Making it happen in Rhode Island

A full-day session, convened by the Rhode Island Foundation, turned the Convention Center into a big classroom, with the goal of achieving consensus about how best to build a world-class public education enterprise in the state

PROVIDENCE – With just 18 shopping days before Christmas, on Saturday, Dec.7, the Rhode Island Convention Center was transformed into a huge classroom exercise, call it a one-day university, corporate style, to attempt to fashion a consensus response to a draft strategy for a 10-year plan for the future of public education in Rhode Island for pre-K through 12th grade.

Some 400 invited participants – including parents, teachers, students, principals, superintendents, legislative policy directors, nonprofit CEOs, former hospital CEOs, community agency directors, education advocates, child health advocates, principals, superintendents and a few members of the news media, were tasked with identifying what was missing from the draft strategies that had been developed by a working group of stakeholders, known as the Long-Term Education Planning Committee, convened by the Rhode Island Foundation, in partnership with the R.I. Department of Education.

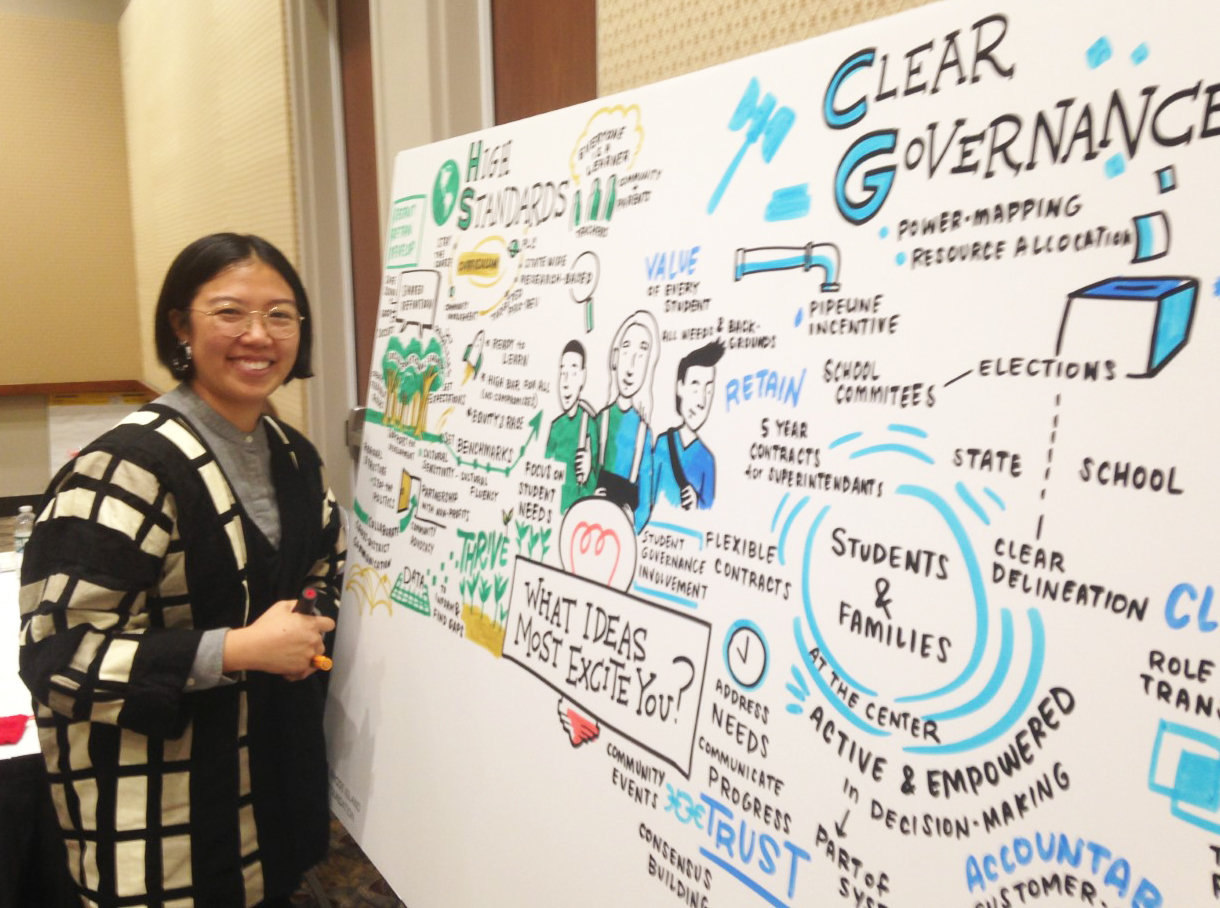

In a series of facilitated breakout sessions, with roughly 40-50 people designated to a room, participants discussed strategies around four articulated goals – investment priorities, high standards, educator support and clear governance, in facilitated conversations. The contents of each conversation from the different tables was reported back to the group, and then captured and translated into pictographic charts. [See second image above.]

