When radical change, connectedness and hope converge

In the post-pandemic world, there is much that can be learned from community-based recovery efforts about what “recovery” actual means

We need to pay attention to the language being used: Information being “weaponized” is a military construct, them vs. us, not so different from the way that President Trump talks about the coronavirus as “the invisible enemy.”

A funny thing happened with R.I. House Speaker Nicholas Mattiello as part of one of his regularly scheduled appearance on WPRO. [Allowing the Speaker to have unfettered access to the airwaves, whether talking to Gene Valicenti or Tara Granahan, is another question altogether.] Mattiello admitted that he did not know what Juneteenth was, and then questioned whether or not slavery had ever existed in Rhode Island.

Imagine that. For all the history and information and documentation around Rhode Island’s intimate connection to the slave trade – in Newport, in Bristol and in Providence, somehow that ‘information” had not entered the consciousness of Mattiello. In one dramatic verbal blunder, the arguments around eliminating “plantations” from the name of Rhode Island had become a winning argument, thanks to the House Speaker.

Last summer, spurred on by the death of Toni Morrison, and her efforts to build “benches by the side of the road” as a place to remember slavery and to honor the descendants, ConvergenceRI sought to build momentum around creating such a memorial bench in Providence. That effort had to be put on hold, for personal reasons, following complex spine surgery in September of 2019.

It now seems an appropriate time to rekindle that effort. If nothing else, such a bench alongside the pedestrian bridge would provide an opportunity for all citizens of Rhode Island, including the House Speaker, to embrace the legacy of slavery as an intrinsic part of the state’s history, and to move forward in a positive way around change, in which personal and community recovery requires a radical reconstruction of ourselves and our history.

PROVIDENCE – When we in addiction recovery tell our story, we often cite an inflection point – what William White refers to as the catalytic event or process propelling one from addiction to recovery.

For some it is a spontaneous event that leads to transformation [what is known in the clinical literature as quantum change or transformational change, a recovery initiation that often involves a profound religious, spiritual, or secular experience that radically redefines one’s personal identity and interpersonal relationships, and suddenly and completely alters one’s prior pattern of alcohol and other drug use].

For others, it is the process of an accumulation of life negativity and pain that is simply expressed as: “I got sick and tired of being sick and tired,” and that leads to transformation.

Today, in our society, we may have reached a couple of inflection points. We have the opportunity for transformative recovery from our shameful history of racism. We have the opportunity for transformative recovery from the weaknesses and inequities in our health care system.

As ConvergenceRI recently noted: “At some point, discussions focused on “recovery” should remember to include groups such as RICARES, Rhode Island Communities for Addiction Recovery Efforts, sharing their expertise about what “recovery” means in the context of community, resilience and connectedness.”

There has been an explosion of recovery research and science in the last decade. Large-scale primarily qualitative studies have aggregated and analyzed the lived experience of those in successful long-term recovery. Those studies have reinforced the basic principles and practices that we have learned over the centuries of participation in community-based recovery support groups.

We believe that many recovery principles and practices are transferable to our present situation. These include radical change, connectedness and service, and hope.

• Change. Our personal recovery requires a radical reconstruction of the self. We have to start by totally altering our relationship with alcohol and other drugs. This is necessary but not sufficient. We also have to make an internal system change – to our attitudes, our beliefs and our behaviors. A return to “how it was” is futile if “how it was” contained the seeds to the problem.

Recovery connotes a return to health following trauma or illness. America’s historical pathology of racism has once again smacked us in the face of our national consciousness. Too many of our citizens continue to live with the effects of the intergenerational trauma caused by dehumanizing racism since the first slaves arrived almost 400 years ago, by the decades of Jim Crow-ism, of de facto segregation, and of countless occurrences of violence and neglect.

Racism is embedded into our institutional structures. A sign at a North Kingstown protest two weeks ago expressed it as: “Racism is so American that when you protest against it they think you’re protesting against America.”

Dr. King wrote: “The Black revolution is much more than a struggle for the rights of Negroes. It is forcing America to face all its interrelated flaws – racism, poverty, militarism, and materialism. It is exposing the evils that are rooted deeply in the whole structure of our society. It reveals systemic rather than superficial flaws and suggests that radical reconstruction of society itself is the real issue to be faced.”

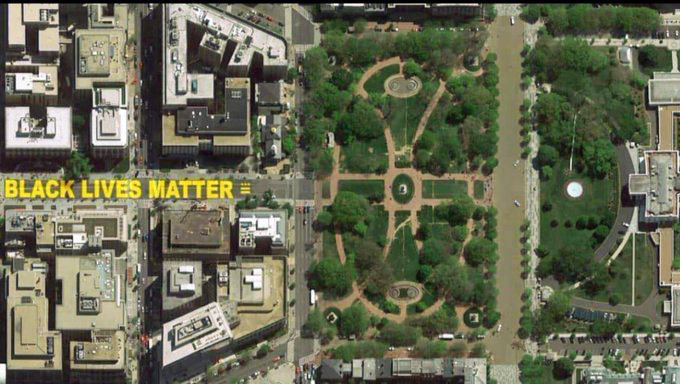

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor recently wrote in The New Yorker that outlooks have been shaped during the past several years by the anti-racist politics of the Black Lives Matter movement, which move beyond seeing racism as interpersonal or attitudinal, to understanding that it is deeply rooted in the country’s institutions and organizations.

