To test, or not to test, is that the right question?

Inaccurate tests, a lack of testing supplies, armed militias blockading state capitols, and mixed messaging from the President have sowed confusion around testing policies – as well as what comes next in public health policy after testing

That dark comedic sketch has now become our current reality we are now living through, it seems. We could call it “The Deadly Experiment.”

So much is still unknown about the coronavirus and the way in which it attacks the human body. The first step in recovery is to admit what we don’t know, and further, to act prudently and to exercise caution.

The choices that we make as individuals, as family members, as residents in a neighborhood, may seem simple, but they represent potential life-and-death choices: Do I wear a mask? Should I dine out at a restaurant? Is going to a drive-in movie or a hairdresser worth the risk?

The idea that the town council in Narragansett is better informed to make decisions than the Governor and her team of public health experts strains credulity. Would you be willing to dive into a swimming pool without knowing if there was water in the pool?

Hopefully, there will be a vaccine developed to prevent the spread of the coronavirus within the next two years. But there is no inoculation to prevent the spread of stupidity.

PROVIDENCE – “Testing doesn’t give you cases. The virus gives you cases,” said Dr. Ashish K. Jha, the incoming dean of the School of Public Health at Brown University, appearing on Morning Joe on Friday, May 15.

Jha was pushing back against the latest in a series of misleading pronouncements on testing by President Donald Trump, who had staged an event in Allentown, Pennsylvania, on Thursday, May 14, at which he claimed that testing for the virus was “overrated.”

“We have more cases than anybody in the world,” Trump said. “But why?” the President asked rhetorically, and then answered: “Because we do more testing. When you test, you have a case. When you test, you find something is wrong with people. If we didn’t do any testing, we would have very few cases.”

Translated, ignorance is bliss – even if it can kill you.

Trump, still refusing to wear a mask when he appeared in public settings, continued on his rant, taking umbrage at criticisms about his apparent lack of leadership around testing. “So we have the best testing in the world. It could be the testing [is] frankly, overrated. Maybe it is overrated. But [whenever] they start yelling, we want more, we want more. You know, they always say we want more, we want more because they don’t want to give you credit.”

Translated, the President still sees himself as the biggest victim of the virus.

The context of the entire staged event in Pennsylvania was Trump’s blatant attempt to upstage and deflect coverage of the dramatic testimony by whistleblower Dr. Rick Bright, the former head of the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, or BARDA, before the House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Health on Thursday, May 14, at which Bright said: “If we fail to develop a national coordinated response, based in science, I fear the pandemic will get far worse and be prolonged, causing unprecedented illness and fatalities. Without clear planning and implementation of the steps that I and other experts have outlined, 2020 will be the darkest winter in modern history.”

In a tweet Friday morning, citing Dr. Jha’s comments, Dr. Leana Wen, who was also a guest on Morning Joe, said: “So obvious. But apparently we have to keep saying this. Testing is not the problem. It’s the key to solution.”

To which Dr. Peter Simon, a retired epidemiologist and pediatrician, replied on Twitter: “Testing if combined with contact tracing and isolation will be important, but who is going to contact trace and isolate low-income immigrant workers living in a densely populated neighborhoods? Who is going to house them, feed them, and keep them safe?”

A wrinkle in time

That Twitter dialogue between Jha and Wen and Simon provided a pithy, provocative snapshot in time, in the middle of May of 2020, capturing the conundrum of testing for the coronavirus in the midst of a pandemic, here in Rhode Island, in the U.S., and across the globe. As of Friday, May 15, there were 479 reported deaths in Rhode Island, 88,424 deaths in the U.S., and 308,046 deaths in the world. And counting.

Translated, the virus does not discriminate. It is an equal opportunity destroyer.

What is happening – or not happening – around testing, as many states prepare to slowly reopen after two months of shutdown, has emerged as a confusing linchpin of public health policy moving forward.

