Painting by numbers: coloring in the landscapes of despair

A new study published in JAMA offers indisputable evidence that deaths of despair from alcohol, suicide and drugs, connected to economic factors, have ravaged the working age population in the U.S. during the last four decades

The darker side of the conversation is the way that the powers that be, for lack of a better phrase, have a tendency to blame the victim, the patient, or the immigrant for all of the nation’s troubles – or, for all the Rhode Island’s troubles.

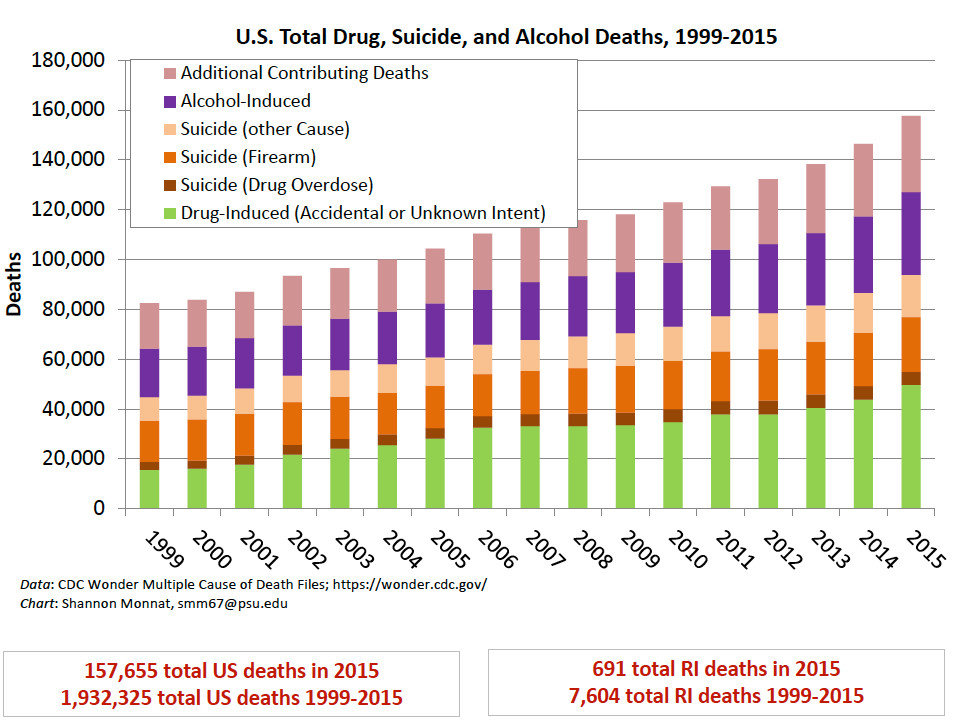

PROVIDENCE – For the past three years, ever since first becoming aware of the groundbreaking research conducted by Syracuse University sociologist Shannon Monnat that was published in January of 2017, focused on the deaths of despair, documenting the high mortality rates from alcohol, suicide and drugs, particularly for the demographic of young people between the ages of 25-34, that issue has become a constant drumbeat in reporting by ConvergenceRI.

Monnat’s research showed, analyzing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention mortality statistics for 2010-2014, that Rhode Island had one of the highest rates of mortality in the nation for non-Hispanic white residents between the ages of 25-34, comprising 59.8 percent of all deaths in that age grouping, caused by alcohol, suicide and drugs, a startling high number.

[ConvergenceRI brought Monnat to Rhode Island on Oct. 27, 2017, to deliver a talk on “The Landscapes of Despair.” See links below to a series of ConvergenceRI stories.]

In her talk, Monnat challenged policy makers to address the broader context of the problem, which she said defied many of the traditional policy responses: “We can’t arrest our way out of this,” she said. “We can’t Narcan our way out of this. We can’t treat our way out of this.”

The choices being made by individuals, she continued, did not manifest themselves in a vacuum; they were interconnected. “They exist within the context of larger social structures: family, the economy, educational institutions, health care systems, political systems, and community,” Monnat said.

Monnat’s research, however, did not seem to resonate with many Rhode Island policymakers, decision makers, and health system executives.

