What is the best way to measure success in efforts to combat drug ODs?

As clinical interventions move toward more community-based approaches, the roots of the diseases of despair – loneliness, isolation, family and economic disruption – become more exposed

The current demographic trends promise to reinforce that gap, as more Rhode Islanders grow older and chronic diseases flower and peak, requiring more complex levels of care. The question is: will the R.I. General Assembly be willing to invest more money for such care, even if it means raising taxes?

PROVIDENCE – Since the R.I. Department of Health first changed its public health priorities in 2012 under Dr. Michael Fine, a primary goal has been to reduce the numbers of lives being lost to the opioid epidemic.

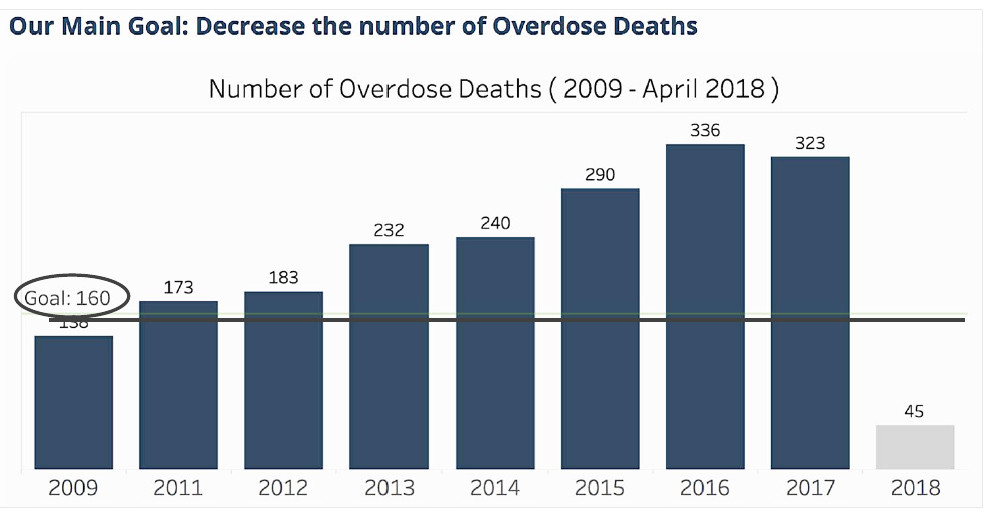

In 2015, the Governor’s Task Force on Overdose Prevention and Invention, created by Gov. Gina Raimondo, set the overarching goal of its work to save lives, with the admirable benchmark of reducing the number of overdose deaths by one-third in three years, based upon the 2014 death toll data, to roughly 160 deaths by 2018.

But the introduction of fentanyl into the market stream of illicit drugs dramatically changed the nature of the epidemic, increasing the number of deaths, as shown in the image atop this story, a slide showing the number of overdose deaths between 2009 and April 2018.

Despite the hard work and dedication of many, the number of overdose deaths hit 336 in 2016 and then fell slightly in 2017 to 323.

Measuring and then comparing the number of deaths per year is a kind of harsh, perverse benchmark: it does not show the potential number of lives that may have been saved, for instance, from increased naloxone distribution, from expanded medication-assisted treatment, from better access to peer recovery coaches at hospital emergency rooms, or from a more systemic approach through Centers of Excellence for clinical treatment of substance use and abuse.

Without those interventions, the death toll in Rhode Island could have become much, much worse, even if there are no measurements to capture their impact on the death toll.

Task Force interventions and efforts have included:

• Championing new community outreach efforts in West Warwick, Burrillville, Warwick and Providence, working in partnership with law enforcement to check in with those who have overdosed.

• Creating a working group to support the development of policies and protocols for substance-exposed newborns and their families. [The challenges facing a mother and her newborn in Rhode Island were recently documented in a New York Times story by Jennifer Egan, “Children of the Opioid Epidemic.” See link below to the story.]