Among the key questions to ask – and to answer – include: Who can get tested? Who needs to get tested? How accurate are the tests in diagnosing the coronavirus? When should asymptomatic people be tested? How often should tests be performed on essential workers? How do you ramp up testing in vulnerable urban neighborhoods?

Intrinsic to asking and answering those questions is the importance of then sharing the results. Rhode Island has attempted, for the most part, to put an emphasis on transparency, particularly when compared to the behavior of some other states. In Nebraska, Iowa, and South Dakota, for instance, the Republican governors have decided to stop sharing the data results of testing at meat-packing plants and at nursing homes, because the data did not support their political positions. As a result, there is no apparent way for residents living near the facilities to better protect themselves from the spread of the virus.

Translated, data can get lost in translation on purpose, if that is the government’s intent, forcing residents to be flying blind through the fog of calculated misinformation.

Here in Rhode Island, the prevalent health inequities and disparities have been revealed, first by the initial testing protocols, which made it difficult for residents from many of the state’s most vulnerable communities to be tested, and then, once more testing sites were put into place, by the high number of positive tests from residents of color. However, such health inequities should not have been surprising. [See link below to story, “Connecting primary care to emergency care in a pandemic.”]

The high number of positive test results for COVID-19 for the state’s Latino population has raised a whole set of different questions for the state to answer around what actions and policies should be taken to address the disparities in a time of pandemic, which reflect the nature of high-density neighborhoods.

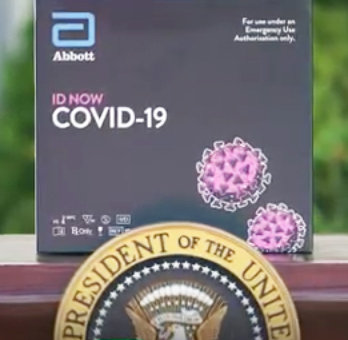

Finally, a great deal of confusion around testing policies has been creating by the changing, often contradictory messaging championed by the White House, which has run the gamut from “Anyone who wants a test can get a test” to “We have the best testing in the world” to “The Abbott [testing device] is perfect” to “Testing is overrated.”

That confusion has often been magnified in the news coverage by both the national and local media.

Asked and answered

ConvergenceRI consulted with a number of physicians on the front lines of health care in Rhode Island that are battling against the spread of the coronavirus, to ask them to provide some answers to the questions around what folks need to know about testing, as a kind of public service guide for the perplexed.

Here is a compilation of their answers. [They requested – and ConvergenceRI agreed – to allow them to speak off-the-record, without identifying them or their respective positions.]

“Here is a quick tutorial on testing, because neither the Facebook trolls nor the mainstream media can keep this straight,” the first physician explained.

• RNA-based nasal swabs have a turnaround time of 1-3 days. The testing detects active virus in the nose. The test is very sensitive, but can still miss 10-15 percent of the cases. It also seems to detect "dead" virus weeks after the infection has passed [that may or may not be contagious].

• Molecular nasal swabs have a turnaround time of 15 minutes. The testing detects virus in the nose. It may not be as sensitive as the RNA-based PCR testing. The Abbott “ID Now” testing device has been found to have high numbers of false negatives, according to a recent study by New York University, which found that the Abbott device had missed one out of every three positive samples.

The drive-by testing being done by CVS in a Twin Rivers parking lot in Lincoln, as well as at the White House, has been using the Abbott machines. The testing is conducted by using a nasal swab, which is then stuck into the Abbott rapid analyzer.]

[Editor’s Note: A new self-administered test, using a nasal swab, is now being deployed by CVS, with testing results available in two-to-four days, with the apparent intent to replace the problematic Abbott machine, according to news reports. According to the R.I. Department of Health, some 28,231 tests have been conducted at the Lincoln site using the Abbott machines, with 3,188 coming back positive – about 11 percent.]

• Antibody finger-prick testing has a turnaround of 15 minutes. Around the world, these products have a mixed success record, with numerous “crappy” products on the market and many false positive results.

