What do the cost data on health care really tell us?

The dominant narrative about identifying and correcting the causes of rising health care cost trends in Rhode Island appears to have some gaping holes in the data analysis

Finally, protecting Rhode Islanders from the excesses of the fossil fuel industry remains a critical role for Rhode Island Attorney General to play as the state’s public health advocate.

PROVIDENCE – In the midst of two converging public health crises, the coronavirus pandemic and the recurring wave of gun violence, it is easy to get distracted – and to be swept away by click-bait sensationalism.

To report on apparent problems with health care data in Rhode Island, no matter how compelling the evidence, is not an easy task. [To be honest, I am struggling how best to do so.] Because digging deeper into the evidence found in the most recent data analysis could disrupt the dominant optimistic narrative around the proposed hospital mergers, consolidations, private equity buyouts, and the 10-year statewide health plan with a mission of making Rhode Island the healthiest state in the nation.

The good news first: we are slowly emerging from the depths of a severe national trauma. We have survived an attempted violent coup to overthrow the U.S. government, led by the former President; we have weathered the tragic deaths of nearly 600,000 Americans in the last 15 months from COVID-19, with millions afflicted with the virus. And, we have demonstrated remarkable resiliency in the recovery from enormous disruptions of our economy.

Translated, there is a strong desire to return to normalcy, whatever that means. Yes, the masks are finally coming off, thanks to the efficacy of vaccines and the efficiency of the Biden Administration in getting millions of doses of vaccines into American arms. [But, for those with a compromised immune system or for those who have not yet been vaccinated, the masks need to stay on.]

The messaging should be clear: Vaccines work. The underlying message should be equally clear: Government can and does work to provide for the common good. Those messages, however, can be hard to hear when there is so much noise, distortion, and misinformation, such as when Georgia Republican Congressman Andrew Clyde described the mob storming the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 as a “normal tourist visit.” Really?

Gun violence continues to ravage our urban neighborhoods; our mean streets have grown meaner. Gun violence is a symptom of the larger decay and disease caused by racial inequities and health disparities that the COVID pandemic has made all that much more visible. The preponderance of racial and ethnic disparities was one of the top takeaways from the 2021 Rhode Island Kids Count Factbook released last week. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “A virtual rite of spring.”]

“If you think the crumbling schools, administrator arrests, environmental racism in the Port of Providence, and vaccine inequity aren’t related to the gun violence in the city, then maybe you aren’t paying attention,” as State Sen. Tiara Mack tweeted.

The question is: How many deaths will it take before the R.I. General Assembly acknowledges that too many people have died – and to take legislative action?

The pendulum is shifting

When it comes to messaging around gun violence as a public health crisis, the political pendulum may be shifting. The recent court decision by a federal bankruptcy court in Texas means that one of the biggest perpetrators of false narratives around gun violence in America, the National Rifle Association, may soon face financial and legal dissolution, under a lawsuit brought by New York State Attorney General Letitia James. The judge ruled against the NRA, saying that it could not seek bankruptcy protection as a way to evade the pending lawsuit.

Where the two public health crises often collide and converge is in the hospital emergency room.

But, when we attempt to measure the ever-rising tide of health care costs, much like the rising waters on our coastlines caused by man-made, fossil-fuel driven climate change, the blame all too often gets put on the patient and the consumer: If only they made wiser choices.

Finding the truth hidden in health care data is hard work: “Americans like to be lied to,” the poet Robert Bly once told me, in a 1987 interview after a reading at the Iron Horse Café in Northampton, Mass. “We are still living in a Doris Day movie in which everything we do works out.”

When the numbers don’t add up

So it is with recent published health care data. In Rhode Island, the powers that be in the state’s health care industry have undertaken a massive research project to identify the causes of the rising costs in health care, know as the R.I. Health Care Cost Trends Steering Committee.

