the Reinventing Medicaid Act of 2015, the goal set for the state was to have 50 percent of all Medicaid payments made through alternative payment models such as accountable entities by 2018, and to have 25 percent of all Medicaid members enrolled in an accountable, integrated provider network by 2018.]

The accountable entity initiative had been envisioned as the backbone of Rhode Island’s Medicaid reinvention effort. But, after the dust cleared following a two-year pilot, the major result appears to be more about sharing the wealth than achieving shared savings, according to a number of sources.

Two hospital systems [Care New England’s Integra and Prospect Medical, the for-profit owner of CharterCare] and a large physician group practice [Coastal Medical Group] have gained access to the stream of managed Medicaid money, in addition to community health centers.

Further, the concept of a proposed accountable entity focused on long-term care services, targeting skilled nursing facilities, appears to have been abandoned as being unworkable, according to four sources.

Ironically, one of the stated goals of accountable entities under the Reinvention of Medicaid initiative was to shift Medicaid expenditures from what was termed “high-cost institutional settings” – skilled nursing facilities – to community settings as appropriate.

As the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services described long-term care service benefits, “Millions of Americans, including children, adults, and seniors, need long-term care services because of disabling conditions and chronic illnesses. Medicaid is the primary payer across the nation for long-term care services.”

[The proposed cuts in state funding to protect services and rights for adults with developmental disabilities is an entirely different can of worms, potentially jeopardizing the 2014 federal consent decree. as documented by the reporting of Gina Macris in Developmental Disability News. See link below to Macris’ latest reporting.]

Not having a certified accountable entity or even a pilot dedicated to long-term care services means that burden may fall upon the remaining six certified accountable entities, which one source called a dishonest, bait-and-switch approach.

When asked for a response about the apparent snafu, Ashley O’Shea, spokeswoman for R.I. EOHHS, told ConvergenceRI: “We’re continuing to explore ways to transform how we deliver and finance long-term support services in Rhode Island. And, we will keep you closely posted as this work continues.”

Chassis for the future?

At a meeting of the State Innovation Model steering committee on March 8, Patrick Tigue, the director of the R.I. Medicaid office, called accountable entities “our chassis for the future” and the state’s “most significant reform effort,” according to minutes from the meeting.

As Tigue explained it, the development of accountable entities is being financed through the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services through what is known as the Health System Transformation Project. It enables Rhode Island to draw down Medicaid funds that are tied to reforming the service delivery system, referring to a source of federal funds that has the acronym of CNOMs, or costs not otherwise matchable, to be spent on transforming Medicaid systems in Rhode Island.

Rhode Island received roughly $100 million in such funding to support investments in accountable entities, which was announced at a Nov. 28, 2016, State House news conference. [See links below to ConvergenceRI stories, “A peek behind the curtain at reinventing Medicaid 2.0,” and "How do you become an ACO: That is the question."]

The goals of the accountable entity program, articulated in Tigue’s presentation to the SIM steering committee, were as follows:

• Substantially transition away from fee-for-service models [of reimbursement].

• Define Medicaid-wide population targets [consistent with SIM], and link any incentive payments to performance.

• Deliver coordinated, accountable care for all, with targeted support for high-need/high-cost populations.

• Shift Medicaid expenditures from high-cost institutional settings to community settings as appropriate.

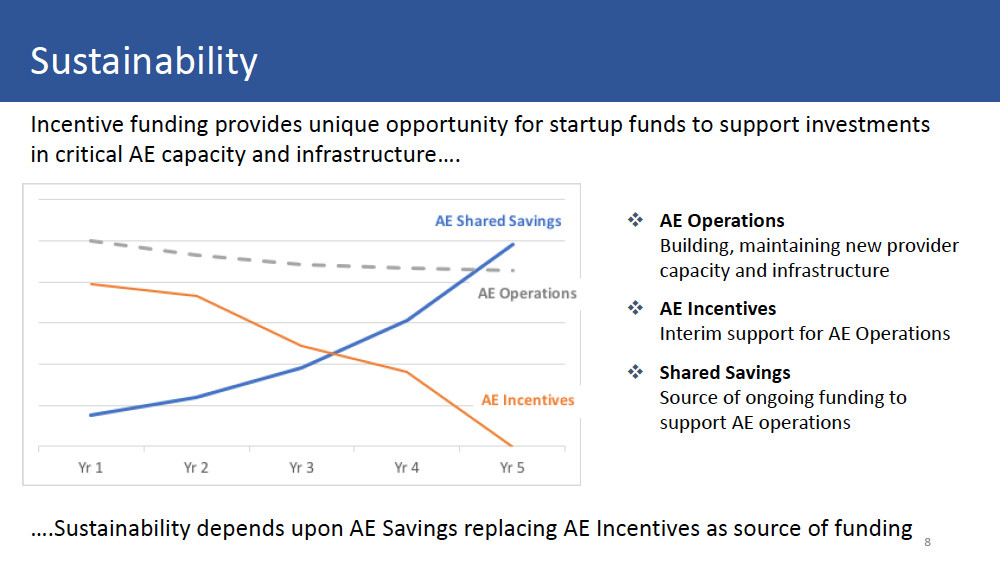

As part of the presentation, Tigue presented an optimistic view of the projected results of the accountable entity program, what people in the start-up entrepreneurial world often refer to as a “hockey stick” projection of success, where shared savings increased in direct proportion to interim incentives for accountable entities diminish. [See illustration above.]

Tigue’s optimistic view, however, was not shared by those on the ground who were tasked with managing the delivery of care for Medicaid patients.

