We cannot treat our way out of this

Why the remedies offered by the President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis won’t fix our problems

In turn, Sen. Josh Miller asked what happened to uninsured patients presenting at hospital emergency rooms in regard to medication-assisted treatment. The answer given was that uninsured patients might be given an initial shot of suboxone, with a prescription, but they would have to seek continuing care in a private setting outside of the hospital. It was explained that such uninsured patients were often referred to CODAC, for medication-assisted treatment with methadone.

The current caseload of counselors for methadone patients at CODAC is 45 per month, but some counselors have told Convergence that the caseload can exceed 50 per month. In turn, there is a high turnover among counselors, with difficulty in filling the positions with qualified and trained personnel.

SYRACUSE, New York – Since 1999, more than 600,000 people in the U.S. have died from drug overdoses, with opioids leading the way. Despite significant media and political attention and increases in spending to combat this epidemic, the death rate continues to surge.

There are many reasons for this, but one stands out. So far, strategies to address the opioid problem have focused almost exclusively on opioid supply reduction and treatment interventions rather than addressing the underlying social problems that got us into this mess. And now, the President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis offers us more of the same.

Last week the Commission released its final report laying out 56 recommendations to combat the U.S. opioid epidemic. “Prevention” approaches emphasize tightening physician prescribing, increasing law enforcement efforts, and reinvigorating the failed 1980s approach to teach kids to “Just Say No to Drugs.”

The one recommendation related to prevention in schools is an intervention to funnel high-risk youth into treatment. Ultimately, the Commission’s recommendations are dominated by a medical treatment model that emphasizes increasing funding for new pain drugs, increasing access to substance abuse treatment, including investments in medication assisted treatment, or MAT, and increasing access to the opioid agnostic – Naloxone [commonly sold under the brand name Narcan].

An emerging medical treatment and recovery industry

The Urban Institute reported that between 2011 and 2016, Medicaid spent over $3.5 billion on MAT, and that’s only a start. The cost of medical treatment for opioid use disorders over the next 10 years could be as high as $180 billion. At best, Big Pharma was complicit in the opioid overdose surge. At worst, they deserve the lion’s share of the responsibility for heavily marketing to and misleading physicians and the public about a product that was so easily abused.

The Commission is recommending restrictions on opioid prescribing, but this ignores the fact that heroin and fentanyl now cause more overdoses than prescription opioids.

At the same time, the Commission is encouraging funding for the development of new pharmaceutical solutions for pain relief and increasing the use of pharmaceuticals to treat opioid use disorders.

Under the Commission’s recommendations, the quick-fix medical model prevails, and Big Pharma will be handsomely rewarded for a problem it fueled.

To be sure, getting more people who need it into treatment and making Narcan universally available will save lives.

But, we need to get real with ourselves about the U.S. drug problem. We are not going to Narcan our way out of this. We are not going to treat our way out of this. The problem is bigger than opioids. The problem is bigger than drugs, altogether. Opioids are a symptom of much larger social and economic problems.

The spark and the kindling of the epidemic

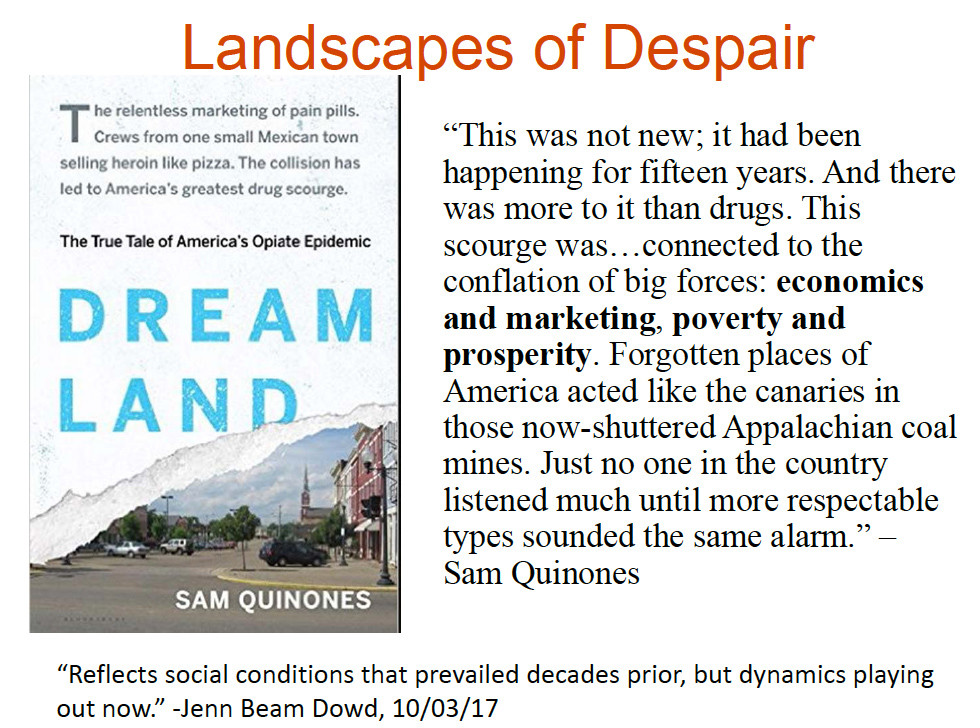

Opioids may have been the spark, but a spark needs kindling in order to ignite. This kindling, comprehensively described in must-read books by Sam Quinones, Brian Alexander, Victor Tan Chen and John Temple, is the result of decades of economic restructuring, rising income inequality, social disconnection and loss of social cohesion, an emphasis on consumption to satisfy us and give our lives meaning, our demand for quick fixes to medical ailments, and a neoliberal policy regime that emphasizes the market and maximizing shareholder value over collective societal well-being.