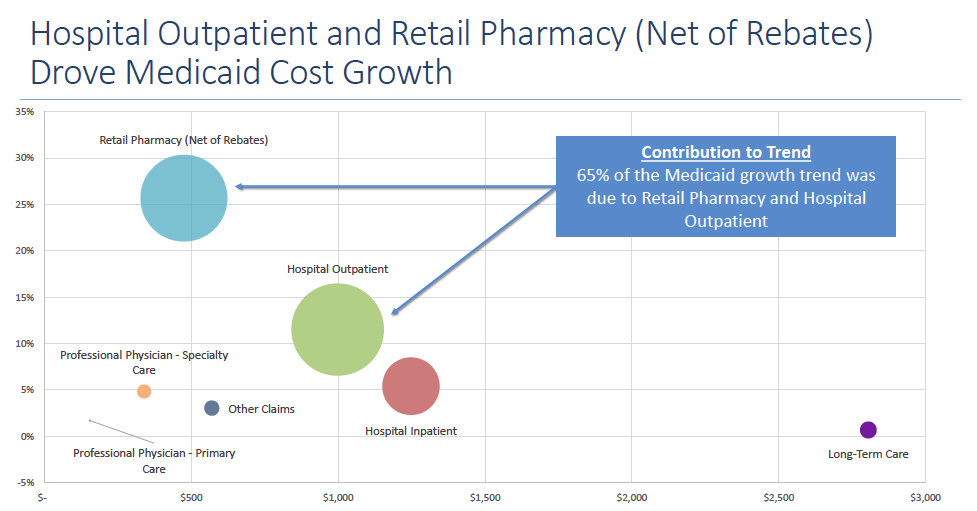

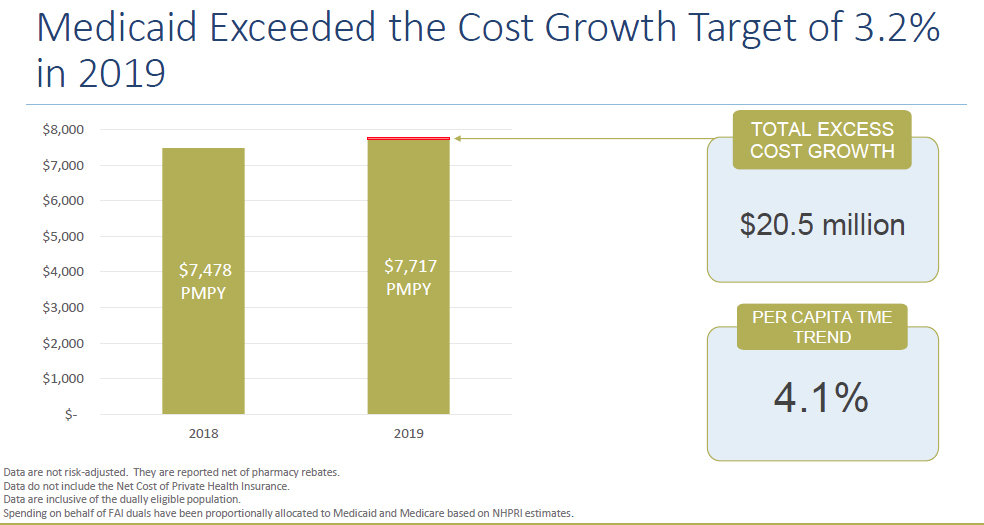

They released a report on April 29, showing that health care costs had increased by 4.1 percent between 2018 and 2019, exceeding the voluntary annual cap of 3.2 percent on health care spending, according to the R.I. Office of the Health Insurance Commissioner.

The data analysis was conducted by Michael Bailit, the president and principal of Bailit Health, using claims data from all the health insurance plans in Rhode Island, including Medicare, Medicaid, Neighborhood Health Plan, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Rhode Island, Tufts Health Plan, and UnitedHealthcare. [A separate analysis is now underway by Brown University’s School of Public Health, using the All Payer Claims Database.]