Time and again, when ConvergenceRI posed questions about strategies to confront the “diseases and deaths of despair,” the questions were deflected, including by members of the Governor’s Task Force on Overdose Prevention and Intervention, as being “tangential” to the work being undertaken.

Overwhelming, data-driven evidence

Now, a new study, published by JAMA [the Journal of the American Medical Association] on Nov. 26, 2019, entitled “Life Expectancy and Mortality Rates in the United States, 1959-2017, by Steven H. Woolf, MD, MPH and Heidi Schnoomaker, MA Ed., in the form of a “special communication,” provides a devastating look at how the diseases and deaths of despair have resulted in decreases in life expectancy at birth, a common measure of a population’s health, in the U.S. for three consecutive years.

Following the study’s release, one of the nation’s leading recovery community advocates wrote to ConvergenceRI, calling attention to the new study, acknowledging ConvergenceRI’s role in attempting to make the deaths of despair front-and-center in the conversation, saying: “This has been your rallying cry for some time now.”

The national recovery advocate included in the email a number of selected quotes from The Washington Post story about the JAMA study, published on Nov. 25, with the headline: “There’s something terribly wrong; people are dying young at alarming rates.”

• “The state with the biggest percentage rise in death rates among working-age people in this decade – 23.3 percent – is New Hampshire, the first primary state.”

• “Increasing midlife mortality began among whites in 2010, Hispanics in 2011 and African Americans in 2014, the study states.”

• “People are feeling worse about themselves and their futures, and that’s leading them to do things that are self-destructive and not promoting health.”

In addition, the national recovery advocate included another selected quote from a story written by reporter Melissa Healy for The Los Angeles Times, under the headline: “Suicides and overdoses among factors fueling drop in U.S. life expectancy; it’s official, Americans are dying much sooner in life.”

• “The states that experienced the steepest hikes in premature deaths were New Hampshire, West Virginia, Ohio, Maine and Vermont.”

In ConvergenceRI’s opinion, the best nut paragraph reporting on what the study found was in The Washington Post story by Joel Achenbach:

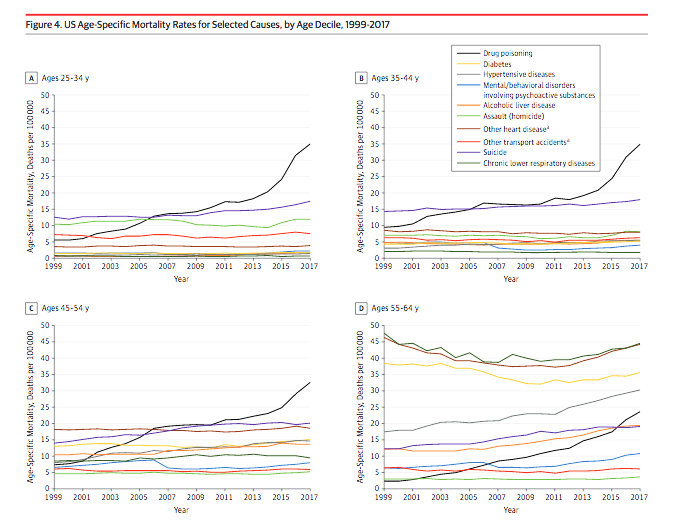

• “Despite spending more on health care than any other country, the United States has seen increasing mortality and falling life expectancy for people age 25 to 64, who should be in the prime of their lives. In contrast, other wealthy nations have generally experienced continued progress in extending longevity. Although earlier research emphasized rising mortality rates among non-Hispanic whites in the United States, the broad trend detailed in this study cuts across gender, racial and ethnic lines. By age group, the highest relative jump in death rates from 2010 to 2017 – 29 percent – has been among people age 25 to 34.” [emphasis added]

Just the facts

It is worth reading the entire JAMA study, for those that still actually read documents. For those that may not read, here is a brief synopsis of the study and its findings:

“Life expectancy at birth, a common measure of a population’s health, has decreased in the United States for three consecutive years.

“This has attracted recent public attention, but the core problem is not new—it has been building since the 1980s.

“Although life expectancy in developed countries has increased for much of the past century, U.S life expectancy began to lose pace with other countries in the 1980s.

