Promoting mental wellness as a way to repair harm

The Youth Restoration Project will hold its third annual symposium on May 18

“Opioids may have been the spark, but a spark needs kindling in order to ignite,” Monnat said. “This kindling is decades of economic restructuring, rising income inequality, social disconnection and loss of social cohesion, an emphasis on consumption to satisfy us and give our lives meaning, our demand for quick fixes to medical ailments, and an economic regime that emphasizes the market and maximizing shareholder value over collective societal well-being.”

PROVIDENCE – When managing director Julia Steiny convenes the third annual Youth Restoration Project Symposium on Friday, May 18, from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. at the Rhode Island College Student Union Ballroom, it will capture many of the ways in which the groundbreaking initiative has evolved on its path toward cultivating relationships and building community during the last few years. [See links below to ConvergenceRI stories, “Endorsing, embracing restorative practices as a community,” and “Restoring hope, repairing harm, upholding accountability.”]

The theme of the gathering is: “Imagine what safety feels like,” with the goal of leaning how to talk [and listen] about how to build trust and disarm conflict in our communities and schools.

Victor Capellan, superintendent of Central Falls schools, will serve as the host of the symposium, which will feature two special guest speakers: Lauren Abramson, founder of Restorative Response Baltimore, and Carolyn Boyes-Watson, director of Suffolk University’s Center for Restorative Justice.

For the uninitiated, as part of the process of restorative practices, there are four basic principles of “agreement” that guide the conversations and conferences around building relationships, maintaining community, and repairing harm.

• We ask questions to understand or clarify, and we listen patiently for answers.

• We take turns speaking, so that each person gets heard, without interruption, waiting your turn, and listening to each person.

• We use “I” statements, speaking about what you saw, what you felt, and what you did did or want to do, avoiding “you” statements that accuse

• We stick to the facts, agreeing to tell your story of what happened, referring to the behavior and the person.