As ConvergenceRI reported: “Surprise, surprise, surprise.” [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “The high cost of living – and health care.”]

As one national health care expert told ConvergenceRI, in response to the latest data report: “The answers are obvious. Health care costs are going up because the prices keep rising. The biggest factor is the rise in the price of pharmaceuticals. It is not about utilization.”

What the numbers say – and don’t say

One of the biggest bugaboos around health care in Rhode Island revolves around the costs of Medicaid spending, including both federal and state funds, which has represented between one-quarter and one-third of the entire annual state budget in recent years.

The task of controlling spending in the state budget has often been translated into legislative efforts to contain rising Medicaid spending. The folly of legislative decisions to limit rates of reimbursement for nursing home and for mental health and behavioral health services was fully exposed by the coronavirus pandemic.

Roughly two-thirds of the state’s Medicaid budget is spent on long-term services and support – paying for the care of elderly and vulnerable residents in nursing homes and skilled nursing facilities. In terms of demographics, Rhode Island has one of the largest percentages of “old old” folks, people 85 years and older, who are often beset by the ravages of chronic diseases such as diabetes, dementia, Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s disease – all of which often require 24/7 caretaking.

Translated, the growth in Medicaid health costs is unlikely to decrease as long as the “old old” population keeps increasing. Before COVID-19, some 61 percent of the state’s Medicaid long-term care recipients lived in nursing facilities, according to R.I. EOHHS.

Indeed, the current scandal at the Eleanor Slater Hospital, which operates under the auspices of the R.I. Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities, and Hospitals [BHDDH], was precipitated in 2019 by the alleged inability to bill Medicaid for psychiatric services for long-term hospital patients. The shortfall forced the state to have to pay more than $100 million out of general revenue funds for services that might have been otherwise covered by Medicaid, according to reporting by WPRI.

Policy snafus

In the last decade, Rhode Island state government has attempted numerous strategies to reinvent the way that care is delivered to the Medicaid population in order to cut costs– often with not-so-great results.

• “Rhody Health Options,” [now referred to as the first phase of the Integrated Health Initiative], which was sole sourced to Neighborhood Health Plan of Rhode Island in 2013, with the goal of moving dually eligible residents of Medicare and Medicare back into the community, produced very limited results, far short of the 3,000 projected nursing home residents that would be returning to the community as a result of the initiative, despite an $80 million investment over five years.

• UHIP, launched in 2016, which had promised to create an online portal for determining Medicaid eligibility for patients receiving “long-term services and support,” proved to be another failed attempt at reinvention, leading to the R.I. Executive Office of Health and Human Services to make emergency interim payments of hundreds of millions of dollars to nursing homes to keep them financially afloat.

• Then there was the “Reinvention of Medicaid,” the signature program of former Gov. Gina Raimondo’s first term, which was enacted into law by the R.I. General Assembly in 2015.

Under the law, providers were mandated to create accountable entities to be overseen by Medicaid managed care organizations, with the goal of decreasing costs and improving health outcomes through a system of population health metrics.

Under the reinvention plan, those accountable entities that performed the best were to be rewarded with shared savings – but only after Medicaid, the state, and the managed care organizations [insurance companies] each took their cut, based upon quality reporting metrics.

The “reinvention” was financed in large part by more than $100 million in federal funds provided by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, with funding to last for approximately four years beginning in 2016. What happens when the federal monies run out is still a big, unresolved question, according to one physician. [The physician joked that the difference between accountable care organizations promoted under the federal Medicare program and accountable entities in Rhode Island was the lack of “organization” in Rhode Island, by definition.]

The players in the accountable entity sweepstakes were determined in part by the number of people served – those providers that served roughly 90,000 patient lives a year. The current R.I. EOHHS certified participants in the Medicaid accountable entity program are:

• Providence Community Health Centers

• Blackstone Valley Community Health Care

• Integrated Healthcare Partners, an amalgam of seven community health centers. [Thundermist Health Center, which had been a member of that group, has now chosen to withdraw and to go it along.]

