The coming health care revolt

What is the value of Clinica Esperanza, a mostly volunteer-run health care clinic, providing the safety net for the safety net, with low-cost care, serving a complex patient population and achieving great outcomes?

PROVIDENCE – The economic fragility of the health care delivery system in Rhode Island has been exposed once again by the looming strike by the United Nurses and Allied Professionals union against Lifespan at Rhode Island Hospital and Hasbro Children’s Hospital, scheduled to begin on Monday, July 23, at 3 p.m., unless federal mediators can bring the two sides together at the bargaining table to reach a last-minute accord, an unlikely occurrence given that Lifespan has already paid a $10 million fee to an agency for replacement nurses.

The three-day strike, followed by a fourth day of a lockout, underscores the economic difficulties of running a hospital when the business model no longer works and the realities of ever-increasing medical costs come crashing down on Lifespan, the state’s largest health system.

The battle has been portrayed in the news media as a conflict between the union, which represents some 2,400 nurses and health care professionals, and management at the hospital system, centered around how much Lifespan is willing to invest in maintaining the high quality and staffing for patient care at the bedside.

Lifespan’s response, as reported by The Providence Journal, is that the health system has paid $10 million to a temporary staffing agency, which enables the agency to mobilize people, make travel arrangements and secure accommodations. [That seems to be a helluva lot of money to invest in the consequences of a three-day strike and one-day lockout, in ConvergenceRI’s opinion.]

The questions are: was there a better way to invest that money? And, now that the money has been spent, who will bear the brunt of paying for those costs – the hospital administrators, the nurses or the patients?

The political realities of the strike drive home a stubborn fact: in today’s health care delivery system, nurses, not doctors, are most responsible for the day-to-day operations at both inpatient and outpatient settings, and they want to be paid accordingly for the value of their work; nurses are seldom rewarded with any shared savings achieved in population health outcomes that result from their work.

But the deeper conflict – call it a chronic disease of the health care delivery system, which some have called a market of wealth extraction – is the fact that the safety net for the safety net is being eroded and corroded, further threatening the health and well-being of all Rhode Islanders.

Clínica Esperanza, a nonprofit, mostly volunteer-run community health center in Olneyville, serving those without health insurance and many of the most at-risk, vulnerable Rhode Islanders, is seeing more and more uninsured Rhode Islanders seeking care. As many as 10 patients are turned away on a daily basis from the nurse-run, Clinica Esperanza/Hope Clinic ER Diversion Project [CHEER] walk-in clinic.

Clinica Esperanza may be forced to limit services or close its doors because of an inability to raise enough resources from the philanthropic and corporate community in Rhode Island to cover its basic operations, despite mountains of positive data that prove its value in reducing costs to the overall system of care and improving patient outcomes.

I hope you can hear me shouting

Dr. Annie De Groot is angry. The founder and volunteer medical director at Clínica Esperanza, which translates as Hope Clinic, asked plaintively in one of a number of emails sent to ConvergenceRI: “I hope you can hear me shouting. It’s not right, Richard. It’s NOT RIGHT.”

“I am going to throw down the gauntlet,” De Groot wrote. “This [lack of financial support] is not only short-sighted, but it’s cruel. We deprive our neighbors of good health. Why?”

Because, she continued, “The problem that is right in front of us is sometimes the hardest to deal with: there are still a lot of people who are uninsured and have no access to health care.”

The financial reality is dire, according to De Groot. “Clínica Esperanza is about $80,000 short of meeting our goals for funding for this year, and we’re only halfway through.”

I have no idea where I am going to make up that deficit,” De Groot admitted candidly. “I want to keep the clinic doors open. I give out of my own pocket. My company also contributes. Our generous volunteer physicians take time out of their lives to volunteer, but they also find [and give] money to keep the doors open.”

What follows are excerpts from a series of emails, in De Groot’s own words, which tell the story about what is happening, followed by testimony offered in direct support of the work being done by Clínica Esperanza.

These emails capture De Groot’s frustration about her inability to convince the beneficiaries of the clinic's work to step up to the philanthropic plate. Consider her lengthy emails to be the unwritten, untold story behind the health care crisis in Rhode Island. It is one that threatens to spark a health care revolt.

Penny-wise and pound-foolish

De Groot writes: In a nutshell, funding for public health, for the uninsured, for the poorest of the poor, is going from bad to worse.