The day was laden with heavy-handed messaging: big letters spelling out the word, PROMISE, in all caps, dominated the stage. It served as a backdrop for professional “selfies” to be taken, including with the R.I. Commission of Education Angélica Infante-Green. [See first image above.]

A three-fold glossy brochure featured a cover invocation of the vision: “Rhode Island’s world-class public education system prepares all students to succeed in life and contribute productively to the community.” The back cover preached: “Chart a Course, Stay the Course,” as the way to create Rhode Island’s path to a world-class public education system.

Indeed, consulting firms such as McKinsey & Company or Deloitte could not have designed a better engagement strategy.

Locking arms together

The tone was set in introductory remarks by Neil Steinberg, president and CEO of the Rhode Island Foundation, who declared that the secret sauce in Massachusetts’ success in achieving better education outcomes was: “Staying the course for 25 years.”

Commissioner Infante-Green, in her introductory remarks, echoed the need for everyone to be on the same page, saying that Rhode Islanders needed “to lock arms together” and move forward, or risk being left behind. “I promise I will always put kids first,” she said. “We are going to be number-one in the nation.”

In the morning breakout session

The table that ConvergenceRI sat down at had a high number of principals, many seemed to know each other. Birds of a feather flock together.

The first task was to review the strategies listed under “High Standards” and “Clear Governance” and identify anything that might be missing. The second task was to identify the best tactics on how to make it happen.

For the record, the draft strategies for “High Standards” were:

• Implement standards-aligned curriculum and instruction statewide that is both grade-level appropriate and culturally responsive

• Sustain a rigorous, statewide assessment system.

• Establish expectations for positive school culture, safe school environments, and meaningful parent and caregiver engagement – at the state and local level.

• Provide students with opportunities for internships and work experience, through robust college and career pathways.

• Establish statewide standards for multilingual education.

Not surprisingly, the participants at the table poked some big holes in the draft strategies, identifying the need to have a researched-based curriculum, instead of texts that had Common Core Approved stamped on them. Further, the participants lamented the silo-ed approach between schools, with an inability to share experiences about what worked and what didn’t in the classroom, across districts. And, the inability to share resources.

In addition, the participants questioned the purpose and value of an assessment system in which teachers were not allowed to be flexible in their roles, depending on what the students’ needs were. Other participants questioned what happened with the adoption of the RICAS, which employed a 13-year-old system, without updating it.

Others wanted a clearer definition of what equity meant around cultural competency. Another problem identified was the different expectations of teachers, who had grown comfortable with roles. There was no ability to support such teachers and provide them with an opportunity to retool their skills.

One principal talked about her son, now a freshman in college, who found himself unprepared for the digital format of his learning platform at the university level.

Under “Clear Governance,” the draft strategies were:

• Engage communities, including parents, caregivers and students, to be part of the decision-making process.

• Commit to school-based management. Provide district and state support for policy, professional development, and technical assistance.

• Align responsibility and authority at each level of governance.

• Review outcomes and accountability, including rebuilding statutes and regulations where necessary.

Once again, the participants at the table proceeded to poke some big holes in the proposed strategies. As much as the comments were captured by note takers and translated into a pictographic, there was worry voiced about whether the comments would become homogenized in the final analysis.

One problem identified was the fact that those in charge of administering school policies, such as school boards, often lacked professional expertise to evaluate the success of teaching programs. They were bankers or lawyers, but were unfamiliar with education standards.

In addition, because students learn at different rates of speed, the participants were wary of governance standards that created standards for success, without being able to identify what a student can do, rather than what a student cannot do.

There did not seem to be any language around process or around social and emotional learning, or clear definitions around “responsibilities.”

Finally, the draft strategies failed to address the “adaptive” component of learning and education.

Lunch discussions

Not everyone attending the event bought into the process or messaging, which became clear from a number of conversations at lunch. Members of the group, Providence Promise, lamented what they saw as the lack of outreach into the community to enable more people to participate in the day’s deliberations, which they saw as top-heavy with administrators.

Another participant cited the need for a more student-centered approach, one in which students had an authentic voice in decision making. The participant feared that “the baton was being passed to another administrator” who was not going to be able to fix everything.

Second verse, same as the first

The afternoon session proceeded much like the morning session, with a facilitated conversation talking about the draft strategies for investment priorities and educator support.