“By 1998, [U.S. life expectancy] had declined to a level below the average life expectancy among Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries.

“While life expectancy in these countries has continued to increase, U.S. life expectancy stopped increasing in 2010 and has been decreasing since 2014.

“Despite excessive spending on health care, vastly exceeding that of other countries, the United States has a long-standing health disadvantage relative to other high-income countries that extends beyond life expectancy to include higher rates of disease and cause-specific mortality rates.

“This Special Communication has two aims: to examine vital statistics and review the history of changes in U.S. life expectancy and increasing mortality rates; and to identify potential contributing factors, drawing insights from current literature and from a new analysis of state-level trends.”

The evidence and the findings

The JAMA study examined longitudinal trends in life expectancy at birth and mortality rates [deaths per 100 000] in the U.S. population.

The life expectancy data was drawn from 1959-2016 data and cause-specific mortality rates for 1999-2017, drawn from the CDC database.

The analysis focused on midlife deaths [ages 25-64 years], stratified by sex, race and ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geography for all 50 states.

The findings included:

• Between 1959 and 2016, U.S. life expectancy increased from 69.9 years to 78.9 years but declined for three consecutive years after 2014.

• The recent decrease in U.S. life expectancy culminated a period of increasing cause-specific mortality among adults aged 25 to 64 years that began in the 1990s, ultimately producing an increase in all-cause mortality that began in 2010.

• During 2010-2017, midlife all-cause mortality rates increased from 328.5 deaths/100 000 to 348.2 deaths/100 000. By 2014, midlife mortality was increasing across all racial groups, caused by drug overdoses, alcohol abuse, suicides, and a diverse list of organ system diseases.

• The largest relative increases in midlife mortality rates occurred in New England [New Hampshire, 23.3 percent; Maine, 20.7 percent; Vermont, 19.9 percent] and the Ohio Valley [West Virginia, 23.0 percent; Ohio, 21.6 percent; Indiana, 14.8 percent; and Kentucky, 14.7 percent].

The increase in midlife mortality during 2010-2017 was associated with an estimated 33,307 excess U.S. deaths, 32.8 percent of which occurred in four Ohio Valley states.

The response

The weight of evidence from the study suggests the need to change the focus of the response to what has been termed the opioid epidemic and look at the deaths of despair from a broader population health context.

Monnat, who is currently the Lerner Chair for Public Health Promotion and Associate Professor of Sociology at Syracuse University, wrote in a brief email to ConvergenceRI over the Thanksgiving weekend: “Overall, the findings are not surprising. The fact that rising mortality rates are not restricted to just one or two causes of death reveals that there are systemic problems in U.S. society,” she said.

Are Rhode Island’s policy makers prepared to make changes in strategy, in response to JAMA’s data-driven evidence, focusing on a broader public population health context? Good question.

ConvergenceRI reached out to a number of Rhode Islanders involved in recovery efforts to get their response to the new JAMA study and what it might mean for future strategic policy directions.

Going upstream

“I think the story is all about going upstream, looking at economic and social determinants and not just trying to put our fingers in the dike,” said the national recovery advocate. “Resourcing effective prevention, treatment and recovery support programs will always be necessary, but the job is much larger, and we need to think about how to heal generations and provide more opportunity for everyone.”

How people cope with stress

Peter Simon, a retired pediatrician and epidemiologist at the R.I. Department of Health, offered a response not in direct reaction to the JAMA study but to the broader intersection of public health and population health: “I would bet there are three or four place-based factors, social and environmental, that explain the increasing deaths from diseases of despair, coupled with economic disasters that have been occurring in some places over the last 40 years.

Simon continued: “Then there are the psychological differences in the way people cope or do not cope with stress. Jonathan Haidt’s recent book, The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure, is exploring this, and I just finished reading the first two chapters.”

Further, Simon said: “More help bringing the findings of these studies [and the continuing research by Shannon Monnat] is a great role for ConvergenceRI. What are the ways these social and environmental forces can be mitigated? How can we change the way we spend on things that actually will impact on the quality and length of our lives?”