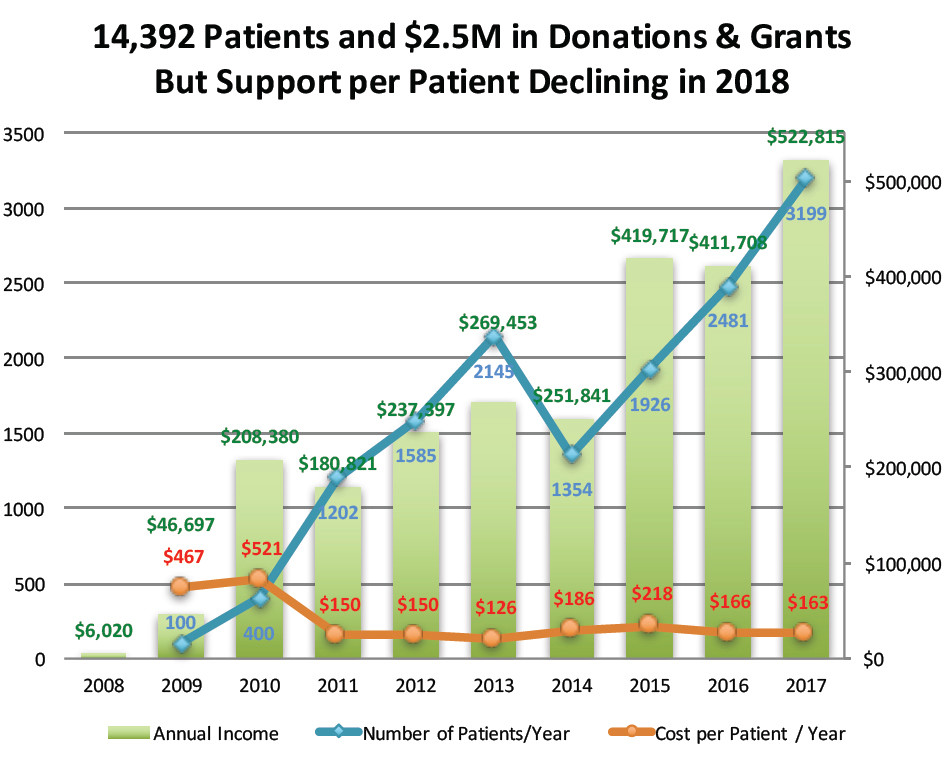

We have about $160 per patient per year available to take care of our more than 3,000 uninsured patients. That is a miniscule amount, and the problem is we’re getting less and less from our funders and may be forced to cut back and/or close.

Take the amount of funding we were just promised from the Community Development Block Grant [CDBG] from the city of Providence. We were allocated $21,000 in funding for next year. This is a nearly 25 percent decrease in funding since last year, while the number of our patients keeps going up by more than 30 percent per year on average.

CDBG funding pays only a part of the cost per patient, but the share is getting ridiculously small. The amount has gone from $11 per patient [about 7 percent of our costs] to less than $5 per patient [or about 4 percent of our costs]. Other funding sources are also declining or flat.

Here are some numbers to consider:

• Percent of uninsured Providence patients seen in the clinic last year: 80 percent.

• Percent of the clinic's annual budget provided by Providence: 4 percent.

• Percent increase in the number of patients seen year over year: 34 percent.

• Percent increase in CDBG funds for Clinica Esperanza year over year: 1 percent.

And, despite the lack of funding for our services, the clinic does a great job.

Just looking at diabetes: of 150 patients with diabetes, some 80 percent, or 120 of the patients, have a HBA1C [a test which measures a patient’s average level of blood sugar over the past two or three months] test scores below 9 [not everyone adheres to treatment despite our best efforts].

That’s a number with real value. Based on published performance measures, the value of that number of patients who have a HBA1C below 9 over one year is $112,080 [in avoided hospital costs].

• 70 percent of our hypertensive patients have their blood pressure under control. The value of the clinic's blood pressure control program is $156,541 [in avoided hospital costs].

• A publication by the clinic shows that the value of our ER diversion project [CHEER] is more than $500,000 per year [in avoided ED costs].

Question: Do the people of Providence and Rhode Island want to bear the cost of uncontrolled diabetes, and blood pressure in a large uninsured population, or does the city of Providence and the state of Rhode Island want to fund health care for the uninsured so that the cost of health care stays low and people stay in good health instead of getting sick and becoming an even greater burden for their families [and the government]?

It makes sense to support the successful work of the clinic: We are saving costs, lowering ED usage, and reducing inpatient care for the uninsured.

The ask

De Groot writes in another email: I have approached [local hospitals], my argument being that we save them ED costs for uninsured patients. They don’t appear to care. Perhaps that is because they use those “uninsured” costs [at the full rack rate] to offset their profits. Meanwhile they pay their CEO how much? More than $2.5 million total compensation. I can run the clinic serving more than 4,000 patients on just a fifth of [that salary]. Bottom line: It seems that local hospitals are not interested in helping out. There is still time to close the funding gap this year, and I hope that they will prove me wrong.