As one community health center practitioner told ConvergenceRI, describing the process of how the state was implementing accountable entities, “It is not just a clusterf***, it gives clusterf*** a bad name.”

The basic facts

Since late 2015, many of the same providers in the accountable entity playing field had been participating in a pilot program.

The newly certified six accountable entities include: two hospital systems, one large physicians group, two community health centers, and an amalgamation of six other community health centers operating as one entity.

They are: Blackstone Valley Community Health Care; Providence Community Health Centers; Community Health Center ACO, an alliance of six of Thundermist, East Bay CCAP, TriCounty, WellOne and Wood River community health centers; Care New England’s Integra, Coastal Medical Group; and Prospect Medical [the owner of CharterCare].

A brief primer on health care policy

To better understand the efforts to reinvent Medicaid and the forces behind it, and with it, the drive to create accountable entities, it requires taking a step back and view the broader health care landscape.

• In our current health care delivery system, more than 60 percent of the health care spend in the U.S. is driven by federal health insurance reimbursements through Medicare and Medicaid. None of that money goes to Medicaid or Medicare members per se; it goes to hospitals, providers, insurers and pharmacies for services allegedly provided to patients. The discrepancies about what gets charged for an emergency room visit or an urgent care visit best exemplifies the disparities – and the lack of transparency – in medical costs.

The perverse corollary is that in Rhode Island, the health industry sector is an economic engine generating one-sixth of the state’s economic product, where hospitals are the leading private employer, where future job growth is tied to expansion of the nursing needs generated by the health industry sector, and where the academic medical research enterprise has emerged as the jewel in the crown of the state’s future innovation economy.

At the same time, expansion of integrated primary care, particularly for underserved populations, has been found to lower costs and boost wellness and prevention, particularly for women and children, through the existing network of community health centers and the development of patient-centered medical home practices.

• The urgency to transform and reinvent Medicaid in Rhode Island is driven by two converging forces: efforts to reduce spending under the state budget, under the guise of rooting out waste, fraud and abuse; and the need to find a scapegoat for ever-increasing medical costs – when in doubt, blame the poor as somehow being undeserving.

The basic political question is this: is having a large number of residents on Medicaid a sign of economic weakness, rather than an indication of economic strength?

Is there anyone who will argue publicly against investing in access to preventive health care for young mothers and newborns as the best prescription for future healthy lives, improving educational achievement and economic attainment opportunities? Good question.

Still, there is also no denying the fact that the state Medicaid budget in Rhode Island keeps growing – directly linked to ever-increasing medical costs and rising Medicaid enrollments. The major driver of this cost escalation are the demographics of skilled nursing care: as the state’s aging population gets older, and as chronic diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, diabetes and heart disease, flower and peak, it often requires 24/7 care in a skilled nursing facility. Medicaid becomes the last resort after a person’s other financial resources have been exhausted.

[There is a booming legal business for wealthier residents to hide their assets so they can qualify for Medicaid and pass their largesse onto their family, putting the burden on the state to pay for their care.]

The botched rollout of the $492 million Unified Health Infrastructure Project, or UHIP, which the state keeps trying to re-brand as RI Bridges, which resulted in massive, continuing delays in the state certifying Medicaid eligibility for clients, has severely damaged state’s long-term care infrastructure. In addition, the Deloitte-built software system has created glitches in determing who is eligible and who is no longer eligible for state-sponsored benefits.

See Jane running, chasing Spot

It is important to remember that members enrolled in Medicaid do not see any of the cash themselves.

Money from the Medicaid money tree flows first to state Medicaid offices, which administer the programs in partnership with the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, with the feds and the state roughlly shring the costs in a 50/50 ration.

Then the money flows to medical providers, but it must first pass through the middle men and women, through what are known as Medicaid managed care organizations, or MCOs, health insurance companies, which take the next cut.

In Rhode Island, there were two such MCOs, Neighborhood Health Plan of Rhode Island, and UnitedHealthcare of New England. Neighborhood had about two-thirds of the market, and United one-third of the market. As part of the Reinvention of Medicaid, a third MCO was added to the market, Tufts Health Plan. [Tufts, however, does not have enough “customers” to participate in an accountable entity program.]

The money chase works like this: the state Medicaid office sets the capitation rate [the rate per Medicaid member per month for the cost of care] and pays this to the MCOs. This is intended to cover all medical costs for the patients assigned to the MCO or to the MCO that the patient chooses during initial sign up with Rite Care or during any open enrollment periods thereafter.

The brass ring to grab onto for an accountable entity is to manage the total costs of patients attributed to them in such a way that the total cost is below the capitation rate that the MCO received from the state.

This is done, as one community health care practitioner described it, "by keeping people healthy, by keeping them out of the hospital, and by providing more accessible hours so patients stay away from the emergency room."

However, the pool for shared savings under the accountable entity initiative is not based upon saving money relative to the state capitation rate received by the health plan.

Rather, the pool is based on how much lower per member per month costs achieved one year are compared to the previous year.

Translated, the lower cost providers are competing against themselves; it is very hard to move the needle from total cost of care, say, $2.10 to $2 per member per month. Instead, those higher cost providers that can show the most improvement in year to year comparisons, say from $20 per member per month to $10 per member per month, stand to reap the most shared savings.

The upshot is this: Are the state and the Medicaid MCOs attempting to balance their budgets and rebuild their balance sheets on the backs of the performers who are generating the real costs savings?

And, will those "shared savings" disappear when the money from CMS as part of the Health System Transformation Project ends in four-five years?

The question is: Should shared savings under the Medicaid accountable entity initiative in Rhode Island reward the providers with the lowest total cost of care, or the providers with the greatest improvement in a year to year comparison? Stay tuned.