Simon then attempted to connect the dots between the findings of the JAMA study and the current efforts being undertaken by the state in its takeover of the Providence public schools. “My unrelated reaction is more with the difference between the way epidemiologists examine data and those that consider themselves critics of public education,” he said. “I am hoping that Dr. Patrick Vivier, [director of the Hassenfeld Child Health Innovation Institute], will soon tell us more about school achievement in Rhode Island, using public health analytical tools.”

A significant driver

Rebecca Boss, the director of the R.I. Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals, and co-chair of the Governor’s Task Force on Overdose Prevention and Intervention, said:

“We know that the opioid epidemic has been a significant driver of this trend, and we need to continue to respond with a multifaceted approach that includes prevention, rescue, recovery and treatment. This research just highlights the fact that we cannot reduce our focus on this issue.”

Boss continued: “We also know that rescue, recovery and treatment strategies aim for and have immediate impact on overdose death rates. However, if we are to have a long-term impact on this trajectory, we know our emphasis on prevention as a strategy is the right direction. We need to reach children and adolescents and impart to them the skills they need to deal with life and stress and feelings of despair, and teach them to make healthy choices and avoid substance use. To the extent that we can do that, we can begin to turn this trend around.”

Further, Boss said: “Of course, other factors are also causing a decline in life expectancy, and it’s important for Task Force members to be aware of them. None of the factors that are causing this trend work [in] isolation, so as we know more about the causes, we will be in a better position to respond.”

Issues of gender

Ian Knowles, the program director at the Rhode Island Communities for Addiction Recovery [RICARES], one of the state’s leading advocacy voices for the recovery community, said that the findings of the JAMA study underscored the failed attempts for the last 100 years to control substance misuse.

Knowles said: “Our ineffective national solution for the last hundred years has been an attempt to control substance misuse. From the alcohol prohibition of the 1920s, to the continuing national War on Drugs that started in 1970, the policies have ignored the complex nature of addiction – whose underpinnings are, at the least, biological, chemical, neurological, psychological, medical, emotional, social, political, economic and spiritual.”

Knowles continued: “The operationalization of the national policy has resulted in a simplistic, but politically useful, focus on the control of a specific substance at a particular time, e.g., marijuana, alcohol, crack cocaine, and now opioids.”

Further, Knowles said: “The JAMA study points to the need to address social determinants of health as a central part of addressing the addiction crisis. It also shows that our present isolation of opioids from alcohol and suicide is artificial.”

Digging deeper into the actual findings of the study, Knowles said: “A particularly troubling finding is the larger relative increase in the rate of risk of drug overdose, suicide and alcohol-related liver disease for women, compared to men. In Rhode Island, gender-specific addiction treatment programming continues to be sparse. We continue to stress the need for more treatment and recovery programming for women, such as women’s certified recovery houses, if we want to stop the intergenerational transmission of addiction and trauma.”

Setting the stage for convergence, or avoidance

This week, Gov. Gina Raimondo will preside over two big economic “success” stories. On Thursday, Dec. 5, the ribbon-cutting ceremony at Gotham Greens greenhouse in Olneyville, a state-of-the-art production facility slated to grow hydroponic lettuce and herbs such as basil for the burgeoning food market in Rhode Island [and which some have predicted can be easily converted to the much more lucrative crop of growing hemp and marijuana in the future].

On Monday, Dec. 2, the Governor will be joined by Pawtucket Mayor Donald Grebien to announce what has been billed as a “major economic development announcement regarding the City of Pawtucket,” which is predicted by some observers to involve the potential redevelopment of McCoy Stadium into a professional soccer venue, using federal opportunity zone tax incentives.

And, on Saturday, the Rhode Island Foundation will convene its second “Make It Happen” event of the decade, focused on making public education in Rhode Island a world-class enterprise.

All three are promising developments, for sure. But the darker underside, the hidden linkage, the connective tissue, to all three events, are contained in the findings of the JAMA study: how the diseases and deaths of despair, tied to economic disparities and health inequities, despite the tremendous expenditures of the U.S. health care delivery system and investments in the U.S. public education system, are overwhelming the workforce population, particularly the ages between 25-34.

Ignoring the deaths of despair and deflecting conversations about their realities in Rhode Island will only tend to exacerbate the conditions of the diseases.