The differences between mental wellness, mental illness

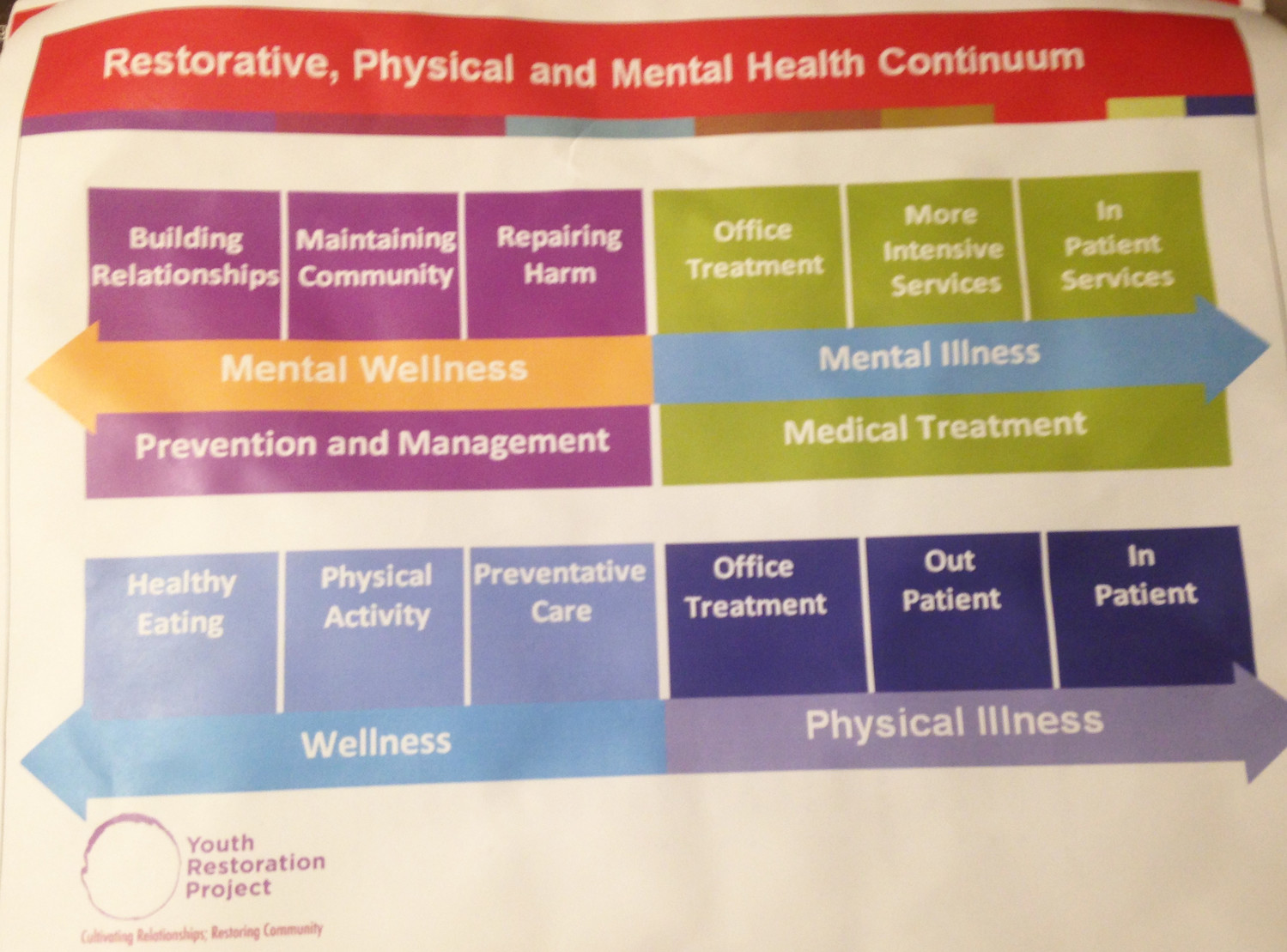

When ConvergenceRI recently sat down to talk with Steiny in advance of the symposium, she shared a graphic showing of what was called “the restorative, physical and mental health continuum,” drawing a distinction between mental wellness, with a focus on prevention and management, versus mental illness, with a focus on medical treatment.

Under the mental wellness quadrant, she explained, there were the activities of restorative practices in building relationships, maintaining communities and repairing harm; in contrast, under the mental illness quadrant, there were office treatment, intensive services, and inpatient services.

Similarly, there was a quadrant for wellness, with the focus on healthy eating and preventative care, in contrast to the physical illness quadrant, which included office treatment, outpatient and inpatient care.

And, as a backdrop for the context of the work being done by the Youth Restoration Project, on the back of the graphic drawing the distinctions between mental wellness and mental illness, is a fact sheet from the Mental Health Association of Rhode Island, which stated:

• One in five children ages 6-17 has a diagnosable mental health problem

• One in 10 children has a significant functional impairment

• An estimated 34 percent of Rhode Island children who needed mental health treatment or counseling in the past 12 months did not receive it.

“Everybody knows what it is to be sick,” Steiny said, explaining what the continuum graphic sought to demonstrate. At the same time, she continued, “Everybody knows [what wellness is] – that we shouldn’t smoke cigarettes, we should go to the gym and exercise, that we should take care of our health [needs].”

And, while we may “know” in our heads all these things about wellness, Steiny explained, “We don’t necessarily do them.”

The problem, Steiny said, “is that when we say mental health, what we usually mean is mental illness” – which often involves the post-diagnosis world of drugs, treatment and inpatient care.

By the time you get to hospitalization and drugs, Steiny continued, “You’ve just spent your top dollar, ironically, without having any [community] intervention system in place for all the screening that you’ve done for depression.”

“What we don’t talk about is mental wellness,” she concluded, drawing parallels with the challenges faced by the ongoing work with restorative practices.

So, Steiny asked ConvergenceRI: “What are the things that will help to support mental wellness? You often focus on it,” she added.

“Convergence? Conversations? Engaged communities? Connectedness?” ConvergenceRI answered

“Connectedness,” Steiny said. “We don’t have a lot of conventions or ways to stay connected in the world.”

When it comes to misbehavior in schools, Steiny explained, “If a kid is flagging, we often try to fix the behavior, instead of getting the root of the problem.”

A student could be “flagging” for a number of reasons, Steiny continued, that they don’t understand the expectations, that they don’t have the skills to meet them, or that they are having emotional troubles and are asking for help by seeking attention.

All too often, the response is to say: that kid wants to piss me off, taking the behavior personally. Through the Youth Restoration Project, Steiny continued, we sit down with the student, the parents, the teacher, everybody, to try and get at the root of the problem.

Reconditioning the social soil

For Steiny, there is a basic recognition that goes with the work of restorative practices: “You can’t give kids a personality transplant,” she said.

“We have to cultivate the change, to figure out what conditions are creating the mess, the root cause, and then go back and recondition the social soil,” Steiny said, adding that she was a big gardener.

One of the concepts that we teach in restorative practices, Steiny continued, is to ask: “What does it look like when we’ve got it right?”

Tracking the data

Over the next year, the results of the data tracking the work of the Youth Restoration Project will be analyzed, Steiny said.

She expressed some concern about what the data may show about the efforts to build community through conferencing and restorative because, as Steiny put it: “That may turn out to be the bigger lift [than we anticipated]”

Over time, as part of the learning process, Steiny continued, “We have radically changed our procedures. Just our presence has raised the water level of information about what restorative practices are; as the water table goes up, people have more understanding and more willingness to come to table and listen.”

Violence as frustrated attachment

When asked about how the work on restorative practices and repairing harm connects with violence, Steiny cited the work of author Susan Johnson, who studied the children of incarcerated parents, and concluded that “violence was frustrated attachment,” according to Steiny.

“That phrase came singing out of the blue to me, and it became one of my most steady anchors in the work that I’ve continued to do,” Steiny said. “It is all about attachment. When you are working in the repairing harm world, you’re basically focused on re-attaching.”