What you do not know may kill you, when it comes to painkillers

Did you know? Coventry facility owned by Purdue Pharma legally manufactures as much as 750 tons a year of the raw ingredient oxycodone used in its prescription painkillers, according to a local doctor

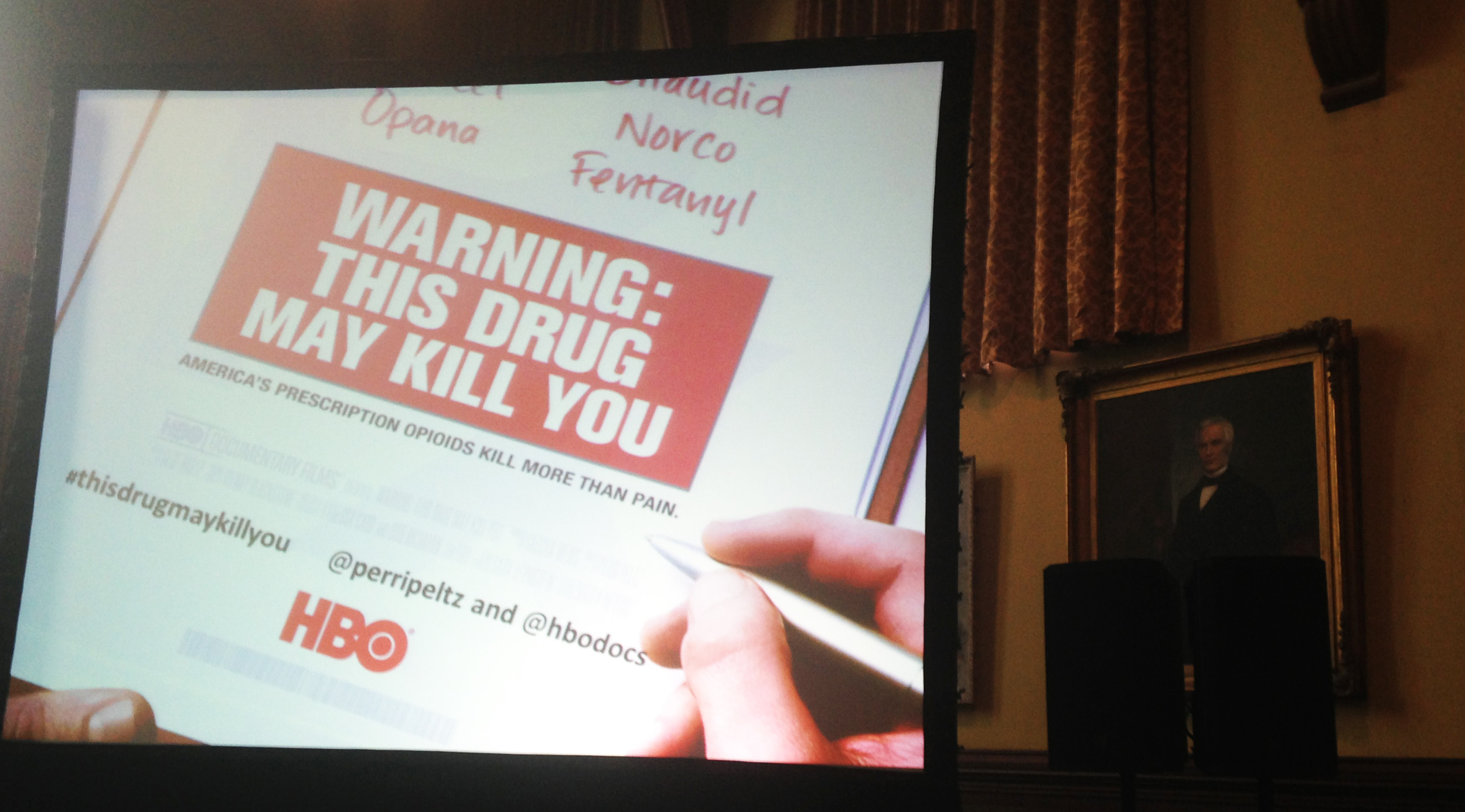

PROVIDENCE – A poignant new HBO documentary, “Warning: This Drug May Kill You,” had its world premier at Brown University on April 12, produced by Brown graduate Perri Peltz.

The hour-long film, told in vignettes of four families coping with addiction, drug overdoses and death, begins with a series of advertisements made by Purdue Pharma in 1999, touting its prescription painkillers, including one that proclaimed that “less than 1 percent” of patients taking the opioids ever become addicted.

It is the kind of “misleading” claim that ranks up there with what tobacco companies used to say about smoking cigarettes being safe, non-addictive and not harmful.

[“Purdue Pharma paid a $600 million fine, and three of its executives pleaded guilty to charges that they misled regulators, doctors and patients about the risks of the painkiller that is widely blamed for setting off the nation’s opioid crisis: OxyContin. All of those cases were initiated by the Food and Drug Administration,” as The Washington Post recently reported.]

Under the skillful production of Peltz, the film captures a human portrait of addiction and its sorrowful family consequences, connecting the role that prescription painkillers played in each of the tragedies.