Everyone then reconvened to hear a panel featuring Gov. Gina Raimondo, R.I. Senate President Dominick Ruggerio, state Rep. Joseph McNamara, chair of the House Committee on Health, Education and Welfare, and Commissioner Infante-Green, to give their public response to a brief overview of the day’s findings, with the Rhode Island Foundation’s Neil Steinberg serving as moderator.

All heaped praise on the work done by Steinberg as a leader in convening working groups on education and on health.

Gov. Raimondo said that she was all in on efforts to develop a world-class public education enterprise, promising to make it a cornerstone of her second term. “It is time to lean in,” she said, arguing that it was important not to sacrifice the good in pursuit of the excellent.

Ruggerio talked about the need to attract and retain teachers, saying that Providence currently needs about 90 teachers. He also emphasized that everyone has to be rowing in the same direction, to be reading from the same sheet of music.

Infante-Green spoke in what seemed to ConvergenceRI to be a snarky tone of voice, saying that she was surprised that so many Rhode Islanders had turned out for a full day of classroom work and not gone shopping at the mall. “If we get caught in adult politics,” she warned, “we will lose,” saying she was not going to be dissuaded by criticism of her management style. “I don’t need luck; I need partners.”

What was not discussed

One topic not on the agenda was the current lawsuit being brought in U.S. Federal District Court in Rhode Island to establish a constitutional right for students to receive a civics education.

As Chanda Womack, who describes herself as a optimist, feminist, reader, observer, learner and educator, tweeted during the event: “Dearest @RIFoundation, your vision cannot be achieved without an adequate civics education. Charting a meaningful course requires systems/institutional change. This requires you, largest foundation in RI to support Cook v. Raimondo.”

At the all-day session, ConvergenceRI caught up with Jennifer Wood, the executive director of the Rhode Island Center for Justice, the nonprofit that is bringing the suit, which had a hearing argued before Judge Smith two days before the Saturday gathering.

ConvergenceRI: So what did Judge Smith say?

WOOD: Judge Smith, right out of the blocks, really wanted to interrogate the question, of what kinds of actions can the state take in education policy that would be sufficient to trigger a Constitutional protection.

He took the approach, if we assume for the moment that the U.S. Supreme Court has left this door open to answer that question, he then wanted to know from the state, “How much is enough? What if we were to cancel math? Does that have a Constitutional dimension?”

And, I think the state’s attorneys tried to say [Anthony Cottone on behalf of the Education Commissioner] that they believed that the state and the local districts could make any decisions they want about education. But Judge Smith pushed the issue to say, “What about if the state decided to just shut down public education and provide no public education to young people in the state? Would that have a Constitutional dimension?”

And, Mr. Cottone, on behalf of the Commissioner, to his credit, said: “I think we couldn’t do that. I think that has a Constitutional dimension.”

So, for us, now we’re talking about how much education is enough to meet that Constitutional dimension?

ConvergenceRI: Is that similar to the question once posed by George Bernard Shaw about haggling over price?

WOOD: I have been using that analogy, sir. Basically, you’ve agreed to the principle; now we’re just bickering about the amount.

I was extremely thrilled on behalf of Rhode Island’s students and frankly, the nation’s students, that there may be some acknowledgement that there is fundamentally, U.S. Constitutional protection.

Now, we would need to interrogate, through the usual process of the courts, how much education is enough, and is guaranteed to young people to protect their right to exercise their Constitutional rights like free speech, voting, participation in democracy.

ConvergenceRI: Does the current impeachment hearings now underway lend itself to something that is left out of civics education?

WOOD: Judge Smith noted, in the questioning of the attorneys on Thursday morning, that the New York Times had published a recent finding from the international comparison of student capabilities that only 13 percent of U.S. students can distinguish between fact and opinion presented in written form.

And he expressed alarm, which I would think we would all share, that how could we possibly ask people to make judgments as voters, and ask elected officials to make judgments on questions like impeachment, if 87 percent of the populace cannot distinguish between fact and opinion.

ConvergenceRI: Where does the case go from here?

WOOD: Judge Smith took all of the arguments under advisement and we expect that he will issue a written decision on the state’s motion to dismiss sometime in the coming months.

At this stage in the litigation, if Judge Smith denies the state’s motion to dismiss, then we will go forward through the fact-finding process, referred to in the law as discovery. And move forward to a trial here in Rhode Island about what quantum of education are students entitled to under the U.S. Constitution.

Talk about a courtroom drama playing out in Rhode Island that would change the proposed educational strategies around curriculum moving forward.