• Antibody testing from blood drawn has a one-day turnaround. It captures a “historical” infection. It is “pretty accurate” for IgG [immunoglobulin] antibody tests. But it does not diagnose an acute infection. [The inherent problem is that a person really doesn't make antibodies of this type until at least five days after the symptoms start. And, no one yet knows if the presence of antibodies signals immunity or not from the virus, or for how long.]

In the first physician’s opinion, fingerstick rapid antibody testing should be avoided until more accurate tests are available and been proven to detect the virus more accurately. Further, the first physician continued, immunoglobulin testing for the presence of antibodies to the virus conducted in a real medical laboratory could provide population-level data for the virus prevalence, “but it is an ineffective way to diagnose the infection when a person's symptoms have just started.”

Making the best of a bad situation

A second physician, whose parent corporation is currently performing coronavirus testing, shared with ConvergenceRI concerns about the limited amount of testing supplies, such as swabs and reagents, and the lack of personal protective equipment for health care workers.

“Nasal swabs detect active virus, not immunity,” the second physician wrote to ConvergenceRI in an email. “One can be negative this week, and then get infected next week. Combine that with human nature, and suddenly you get people who are relieved to hear that they are negative, but then go to a party to celebrate – and get infected. If you’re lucky, you can find people who are shedding before they spread it to dozens of others.”

The difficulty with screening people without symptoms, the second physician argued, is just that – it is a screening, a snapshot. “On that particular day they probably didn’t have the virus, the second physician said. “What about next week?”

The confusion around testing, the second physician continued, created both by the President and by the news media, supporting the idea that if someone could obtain the test and be regularly tested, then everything would be OK, is problematic.

“Actually, no,” the second physician said. “One still needs to socially distance and try not to get infected in the first place, and hold out hope for a vaccine.”

Screening people without symptoms

When asked about the priorities around testing, a third physician told ConvergenceRI: “In a perfect world, we would test everyone – those with symptoms and those without, rapidly isolating people until they were better, and break the cycle of transmission.”

The third physician continued: “Who can do that draconian strategy? China can, and is doing so now in Wuhan to stamp out some hot embers [of virus transmission] before they take hold again.”

In the U.S., the public health strategy of “responding to the fire, then encircling it with contact tracing will eventually work,” the third physician said. But it may just take longer because people have the right to say “no” unless compelled by the courts. [The physician cited what happens with active case of TB, when a judge can force an individual to comply with treatment, but only if they represent an ongoing threat to others in the community. “One has the right to imperil their personal health, but not someone else’s,” the third physician explained.]

Where are we on the testing bell curve?

On Friday, May 15, Gov. Gina Raimondo shared her benchmarks and metrics for the indicators her administration will use to determine whether or not the state is “ ready” to move forward in the next phase of reopening. The indicators include:

• Hospital capacity – a green light if less than 70 percent of hospital beds are filled, and a red light if 85 percent of hospital beds are filled

• The rate of new hospitalizations – a green light if there are consistently 30 or fewer new hospitalizations daily, and a red light if there are consistently 50 or more new hospitalizations daily

• The rate of spread – a green light if where what is known as the R value is 1.1 or lower, and a red light if the R value is 1.3-1.5 or higher, and

• Doubling rate of hospitalizations – a green light if hospitalizations are doubling every 30 days or more, and a red light if hospitalizations are doubling every 20 days or less.

The bottom line, of course, gets back to calculations that are driven by testing results. At this juncture in mid-to-late May, a fourth physician described the situation as follows: we still don’t have enough tests, and we still don’t have enough personal protection equipment.

As a result, the fourth physician believes, the current public health strategy needs to remain focused on maximizing the “greatest good for the most people”:

• Reduce transmission among those at increased risk of dying

• Find any silent shedders who happen to work with those highest risk groups

• Protect the first responders and health care workforce to the greatest degree possible [stratified by those who serve the highest-risk populations].

