Parsing the politics of problem definition

In health care, in education, too many folks think that because they have a hammer as a tool they need to keep looking for a nail to hit

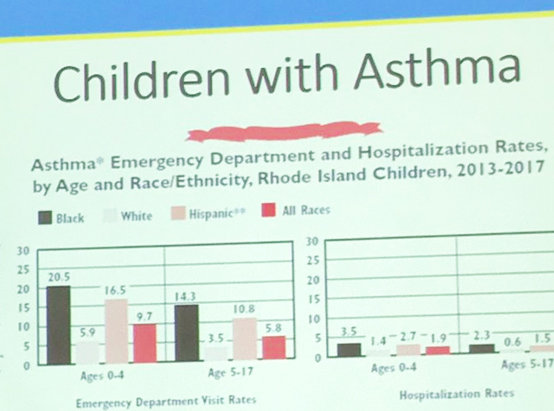

For instance, if you want to look at the problem of chronic absenteeism by students and teachers in Providence public schools, it requires looking at the causes of asthma, which is the third leading cause of hospitalization for children under age 15 and one of the leading causes of school absenteeism, according to the 2019 Rhode Island Kids Count Factbook.

In education, as the inexorable forces of politics and big money behind pubic education reform push for more charter schools, more corporate-driven personalized learning platforms, more teaching that is focused on results tied to standardized testing results, what say do students have in the process? A more important question: what are the tools and skills students need to succeed in the 21st century economy? How do students’ voices become heard in the process?

PROVIDENCE – I remember the day like it was yesterday. Outside the Brown Bookstore, in large bins, stacks of books had been placed on sale. I started to look through the piles, looking for nothing in particular, when I came across The Politics of Problem Definition: Shaping the Policy Agenda, edited by David A. Rochefort and Roger W. Cobb. I think I paid $4 for my copy of the book.

Later that day, I started to read the introduction and perhaps the first couple of chapters. I quickly realized how much it helped to explain what I had been experiencing as a small player in the large field of child health policy in Rhode Island.

More recently, I found myself thinking about the picture of our Providence Mayor Jorge Elorza, holding his son in his arms at work, and being attacked from all sides for exploiting his power to avoid the cost of child care.

What was the outrage about?

It was not so much the outrage of those criticizing him for taking advantage of his position to avoid the costs of paying for childcare that struck me as excessive and misplaced.

What upset me more was the fact that this all took place in the midst of the current debate over the state takeover of the “failing” Providence Public Schools.

Everything I have learned in 40 years working in public health – working with families, many of whom I saw on Tuesday nights at the health centers in Providence, from national discussions of the importance of early care and education on the growth and development of children, and from trying to build a public health response to childhood lead poisoning – suggested that the politics of “problem definition” had reared its head again in Providence’s search for a better public education system.

Where in the carefully framed analysis by the folks from Baltimore at Johns Hopkins was the information about how few children in Providence entered kindergarten ready to learn? Perhaps they were prevented from including this information or even questioning the kindergarten teachers about what their students lacked that explained the poor achievement patterns documented by testing in the third grade.

Where are the advocates for early child care and education in this debate?

Why did the Providence Public School Department discontinue the PALS assessment at kindergarten entry that predicts which children will fail to read well by third grade? [See Editor’s Note below.]

Why aren’t teachers calling for increasing the number of Head Start slots in Providence from 75 that exist today for 2,500 children entering kindergarten each year?

The answer, of course, can be found in the politics of problem definition.

Peter Simon is a frequent contributor to ConvergenceRI.

On Thursday, Oct. 17, from 5:30 to 8:30 p.m., at its annual meeting at the Rhode Island Shriners’ Imperial Ballroom in Cranston, the Rhode Island Public Health Association board of directors will present its 2019 Lifetime Achievement Award to Dr. Peter Simon, retired pediatrician and epidemiologist, for his significant contributions to advance the public’s health, recognized by his public health peers.

Editor’s Note: Phonological Awareness Literacy Screening, or PALS, provides a comprehensive assessment of young children’s knowledge of the important literacy fundamentals that are predictive of future reading success. Advocates of PALS believe that early literacy screening is the key to providing effective literacy instruction and preventing future reading problems. [See link below to the details of what is contained in the PALS screening.]

The decision to drop the PALS screening was apparently made during the Race To The Top initiative, according to Simon.

In 2013, Simon and five colleagues published an article in the journal Pediatrics on May 13, 2013, “Elevated Blood Lead Levels and Reading Readiness at the Start of Kindergarten,” which was the first study to show that reading readiness early in kindergarten is independently associated with blood level levels well below 10 mg/dL Further, the results of the study suggest that lead exposure may have a larger impact on urban education than national estimates suggest.