In addition, it is self-evident that our national health care system is ill. We spend, by far, the most in the world on health care. However, the U.S. ranks 46th in the world in life expectancy and 33rd in the world in infant mortality rate, according to a JAMA report published in 2018. The delayed response to COVID-19 is a further reflection of that illness. The U.S. accounts for 5 percent of the world’s number of annual deaths [all causes], but we presently have 29 percent of the world’s total COVID-19 deaths.

The COVID-19 pandemic has once again exposed the extreme health disparities between Black and white [and between the wealthy, the poor, and working-class people].

National Public Radio recently reported that evidence has emerged that doctors are less likely to refer African Americans for testing for COVID-19 when they exhibit symptoms. These familiar patterns of racial [and economic] bias do not simply reflect individual bias, or nefarious intent. Rather, they are a symptom of the broken system, over a century in the making, in which American hospitals operate and medical personnel are trained and educated.

Yes, over a century of awareness. In 1913, “The Crisis,” the publication arm of the National Association for Advancement of Colored People, first raised the issue of racialized medical malfeasance with its investigation into Harlem Hospital.

And this month, the Black Moms Matter protest by staff at Women’s & Infants Hospital focused attention on the need to address and correct the prevalent maternal health disparities for black mothers in Rhode Island.

• Hope. Poet Emily Dickinson wrote: “Hope is the thing with feathers that perches in the soul, and sings the song without the words, and never stops at all…”

Hope is the critical ingredient of recovery. The pain and consequences of our addictive behavior were not enough to get us into recovery. Indeed, the defining characteristic of addiction is continued use despite the profound negative consequences.

A definition of despair is the complete loss or absence of hope. As humans, we can understand how despair quickly creeps into our lives when we are faced with circumstances beyond our control or a terrible loss of any kind.

The despair is continually reinforced by, for example, the racially differential institutional responses to recent drug epidemics. The response to the suffering of Black people during the crack cocaine epidemic resulted in criminalization that devastated Black communities. The response to the suffering of rural whites during the opioid epidemic was an empathetic social response to those trapped in circumstances not of their making.

In recovery, we search for and we foster hope, for ourselves and for others. We see hope reflected in the resilience of the Black communities that continue to fight, struggle and refuse to surrender, in the continued insistence on equality, equity, and an end to the systemic violence against them.

We see hope as nationally expressed by the active presence and leadership of both young people and the heterogeneity of people in demonstrations and protests. As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor wrote: “The protests have involved not just students or activists; the demands for an end to this racist violence have mobilized a broad range of ordinary people who are fed up. And, young white people are compelled to protest not only because of their anxieties about the instability of this country and their compromised futures in it but also because of a revulsion against white supremacy and the rot of racism.”

•Connectedness and service. We historically view recovery as more about “We” and less about “I.”

“We” connotes inclusion and connectedness. Isolation was a symptom of our addiction for many of us. Addiction recovery is very difficult to attain in isolation. A task of early recovery is to develop and enhance the human connections that are the source of hope and inspiration. Our connections help us heal our wounds.

We know that our sustained and meaningful recovery occurs in the community. Recovery is not a top-down process, not something that is done to us [i.e., as the result of professional intervention]. Recovery is a process that we develop and through which we learn how to self-manage. The support of our community works as an agent of healing to build the connecting tissue that supports recovery.

Our societal recovery cannot be dependent on a top-down systemic intervention. The systemic interventions to racism have historically been incremental and generally only occurred with extreme community-driven pressure [e.g., the Abolitionist movement of the 1800s, the Civil Rights movement of the 1900s].

There has not been even incremental positive change in our health care system [characterized by Dr. Michael Fine as actually a health care market system] since the establishment of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in 1965. Medicaid is continually under attack. Meaningful reform suggestions are branded as “socialism.”

We have learned that “service” is a powerful means to develop connectedness and community. We express service in our lexicon with phrases such as “pay it forward” and “you can’t keep it if you don’t give it away.”

Service is a means to connect emotionally with other human beings. It provides a way for us to escape our own pain and to experience connectedness. Service is the antidote for the cultural suppression of empathy and caring.

In our post-pandemic world, moving forward, our societal recovery must be inclusionary and intentional. We must mindfully foster and enhance the connectedness of us all. William White noted that it is the act of listening – achieving self-silence – that is the precursor to empathic identification and connectedness to others. It is the medium through which the addicted person breaks out of isolation. It is the beginning of self-inventory and self-renewal.

Some final points

We acknowledge that the vested interests continue to be invested in, and depend on, the racial structure to our system. We acknowledge the vested interests that prevent our irrational and inadequate health care system from reform.

We know that recovery is difficult, confusing, and often painful work. But we have experienced the truth of Frederick Douglass’s statement that without struggle, there is no progress.

We know that recovery is redemptive and that recovery is transformative. It is clear today that the United States needs redemption. And we must believe that societal transformation is possible.

We know that recovery is the expectation, not the exception.

Ian Knowles is the program director at RICARES and a frequent contributor to ConvergenceRI.