Income inequality is at an historic high, while the prime age (25-54) male labor force participation rate is at an historic low. Real wages have been stagnant for most workers for more than three decades; fewer jobs come with benefits such as health insurance, paid leave, and pensions. Young adults today have a much smaller chance of moving up the income ladder than in the past.

A large share of this country is truly struggling, and the chickens have come home to roost in the form of increasing rates of deaths of despair, including opioids.

Addiction is also a social disease

Public health experts are increasingly conveying the message that addiction should be viewed as a medical disease, just as we view other chronic diseases. If we accept that, then we also have to accept that, just as other chronic diseases have underlying social determinants, addiction is also a social disease.

“Addiction does not discriminate” is a sound bite that ignores the reality that overdose rates are highest among certain vulnerable groups [military veterans, victims of child and sexual abuse, people who have been incarcerated] and in economically distressed communities, particularly places that have experienced declines in job opportunities for people without a college degree.

From once vibrant manufacturing cities to the former coal country, labor market devastation has been the norm throughout many rural areas and small cities for more than four decades. Portsmouth, Ohio is a prime example of these trends.

In his book Dreamland: the True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic, San Quinones described Portsmouth as a place previously known for making things, with a once-thriving manufacturing base.

By the 1990s, the factories were long gone, replaced by big-box stores, check-cashing and rent-to-own services, pawn shops, and scrap yards. In today's Portsmouth, incomes are lower than in the 1980s and poverty, disability, and unemployment rates are high. As described by journalist Chris Arnade, Portsmouth now has the distinction of being the “pill mill capital of America,” with widespread generational opioid addiction, and where the emptying out of factories was followed by the emptying out of people and hope.

In these types of places all across America, jobs have been replaced by isolation, hopelessness, shame, and a loss of meaning. The American consumer has been complicit in this. The desire for lots and lots of cheap stuff helped push out small businesses, which found themselves unable to compete against the corporate giants.

Social decline

But economic decline is not the only factor driving our opioid problem. It is also deeply related to social decline – an era of individualism and personal responsibility, disinvestment in social safety nets, declines in social cohesion, and increased loneliness. We are simultaneously the most connected and disconnected society there has ever been. We have countless electronic ways to keep in touch with friends and family, but we spend less real time with them than in the past.

In a recent survey, 40 percent of U.S. adults report being lonely, up from 20 percent in the 1980s, more middle-age adults are living alone now than in the past, and, according to research by Penn State sociologist Ashton Verdery, a growing share of older Americans are kinless [with no living relatives]. Humans were not designed to be solitary. Being lonely makes us sad, stressed, and sick.

The pursuit of loneliness

A new report by the American Psychological Association shows that stress in America is at its highest level since polling began. How is this connected to the opioid epidemic? Research from Brookings Fellow Carol Graham shows that people who are hopeful and optimistic about the future are more likely to invest in that future and have better health outcomes, whereas those consumed with stress are less confident that such investments will pay off and sometimes engage in self-harming behaviors.

As the American Dream has eroded into a system where winners win big but losers fall hard, it is no wonder that people are seeking escape. But drugs aren’t the only escape. In fact, they’re not even the most common escape. High-calorie foods, smoking, and alcohol also offer temporary vacations from grief and despair, and they remain the three leading preventable causes of death in the U.S.

Suicide – the permanent escape – is also on the rise. Whether it’s via too much fast food, cigarettes, a bottle of vodka, or a needle, rising levels of stress, disconnection, and despair are killing us.

The Opioid Commission’s report barely acknowledges the broad social and economic problems underlying the nation’s opioid epidemic. These same big problems drove the crack epidemic in the 1980s and the meth epidemic in the 1990s and 2000s.

History tells us that once opioids have left the scene, another drug will come along, and there will be a new drug war to fight. Solutions to address these big problems are hard.

Combating today’s opioid epidemic [and tomorrow’s new drug epidemic] involves all of us reflecting on what kind of society we want. It requires us to reject a society where a small number prosper on the backs of the majority. It requires us to reject divisiveness and embrace support and connection. It requires us to reject quick fixes and copious consumption.

We are all complicit

We are all complicit in supporting a culture that gave rise to the opioid problem. The American cult of individualism is not a strength. It is a dangerous myth that encourages isolation and despair and keeps us from embracing the strategies necessary to end the opioid epidemic – livable wage jobs along the educational attainment continuum, a tax system that benefits the whole society rather than only the rich and powerful, and social, economic, and infrastructural investments in our communities.

The consequences of the U.S. opioid problem along with the broader problems of substance misuse and mental illness affect us all. Relegating prevention to a secondary status while we try to get a tourniquet on what many view as the pressing matter [the rising death toll] will ensure only that we need more tourniquets.

Until we are willing to invest time, energy, and political will into addressing the underlying causes of distress, despair, and disconnectedness, not only are we not going to stop the opioid epidemic but we are going to remain vulnerable to future drug epidemics.

Shannon Monnat (@smonnat) is the Lerner Chair of Public Health Promotion and Associate Professor of Sociology at Syracuse University.