The highest risk patients, the fourth physician said, were:

• Older patients, patients with chronic illnesses, and patients with immuno-compromised conditions [such as cancer survivors]

• Patients who are living in congregate settings, such as nursing homes, prisons, and group homes.

In addition, the fourth physician continued, when there are not enough tests to go around, there is a need to prioritize testing for the health care workers that are at highest risk.

In the fourth physician’s opinion, the prioritized workers should include: health workers at nursing homes, intensive care units, first responders, and health workers in primary care.

If I were “king or queen” of the forest

A fifth physician, when asked what changes if any they would make if they were in charge of the R.I. Department of Health, once the shortages in supplies and tests have been alleviated, spoke about changing the testing criteria from “those with symptoms” to include “regardless of symptoms.”

The priority list, from most urgent to least, would be:

• Test those with symptoms who are sick enough to be hospitalized

• Screen those at highest risk – with or without symptoms [at nursing homes, because that’s a tinderbox with a deadly outcome if you’re late to respond]

• Screen all staff at nursing homes – with or without symptoms, because they can silently shed to those highest-risk patients

• Test the general population that has symptoms [in order to actually intervene at a population level]

• Screen first responders that don’t happen to have symptoms [protect the workforce]

• Screen the general population that doesn’t have any symptoms but is interested in being tested

One of the problems, according to the fifth physician, is that the lack of testing capacity can leave some health care workers out in the cold, so to speak. While nursing home staff and ICU staff are now receiving testing under the current “priorities,” many staff at primary care facilities still cannot get tested if they are “without symptoms,” a situation confirmed by other physicians.

“There isn’t enough testing capacity to screen all of the health care workers yet,” the fifth physician said. “Part of the problem lays in lack of clarity in messaging, and historical missteps by more than a few in the health care business.”

In terms of specifics, the fifth physician said: “There hasn’t been enough personal protective equipment to protect nursing home staff. There are disparities in access to PPE among different types of health care workers, and now there are ‘different rules’ for screening the various types of health care workers.”

The fifth physician continued: “Nursing home medical assistants are being screened, but not clinical medical assistants. They talk. They want to know why there are differences. The answer lays in who they directly care for, not the honorable job description of being a “medical assistant” itself. They all deserve adequate PPE and clear communication. But right now there aren’t enough tests to screen all the entire health care workforce in the absence of symptoms.”

Who controls access to testing machines?

In a time of pandemic, with limited test kits and testing supplies and personal protective equipment available, it is still a political decision, it seems – who gets what, for how much, and when – on the distribution of testing kits and supplies.

Although ConvergenceRI was unable to confirm the situation, the allegation has been made that there has been a constant “tug of war” between CommerceRI and the R.I. Department of Health about which agency controls the decision-making of who was to receive the limited number of Abbott “ID Now” testing kits.

Moving forward

Much of the success of Rhode Island’s efforts to contain, to mitigate, and to reduce the harm from the coronavirus pandemic will depend on the important next step that follows widespread testing: contact tracing.

When asked about current resources and hiring related to contact tracing, Joseph Wendelken, the public information officer at the R.I. Department of Health, responded: “We have about 200 people doing contact tracing and case investigation [case investigations focusing on interviews with index cases].”

Wendelken continued: “We are using R.I. Department of Health employees, state employees, Rhode Island National Guard members, and contract staff for these positions.”

When asked about the need to hire new staff to ramp up contact tracing, Wendelken said: “At this time, we feel comfortable with the number of staff we have performing these roles. However, we are continuously monitoring our resources, and would adjust if the need arose.”

In densely populated urban neighborhoods, a sixth physician worried that the relatively small amount of contact tracers deployed by the state would be too small to be effective, particularly in neighborhoods where there are language and cultural barriers.

The physician told ConvergenceR that the importance of rapid testing, even if some of the results may not be accurate, is that it provides a level of tangible, believable evidence to prompt behavioral changes, a critical tool for someone who is deemed an essential worker, who carpools to work, who lives in a crowded living situation, from continuing to spread the virus, regardless of how severe that person's symptoms may be.