• Developing and implementing a certification program for recovery housing, and helping to place some 169 people in certified safe residences. [There are 250 currently on the waiting list.]

• Supporting the efforts by the R.I. Department of Corrections to introduce all three FDA-approved medications to treat inmates who have opioid use disorders, which initial studies for the first six months showed a remarkable reduction of more than 60 percent in OD deaths for inmates leaving jail compared with the previous six months before the program was implemented.

• Helping to coordinate the launch of the Providence Safe Stations program, enlisting 12 fire stations to serve as an entry point where people in search of help and treatment could come on a 24/7 basis.

Only the efforts to create a comprehensive, statewide harm reduction strategy, included as part of Gov. Raimondo’s July 12, 2017, executive order, appear to be lagging. The first organizational meeting of the Harm Reduction Work Group was held last week on May 8, coordinated by Ryan Erickson of the Governor’s office.

More than opioids?

Despite all these positive, forward-looking initiatives, the death toll from opioid ODs remains a stubborn, persistent public health challenge. In many ways, the success of the current efforts by the Task Force has peeled back the onion layers, exposing the roots of more complex economic, social and health disparities.

For instance, a recent report by Blue Cross Blue Shield Association found that major depression is “the second most impactful condition on overall health for insured Americans,” outranked only by high blood pressure. In Rhode Island, the report identified that women and millennials have felt the impact most seriously, with diagnosis rates at 8.5 percent and 6.3 percent, respectively. Why is that?

The findings by the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association study underscored the research by sociologist Shannon Monnat at Syracuse University on the diseases of despair.

“I caution against over-focus on opioids,” Monnat said recently in a tweet from a conference. “Opioids are simply the drug of [the] day. As we know in upstate New York, in many of our rural communities, meth is more prevalent. We must tackle root causes, which also drive suicide, alcohol-related deaths and more.”

Monnat urged that there was a need to look at family, work and community factors to better understand drug mortality rates.

What is working well?

As part of the monthly meeting on May 9 of the Governor’s Task Force on Overdose Prevention and Intervention, following a review of the results achieved in the ongoing efforts focused on four-legged strategy of prevention, rescue, treatment and recovery, Senior Advisor to the Governor Tom Coderre led a facilitated discussion of task force members, asking: What’s working well? What might we do differently? And, what should be considered as we plan for the future?

Once again, what stood out before the open discussion was the hard work behind the achievements benchmarked by the data that was presented:

• As part of the rescue strategy, the goal to distribute 5,000 naloxone kits a year was met and exceeded in 2016, with some 6,341 kits distributed. The goal was increased to 10,000 kits of naloxone distributed; in 2017, there were 7,798 distributed.

• As part of the treatment strategy, the number of trained and waivered practitioners actively prescribing buprenophine had doubled since 2014, reaching a total 391 in 2018, compared to 192 in 2014.

• As part of the recovery strategy, some 309 peer recovery coaches had been trained by the first quarter of 2018, and all acute care emergency departments now have access to peer recovery specialists. [The idea to develop peer recovery coaches had been an innovative idea initially developed by the late Jim Gillen and Holly Cekala in 2012.]

Jonathan Goyer, a member of the Task Force and manager of Anchor Recovery’s Mobile Outreach Recovery Efforts, responding to the question of what the Task Force might do differently, stepped up to the plate in his sometime uncomfortable role as a truth teller.

Saying that he had been with thousands of Rhode Islanders involved with recovery, Goyer suggested a change in the investment priorities, pointing out while there was no waiting list for medication assisted treatment programs, there were more than 200 people on the waiting list for recovery housing. “That’s where we need to spending our money,” he said.

Dr. Nicole Alexander-Scott, the director of the R.I. Department of Health and co-chair of the Task Force, also pointed out the lack of people of color around the table at the Task Force meeting, save for her and two others, something that the Task Force needed to address.

And, Sen. Josh Miller, while praising the work of the Task Force in supporting legislative efforts in the R.I. General Assembly, also said, “Sometimes, it is like pulling teeth to create a list of priorities.”