Mining the golden ore of clinical data

New statewide clinical dataset on obesity in Rhode Island’s children and teens reveals the largesse of the problem

In January of 1977, I covered the inauguration of President Jimmy Carter, where Aretha Franklin also sang, which I was privileged to hear in person. In my reporting on the inauguration, I called the story: “I heard America singing,” invoking a line from poet Walt Whitman, in a kind of hopeful prayer.

As Rhode Island attempts to grapple with the cultural divide around health disparities related to obesity, there is an opportunity for the dignity and respect that Aretha Franklin embodied in her music to build a culture of health, not one of hatred and fear.

PROVIDENCE – One of the more fascinating data projects conducted by the State Innovation Model has been an attempt to cull all the existing databases concerning obesity in Rhode Island for children and teens by seeking to track data for BMI, or body mass index, broken down by age, sex, race, ethnicity, and town.

BMI is not only an indicator for obesity but also considered a precursor for the development of Type II diabetes, a chronic disease that is one of the scourges of our culture, devouring more and more of our health care dollars each year, with the insatiable appetite of a very hungry parasite.

Such data could have a profound application in population health management, according to numerous public health professionals, depending upon how it is used.

The preliminary results of the effort, known as the “Clinical Child BMI Data Work Group Project,” were presented at the most recent SIM Steering Committee meeting on Aug. 9.

[Consider this story to be breaking news: there have been no news releases, policy briefs or even “public” sharing of the presentation and its findings yet; it has not even yet been published as part of the official minutes from the meeting.]

Newsworthy

The preliminary findings were extremely newsworthy; they revealed that obesity among Rhode Island children and teens is a fundamental health disparity tied to race and ethnicity:

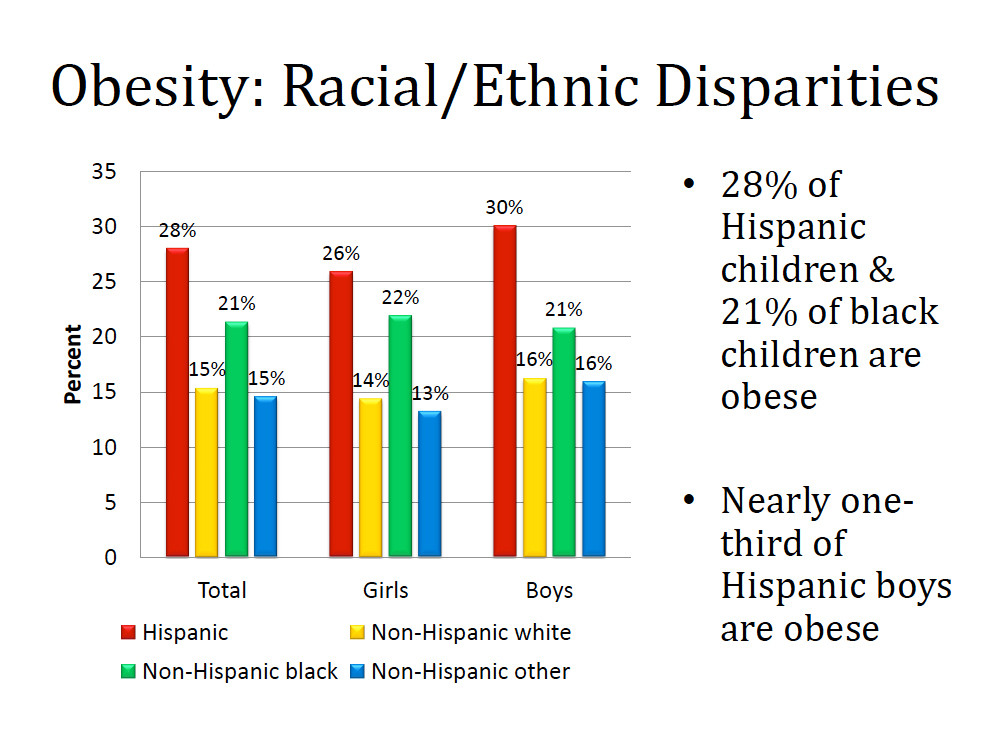

• 28 percent of Hispanic children and 21 percent of black children in Rhode Island were found to be obese, compared to 15 percent of white children.

• Nearly one-third of Hispanic boys and more than one-quarter of Hispanic girls were found to be obese.