I also tried talking to the state of Rhode Island: what if we showed that we save funds, but the money we save doesn’t appear to exist. I had hoped that they would fund our work through a Pay for Success Pilot, but that idea was axed again by the R.I. General Assembly this year. That is penny wise and pound foolish, if you ask me.

Funding from the Rhode Island Foundation, Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Rhode Island, and CVS Health is generous [and we are grateful] but it is not enough. In fact, our costs and patient numbers continue to rise. One of the ironies about our work is that we cover half of the cost of health insurance for our staff, which is never covered by grants. Due to rising health care and other costs and increasing patient numbers, the clinic will be forced to cut back hours significantly [reducing the savings and, perhaps more important, shutting down desperately needed services for the poorest of the poor], or close outright this year. The trajectory of decreased funding is simply unsustainable.

Does it make sense to cut back funding for needed services as the need for services expands?

De Groot also asked in her email: If we truly care about “immigrants,” what better way to help then to provide them with quality health care?

What if the clinic closed? Someone [probably each one of the residents of Rhode Island through work or through federal programs will pay, through increased health care costs. Insurers or hospitals will have to find a way to cover the $500,000 more in ED costs, $112,000 more in diabetes costs, and $150,000 more in hypertension costs that the clinic is able to save the state by keeping its doors open.

What do you say to that?

Great outcomes, lower costs

In another email, De Groot writes: The cost of Medicaid for one new patient in 2015-2016 was about $5,000 [per patient per year]. The first two years of care are the most expensive. The cost of caring for a diabetic patient is probably about 2.7 times higher.

What is the cost of care for one patient at Clínica Esperanza Health Center? A “reasonable” cost, fully staffed and supported, would be about $1,000 [per patient per year].

When our patients do get insurance, they usually transfer to Medicaid and they continue to do well, saving thousands of dollars in Medicaid expenses per patient. Supporting our clinic to take care of the uninsured before they become insured could save the state as much as $4,000 in costs per year per patient.

Ask the Providence Community Health Centers: how do our patents do? We have checked on 40-60 patients who were transferred recently, and the overall cost of their care is lower than new Medicaid patients who have received our "pre-insured" care.

Looking at similar community health center organizations:

• CCAP grant and donation income in 2017: $26M. They serve 25,000 Rhode Islanders. That’s about $1,040 per client.

• EBCAP income in 2016: $27M dollars. Similar numbers.

• Clínica Esperanza Health Center income in 2017: about $500,000; that is a paltry $161 per patient in grant and donor support.

Look at the quality of care: The clinic's diabetes control measures approach national goals set for 2020, whereas most larger, government supported clinics do not achieve those goals.

Quality of care? Excellent. Value of investment? A huge return for every dollar of support.

Bridging the health access gap

In another email De Groot writes: Access to health care and information about health are two critical needs identified in Rhode Island, especially among Hispanics and low-income ethnic minorities.

Despite the advent of Obamacare, according to the R.I. Department of Health, 38-41 percent of Hispanics living in Rhode Island still lack health insurance. 41.2 percent of Hispanic/Latinos living in Rhode Island who are less than 65 years of age report having no insurance, 33.3 percent had not seen a doctor in the past year, and 31.3 percent are not able to afford to see a doctor.

In a recent survey of the neighborhoods served by the clinic, 36 percent of local Olneyville residents used the Emergency Room for primary care, and this rate has increased by 16 percent since 2016.

Lack of access to health care can endanger the health and well-being of individuals and their families. More specifically, in Rhode Island, lack of access to health care exacerbates the well-being of low-income, recent-immigrant Hispanic population, among whom rates of diabetes, high blood pressure and obesity are much higher than among whites or blacks.

According to the R.I. Commission for Health Advocacy and Equity Legislative Report, 2015, “In Rhode Island, diabetes disproportionately impacts … Hispanic adults, those who earn less than $25,000 per year, and those with less than a high school education. Rhode Island adults who primarily speak Spanish have twice the prevalence of diagnosed diabetes than adults who primarily speak English.”

Clínica Esperanza/Hope Clinic serves the large population of predominantly Spanish-speaking uninsured patients living in Olneyville.

Among patients at our clinic, 80 percent report earning less than $15,000 per year and 70 percent speak Spanish as their primary language.