• Integra Community Health Care [Care New England hospital network]

• Prospect Health Services Rhode Island [CharterCARE hospital network]

• Coastal Medical [now part of Lifespan hospital network]

What gets made public?

The analysis by the R.I. Health Care Cost Trends Steering Committee, conducted by Bailit Health, was, for the first time, promising to make public the data analysis results from the Medicaid accountable entities for 2019, comparing each of the providers’ performances by cost.

But, when the big reveal occurred at the end of April, only a composite score was given, in terms of cost performance.

The problem, it seems, was that the initial data compilation conducted by one of the managed care organization [insurance health plans] was not accurate.

ConvergenceRI asked Cory King, the chief of staff at the R.I. Office of the Health Insurance Commissioner, about potential problems with the data.

In response, King wrote: “First, the data that OHIC collects from the insurers is distinct from any data that the Medicaid program may be collecting or using for the AE [accountable entity] program.”

King recommended speaking with the R.I. Medicaid office about the AE data, because: “I am not close enough to that program to speak to it. Theoretically, the data should be well aligned. The AE contracts adjust the claims data [for example, truncation of high-cost outliers] that our data collection did not make. These adjustments are pretty much standard practice in the industry, and they serve to mitigate certain risks confronted by the provider due to costs outside of their control.”

As King explained it, the desire is to align methodologies: “We want to align methodologies going forward so that data published through the cost trends project is aligned with the standards of performance under the contracts.”

As it turned out, there were some problems identified with the data initially reported by one of the insurers. [Although King did not identify the insurer that had produced the questionable data, three different sources confirmed to ConvergenceRI that it was Neighborhood Health Plan of Rhode Island.]

King continued: “Second, we identified problems in the data reported to OHIC by one of the insurers. This really proved the value of doing data validation at the provider level, as the providers were able to call into question certain values in the reporting based on knowledge of their own data. To the credit of this insurer, they very quickly corrected these errors and resubmitted their data. We believe the data we have is accurate.”

That is an excellent positive reframe by King, but without specific data results for each of the providers to measure costs, the story remains somewhat incomplete, in ConvergenceRI’s opinion.

When asked by ConvergenceRI to at least provide the highest and lowest costs achieved in 2019 by Medicaid accountable entities, as well as the median, King answered: “For the AEs in our dataset, the annual medical trend [risk adjusted] from 2018 to 2019 ranged from 0.2 percent to 14 percent. The median was 3.05 percent.”

Translated, there is big gap between cost increases that range from 0.2 percent to 14 percent for 2019, a magnitude of difference of some 700 percent.

The other difficult question, not explored by the data results, is how any potential shared savings awards would be calculated. Should it be by the percent of decrease in costs year over year? Say, in a hypothetical example, the accountable entity with a 14 percent increase in costs in 2019, the highest level, had actually decreased their costs by more than 20 percent, compared with 2018 costs. Should they receive a greater percentage of shared savings?

In comparison, in another hypothetical example, should the accountable entity with the lowest cost increase in 2019, at 0.2 percent, be penalized when it comes to shared savings because their room for improvement in cost reductions, given their efficient operations, is much, much more limited?

Another question, which will remain unresolved until the data for all the performances by accountable entities is revealed, is this: Do the accountable entities associated with hospital systems have a higher cost of doing business because of testing and facilities fees?

Some final observations

Community health centers are the backbone providers of primary care in Rhode Island. During the last year, the providers and community health worker teams at community health centers have been at the front lines in attempting to halt the spread of the deadly virus, at the neighborhood level.

The delivery of health care services should not be made into a commodity similar to manufacturing widgets; rather, it is about building long-term relationships with patients, based upon trust.

Investing in place-based solutions in health equity, with a focus on prevention, not crisis management, should be the filter through which health care cost data is evaluated.