Further, the obesity numbers using BMI metrics were then correlated according to Rhode Island cities and town, showing the prevalence throughout the state. Looking into the mirror, the scorecard did not reflect an image of health:

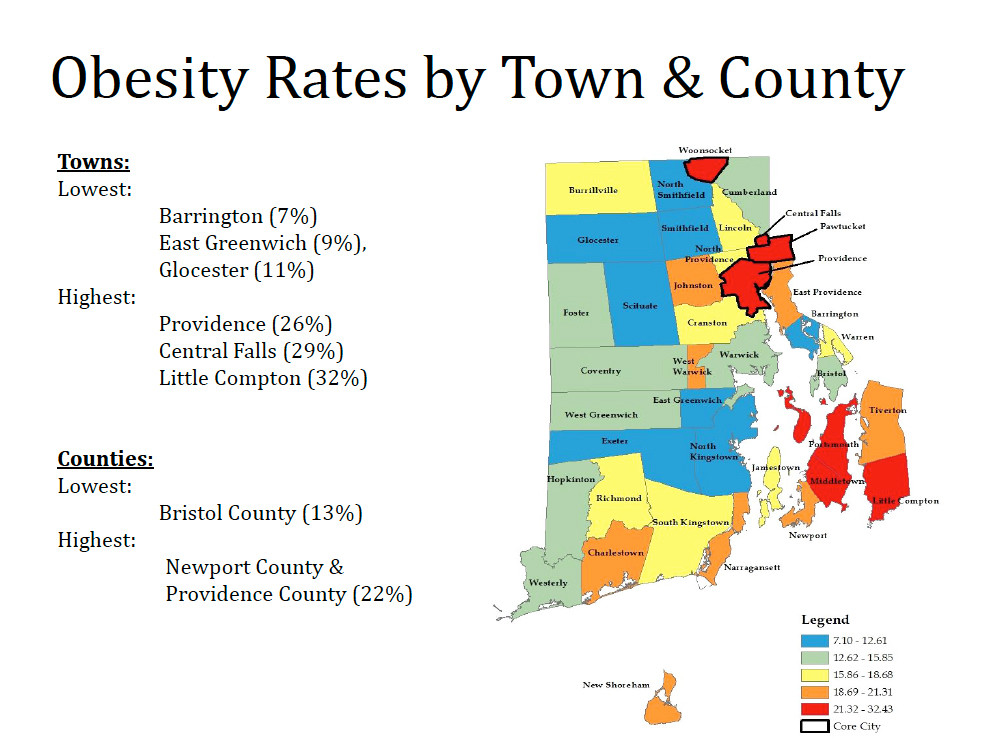

• The highest rates [21 to 32 percent] of obesity for children and teens in Rhode Island were found in Woonsocket, Central Falls, Pawtucket, Providence, Portsmouth, Middletown and Little Compton.

• The next highest rates [18 to 21 percent] of obesity in children and teens were found in East Providence, Newport, Narragansett, Johnston, Charlestown, Tiverton, West Warwick and Block Island.

• The third highest rates [15 to 18 percent] of obesity in children and teens were found in Cranston, Lincoln, South Kingstown, Richmond, Warren and Burrillville.

Translated, more than half of the communities in Rhode Island had rates of obesity based upon BMI metrics for children and teens between the ages of 2 and 18 greater than 15 percent.

• The lowest rates [7 to 12 percent] of obesity in children and teens were found in Barrington, East Greenwich, North Kingstown, Exeter, Scituate, Glocester, North Smithfield and Smithfield.

The data mapping of obesity in children and teens by BMI data in Rhode Island seemed to confirm what many public health researchers have found previously: poverty and wealth appear to be contributing factors, particularly for those living in food deserts and in fast-food swamps, without easy access to fresh fruits and vegetables.

Story within the story

With all the noise about the promise of how leveraging health IT will rescue the U.S. from the deluge of ever-escalating medical costs [such as the new enterprise by Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway and Goldman Sachs], there was a distinct story within the story, call it a wheel within in a wheel, about the work of the “Clinical Child BMI Data Work Group Project,” with great relevance and import to such efforts: how existing data is shared – or not shared – in regard to managing population health.

The challenge for the Clinical Child BMI Data Work Group was to attempt to capture all the data available about BMI metrics for children and teens in Rhode Island that had not yet shared or integrated into one database.

As Devan Quinn from Rhode Island KIDS COUNT, a member of the working group, explained it: the project was “a proof-of-concept effort to determine if it was possible to collect a representative sample of statewide clinical BMI data for children ages 2-17.”

Although there is an ongoing national epidemic of childhood obesity, Quinn told ConvergenceRI, “There were no clinical sources of BMI data on a state level [in Rhode Island] that could be broken down by age, sex, race, ethnicity, and town.”

In addition to Quinn, the working group included an impressive roster: Dr. Michelle Rogers and Dr. Patrick Vivier from the Hassenfeld Child Health Innovation Institute; Carolyn Belisle from Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Rhode Island; Ellen Amore from the Center for Health Data and Analysis at the R.I. Department of Health; Jim Beasley, formerly of Rhode Island KIDS COUNT; Libby Bunzli from the R.I. Office of the Health Insurance Commissioner; and Melissa Lauer from the R.I. Executive Office of Health and Human Services.

Each of the current existing public databases on BMI metrics for children and teens in Rhode Island presented a small, incomplete picture:

• The base data file from KIDSNET, the state’s database, contained information for 248,001 children and teens who were older than 2 years but younger than 18, as of Dec. 31, 2016. But KIDSNET contained BMI data for only 4,636 children and teens, a scant 1.9 percent of the total population, culled mostly from WIC [Women, Infants and Children food and nutrition services] data inputs.