“This film has no experts in it,” Peltz said, introducing the documentary, saying its purpose was the show everyone the humanity of people who suffer and deal with addiction.

This is not a story, Peltz continued, about a “problem of damaged people using good drugs. Nothing could be further from the truth. This is a story about good people who are falling victim [to addictive drugs].

The film begins with the story of Stephany, who, in her own words, described how she began taking painkillers as a teenager to deal with the chronic pain from kidney stones, prescribed by her physicians. It soon led to sharing the pills with her older sister, then to snorting heroin, then to injecting heroin, to recovery, to relapse, to recovery, to relapse again, and most recently to recovery.

“I feel like I had a relationship with heroin,” Stephany said, looking into the camera. “I loved it, and it loved me.”

Later on in the documentary, Stephany’s mother is shown going over instructions on how to use Narcan with Stephany’s daughter, 6, in case she finds Stephany unresponsive.

Then Stephany’s mother is shown taking Stephany to a police station, to enter into a drug recovery program, with Stephany in withdrawal, throwing up while trying to walk into the station.

What we do not talk about

None of this was “breaking news”: Rhode Island, like many other states, has been ravaged as a result of the epidemic of drug overdoses related to prescription painkillers and illicit drugs, such as heroin and fentanyl. The current toll for overdose deaths in 2016 is 336 and counting, a 16 percent increase from 2015.

The connections between the decision by the Joint Commission to approve the clinical practice of using pain as a fifth vital sign, the promotion of prescription painkillers, and the epidemic of drug overdoses is a well-trod story line.

The debut of the documentary was not the kind of breaking news story generated by federal authorities, who held a news conference the very next day, on April 13, touting the “breakup” of what was termed a significant international drug ring operating in Rhode Island, in what the feds called “Operation Triple Play,” as part of the FBI Safe Streets Taskforce.

However, what was startling news was the information delivered by Dr. Russell J. Ricci to the audience, during a question-and-answer session following the documentary, that Purdue Pharma owned a manufacturing plant at 498 Washington St. in Coventry, known as Rhode Technologies.

The plant manufactured some 750 tons a year of the raw ingredient used in the manufacture of its prescription painkiller pills, in huge vats, according to Ricci. The ingredient is then apparently shipped to facilities in either North Carolina or New Jersey where it is made into pills.

Translated, Rhode Island is the home of one to the manufacturing plants owned by Purdue Pharma, a veritable ground zero for the prescription painkiller plague.

Despite the interjection by Ricci with that news, the conversation at the April 12 event following the premier of “Warning: This Drug May Kill You,” continued on its own trajectory.

Marketing pain pills

Reporter Eric Eyre of The Charlestown Gazette-Mail in West Virginia won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for his story, “780M pills, 1,728 deaths,” recounting how drug wholesalers made billions shipping pain pills into West Virginia.

In his award-winning exposé, Eyre wrote: In the drug distribution industry, they’re called the “Big Three” — McKesson, Cardinal Health, AmerisourceBergen — and they bear no resemblance to the mom-and-pop pharmacies that ordered massive quantities of the drugs the wholesalers delivered in West Virginia.

Between 2007 and 2012 – when McKesson, Cardinal Health and AmerisourceBergen collectively shipped 423 million pain pills to West Virginia, according to DEA data analyzed by the Gazette-Mail – the companies earned a combined $17 billion in net income.

Over the past four years, the CEOs of McKesson, Cardinal Health and AmerisourceBergen collectively received salaries and other compensation of more than $450 million.

In 2015, McKesson’s CEO collected compensation worth $89 million — more money than what 2,000 West Virginia families combined earned on average.

“What’s most remarkable is that the boards of the companies are paying the CEOs as if they were innovators and irreplaceable entrepreneurs, when in fact they are just highly paid middlemen, betting on market consolidation and ever-rising drug prices,” said Ken Hall, international secretary-treasurer of the Teamsters union.

Translated, there continues to be a strong profit incentive for companies to market millions of addictive prescription painkillers, despite the rising death toll.

Holding painkiller manufacturers accountable

Washington Post reporters Lenny Bernstein and Scott Higham, in a story published on April 2, detailed the federal government’s struggle to hold opioid manufacturer’s accountable.

According to the reporters, some 66 percent – some 500 million pills of all oxycodone sold in Florida between 2008 and 2012 came from Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, “one of the nation’s largest manufacturers of the highly addictive generic painkiller oxycodone.”

A prosecution of the company could have resulted in fines up to $1.3 billion; prosecutors proposed settling the case for $70 million; a tentative agreement has apparently been reached in the case to settle for $35 million fine, what one government official called “chump change” for Mallinckrodt, according to the story.

As reporters Bernstein and Higham wrote in their story: Prosecutors said that they could fine the company as much as $2.3 billion because 222,107 orders to Florida were “excessive” and should have been reported as suspicious.

Or they could fine the company up to $1.3 billion based on an analysis of the 217,022,834 Mallinckrodt 30 mg. oxycodone tablets that were sold for cash in Florida in 2009 and 2010.