Clínica Esperanza lowers barriers to health care and improves health literacy for these individuals by: engaging in health screens at a wide range of outreach locations in the community; providing free walk-in health care, and providing access to free longitudinal care clinics and chronic disease self-management programs. The clinic calls this the ‘Bridging the [Health Care Access] Gap’

Patients with chronic diseases who participate in the 'Bridging the Gap' program have registered significant improvements in their health, as measured by reductions in blood pressure and body weight, and improvements in their blood sugar measurements.

In addition to tracking their activities, and collaborating with stakeholders at the private, public, and nonprofit level, the clinic works with local community partners to develop an economic model to establish the value of health care provided by our clinic for the community. [De Groot wrote that she hopes to use this model to develop a "Pay For Success" structured transaction with the State of Rhode Island, to support the important “bridging the health care access gap” efforts that take place at Clínica Esperanza.

Our budget is now more than $500,000 per year. We raise these funds by writing grants and have been very successful. We keep our costs low by not having an Executive Director. I volunteer as Medical Director.

Despite our best efforts, this year we have not yet raised our $500,000 goal. We are at the halfway point. We will have more than 4,000 patient visits in 2018. My staff is stretched to the max. I am very concerned.

The view from the R.I. Department of Health

In response to questions from ConvergenceRI, the R.I. Department of Health offered the following statement of support for the work being done by Clinica Esperanza:

“Although the Affordable Care Act has reduced the uninsured rate in our state, many Rhode Islanders remain without health coverage and have limited access to services,” Joseph Wendelken, the communications spokesman at the agency, wrote. “As a free clinic, Clinica Esperanza provides essential and comprehensive medical care and preventive health services to low-income and uninsured people in Rhode Island.”

Further, the R.I. Department of Health also voiced support for the work Clinica Esperanza has done on prevention of chronic diseases and diabetes control measures:

Through its participation in the Rhode Island Chronic Care Collaborative (RICCC), Clinica Esperanza has also done tremendous work around quality improvement initiatives related to the prevention of chronic disease – specifically diabetes, heart disease, and stroke prevention,” Wendelken wrote.

For example, Wendleken continued, “Clinica Esperanza has redesigned the workflow within its practice to identify patients with undiagnosed hypertension or identify patients who are appropriate for referrals through the Department of Health’s Community Health Network into evidence-based, lifestyle behavior change programs, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Diabetes Prevention Program.

These quality improvement efforts improve the delivery of care and services provided to uninsured and low-income Rhode Islanders, and other vulnerable populations.

Connection to health equity

Wendelken also answered a question from ConvergenceRI about the relationship between Clinica Esperanza and the existing health equity zones in Providence, including one serving the Olneyville community.

“As part of their work to address the socioeconomic and environmental determinants of health in their communities, many of Rhode Island’s Health Equity Zones have established partnerships between clinical providers and other community-based HEZ Collaborative members,” Wendelken said, providing background and context. “They have also worked to improve access to evidence-based programs among HEZ residents, based on community needs.”

“Clinica Esperanza is a member of the Olneyville Health Equity Zone Collaborative and receives funding through the HEZ to provide Diabetes Prevention Program classes to its patients,” Wendelken continued. “The Olneyville HEZ also provides fresh produce from Farm Fresh Rhode Island’s Mobile Market to Clinica Esperanza’s DPP participants.”

The relationship to public health

ConvergenceRI asked Dr. Peter Simon, a retired pediatrician and associate professor for the practice of Epidemiology at the School of Public Health at Brown University, to weigh in on the importance of Clinica Esperanza in supporting the community health infrastructure in Providence, and the financial consequences of unmanaged diabetes to the entire health care system.

Simon wrote: “First, health care requires both linguistic and cultural competencies.” The investment in outreach and care management using bi-cultural trained community health workers, Simon continued, a strategy deployed by Clinica Esperanza, “means that barriers to access and follow-up are identified and addressed at the front end and cracks into which many would fall are avoided.”

Simon added: “Having pharmacy services as well as general medicine and lab services in one place make care coordinated as well.”

In terms of the financial importance of managing diabetes, Simon wrote: “Much has been written about the cost impacts of diabetes on health care. Many of the immigrants who come here and transition to our lifestyles and diets end up with Type II diabetes, which will lead to loss of vision, kidney failure and coronary artery disease, which are expensive to treat, and lead to disability, death and dissatisfaction.”

The ability to help a person with diabetes manage their blood sugar, Simon continued, “is only one aspect of treatment. Getting people to change their diets and level of fitness, good eye care, skin care and other components to a comprehensive management plan are challenging to all.”

Editor's Note: For those interested in contributing to the mission of Clinica Esperanza, volunteers are welcome to write the volunteer coordinator or sign up online at www.aplacetobehealthy.org. Contributions can also be made online or by mailing your support to CEHC, 60 Valley St., Suite 104, Providence, RI 02909.