• Similarly, CurrentCare, the state’s vaunted health information exchange, had BMI data for only 7,446 children and teens, some 3 percent of the total population.

The health insurers – including Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Rhode Island, Neighborhood Health Plan of Rhode Island, and UnitedHealthcare – had collected much more data about BMI metrics for children and teens in Rhode Island, but the data had been mostly kept to themselves and not shared with government health agencies or with competing plans.

The Clinical Child BMI Data Work Group sought access to that data, in a de-identified fashion, from Medicaid managed care organization data. The work group provided to the insurance plans the ID number of members with no BMI data in KIDSNET and CurrentCare.

The insurance plans responded by sharing a more complete BMI dataset, with any related BMI codes added [ICD 9, ICD 10, or HCPCS], which showed actual height and weight and BMI. All such data files were de-identified and analyzed for “representative-ness” of the state.

Even with the health insurers’ participation, there remained a significant gap on BMI data, according to the presentation. About 51 percent, or 126,407 out of 248,001 Rhode Island’s children and teens as of Dec. 31, 2016, were not part of a managed care organization file containing BMI data or had no BMI data as part of their KIDSNET or CurrentCare files.

As Quinn explained it to ConvergenceRI, despite the gap, the work group had been able to collect a statistically significant sample: “In this collection process, 18 percent of returned files, amounting to [more than] 44,000 de-identified records, had BMI-related data.”

The work group then evaluated the data and found it to be a representative sample, Quinn continued, reflecting the age, race, ethnicity and town distributions of the overall child population of the state.

“This proves that the proof-of-concept worked; we were in fact able to collect clinical BMI data at a state level, and it was a representative sample of the state,” he said.

The statewide clinical BMI data sample provided strong statistical evidence, broken down by age group, of the epidemic of obesity in Rhode Island for children and teens:

• Overall, for ages 2 through 17, 20 percent of children and teens in Rhode Island were obese and 15 percent were overweight.

• The highest percentages were for children and teens ages 10-14 in Rhode Island, with 23 percent obese and 17 percent overweight.

Next steps

Quinn said that it will take some time to further analyze the data, and that Rhode Island KIDS COUNT planned to publish findings from this project in an upcoming policy brief.

Lynn Blanchette, Ph.D., RN, Associate Dean and Assistant Professor at Rhode Island College School of Nursing, and a frequent observer at the SIM Steering Committee meetings, called the project “an interesting case study about data sharing, federal and state regulation and lack of understanding about population health,” adding that she thought Amore and the working group team deserved big recognition for their work.

Further, Blanchette said: “I think the work they did really demonstrated all the places where groups hold data, [but] don’t understand the role of population health/public health data for program planning.”

Dr. Peter Simon, an Associate Professor of the Practice of Epidemiology at the School of Public Health at Brown University, lauded the work group’s efforts, saying: “See what can be done when people collaborate.”

Simon provided some further context: The work group “followed the same protocol we [at the R.I. Department of Health] developed many years ago to get lead screening rates for each MCO [managed care organization] so [that they could] qualify for incentives in contracts with Medicaid.”

Simon concluded: “These folks could have done this years ago if they had been incentivized to do it.”

Food for thought

A recent series of qualitative focus groups in a Midwestern, Hispanic/Latino community, the results of which were published in a recent issue of Health Promotion Practice by the Society of Public Health Education, provided some insights of how Rhode Island could respond to the preliminary findings of the “Clinical Child BMI Data Work Group Project,” particularly as it related to the findings that a large percentage of Hispanic children and teens were overweight and obese.

The write-up of the study began: “One of the largest, increasingly diverse, and fastest growing populations in the United States is the Hispanic/Latino population; thus, developing community-based health initiatives that meet this community’s needs is imperative because of the unequal burden of disease they experience.”

Existing research demonstrated, the study continued: “Hispanics/Latinos are more likely to experience negative health outcomes, chronic disease, obesity, reduced physical activity, and under-consumption of recommended produce servings. While public health campaigns attempt to alter long-term health behavior and decision making among Latinos, current research indicates “one size fits all” public health campaigns are not successful because they are not inclusive of diverse, lived experiences.”

The study concluded: “Developing essential public health programs to increase healthy food and physical activity opportunities and the selection of healthy habits in the Hispanic/Latino population requires understanding their local environment is multidimensional. As community members exist in a culture with a built environment that has an abundance of foods that are fast, easy, and have low-nutritional value, and they have a limited number of socioeconomic resources and social supports in the local environment.”

Further: “Our study demonstrates the need to develop programs that account for these environmental challenges faced by individuals, families, and local communities when they are choosing healthy lifestyle choices. Interventions focused on improving healthy food consumption and healthy choices that are aware of these challenges can adapt accordingly to become more culturally sensitive and appropriate, potentially increasing food equity and decreasing health disparities in the Hispanic–Latino population.”

Finally: “Other important issues that need to be addressed in future research are asking questions that explore in more depth socio-cultural norms, the assimilation process, differences in male health perception [as our study is predominantly female], decision making, as well as perceptions of cultural competency in food shopping choices.”