“As you are aware, significant cash sales are an indication of diversion,” prosecutors wrote in their offer.

But the big buildup resulted in a much smaller proposed fine. Despite the billion-dollar figures bandied about, the prosecutors proposed settling the case for $70 million. They cited the “litigation risk” they faced if the case went to trial, Mallinckrodt’s previous legal arguments and the size of other recent settlements with drug distributors.

This year, on Feb. 7, Mallinckrodt told its shareholders in an SEC filing that the investigation “will not have a material adverse effect on its financial condition” because it has set aside the money.

Sources close to the negotiations said that the two sides had recently reached a tentative agreement to settle the case for $35 million. With final approval pending from the Justice Department, some of those who worked on the case said they are deeply disappointed by the dollar amount of the proposed fine.

The reporters compared the size of the proposed $35 million fine with what other drug manufacturers had paid:

Drug manufacturers have paid much larger fines for other misdeeds. Glaxo-SmithKline was fined $3 billion, and Pfizer was fined $2.3 billion for illegally promoting off-label drug use and paying kickbacks to doctors.

The largest fine the DEA has levied against a drug distributor was the $150 million that McKesson, the nation’s largest drug wholesaler, recently agreed to pay following allegations that it failed to report suspicious orders of painkillers.

For a company the size of Mallinckrodt, a $35 million fine is “chump change,” one government official said.

Translated, the federal government has not been willing to use the full force of its criminal justice system to punish the for-profit drug companies and their executives for manufacturing and marketing addictive prescription painkillers.

What we don’t talk about when we talk about drugs

During the screening, a woman sitting behind ConvergenceRI was often crying, the tears literally rolling down her face.

Afterward, ConvergenceRI talked with her. Patricia voiced her frustration with the conversation that followed the documentary, particularly the focus on clinical, medication-assisted interventions such as suboxone and methadone.

Patricia’s daughter is currently in recovery; Patricia’s husband died 10 years ago from a drug overdose from prescription painkillers.

“I don’t think that more pills or more drugs is the answer,” she said. “It’s sort of stop gap, a grasping at something. But I don’t think it’s the answer.”

My daughter, Patricia said, “has used all of those – methadone, suboxone, and it has not helped. There has to be something more.”

Her daughter, Patricia continued, is most recently in a holistic treatment. “She’s doing better than she ever has.”

What didn’t work for her was the 30-day stint in treatment and then, according to Patricia, being thrown back out on the street. “The 30 days are spent hashing over old things, sharing with people all those things, but there is really no therapy,” Patricia said. “The people there aren’t getting better.”

As an afterthought, Patricia asked an extremely cogent question: What do you know about the suboxone treatment center being advertised a few blocks from the Brown campus?

Translated, the efforts to promote clinical approaches to medication-assisted treatment in Rhode Island may have its own profit-making downside.

What the experts had to say

The showing of “Warning: This Drug May Kill You,” was followed by a brief panel discussion, moderated by Fox Wetle, outdoing dean of the School of Public Health, which included Dr. Nicole Alexander-Scott, director of the R.I. Department of Health, Dr. Josiah Rich, professor of Medicine and Epidemiology at the Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown, Rebecca Boss, director of the R.I. Department of Behavioral Health, Developmental Disabilities, and Hospitals, and Peltz.

Alexander-Scott and Boss are the co-chairs of the R.I. Overdose Prevention and Intervention Task Force, and Rich is a member. Many members of the task force were present in the audience.

For Rich, one of the most memorable parts of the film was the fact that when a women succumbed to an overdose from prescription painkillers, hardly any of her friends showed up at her funeral, addressing the stigma of addiction.

Rich also addressed what he called the lack of understanding of addiction as a chronic disease where the receptors in the brain get rewired, and that relapses are a predictable part of the disease.

He lauded the fact that people are so desperate that they want to get into treatment. “But 90 percent of people who go into treatment, into detox, they relapse when they come out,” he said. Relapses, he continued, are part of this disease.

Rich talked about what he called the primitive, “reptilian” part of the human brain, different from the cerebral cortex and the ability to reason, think and talk. “The reptilian brain is hard-wired for survival, and it makes you do thing s that you wouldn’t otherwise normally do.”

With addiction, he continued, even after detox, “Those neural pathways are still changed in the brain.”

In turn, Rich promoted medication assisted treatment, a key component of the task force’s action plan, as being highly effective – “They are the best tools we have right now.”

Rich also discussed the dangers of fentanyl, which has become a major concern in the stream of illicit drugs because it is so dangerous in small quantities. “An amount equal to a half a grain of rice of fentanyl can kill you. A single dose of Narcan may not be enough [to revive someone.]”

While the experts did talk some about the responsibility of doctors to not prescribe opioid painkillers, at the risk of “doctor-bashing,” others talked about the dangers of removing patients too quickly from opioids once they had become addicted.

No one, however, addressed the corporate responsibility of drug manufacturers and drug marketers behind the prescription painkiller epidemic. Nor did anyone return to the news raised by Ricci about the Purdue Pharma manufacturing facility here in Rhode Island.