Hey farmer, farmer, put away your DDT

Telling the tale of the fundamental fracture in the way that “science” regulated DDT, marketing the poison as a beneficial consumer product

Under state law, when state and federal funds are being spent on rehabilitation, the owners must be responsible for conducting what is known as an “asbestos abatement plan” that is approved by the R.I. Department of Health, in order to “remove, encapsulate, enclose, repair, or otherwise disturb or abate asbestos at a facility,” according to Joseph Wendelken, the agency’s public information officer.

Translated, the firm that owns the building, High Rock, is required to conduct an asbestos survey of the building, using an agency-licensed asbestos consultant.

How much will that cost? A very good question. Has such an asbestos survey been calculated as part of t he costs of rehabilitating the building? An even better question.

The disliked reality is that the entire building is probably riddled with asbestos, given the age of the building. Any reconstruction of the building will require a major investment in asbestos removal. A small abatement project involving asbestos was conducted in 2012 by Bank of America, according to the R.I. Department of Health.

In terms of what that might mean for the rest of downtown Providence, an asbestos abatement project of that large a scale might require for the entire structure to be wrapped in plastic, as if it were a Christo art project.

In honor of Earth Day, perhaps a member of the Rhode Island news media will follow up and ask the owners of the building regarding the likelihood of asbestos abatement needed. ConvergenceRI did follow up with a spokesman for CommerceRI, Brian Hodge, but has not received a response.

Editor’s Note: A new book, How To Sell a Poison: The rise, fall and toxic return of DDT, by Elena Conis, was published last week, a poignant marker for the 52nd celebration of Earth Day. The cover of the book is illustrated by an iconic photo of a woman in a bathing suit, drinking a Coke and eating a hamburger at Jones Beach in New York, surrounded by a fog of a sprayed mist of DDT, in a story that the manufacturer of the fogging device “placed” in LIFE magazine in 1948, promoting the safe use of DDT spraying to prevent the spread of polio by killing flies.

The spraying of DDT did not halt the outbreak of polio in communities across the nation, but the photograph did capture the way that the spraying of DDT was marketed to the American consumers as a safe practice.

In PART One, ConvergenceRI shared an extended Twitter thread by the author, Elena Conis, about how the image ended up on the cover of her book. In PART Two, ConvergenceRI shares a transcription of an interview with the author, which took place on Wednesday evening, April 12, the day that her book was officially released.

The interview was conducted by Sally James, in a program produced by Town Hall Seattle. A similar kind of interview will be conducted on Monday evening, April 18, with Kerri Arsenault, author of Mill Town, interviewing Elena Conis, in an event sponsored by the Harvard Book Store.

The transcription by ConvergenceRI begins a few minutes into the interview, after Sally James asked a question about the choice of the cover photograph of the model, surrounded by a fog of DDT, while drinking a Coke and eating a hamburger, on Jones Beach on Long Island.

PART Two

PROVIDENCE – If the interview with author Elena Conis, historian, had been done as a podcast, the not-so-subtle theme music playing in the background might no doubt have been Joni Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi,” with its admonition to farmers “to put away your DDT” and leave the birds and the bees.

The interview by Sally James had begun with a question about the choice of a provocative photo of a model in a swimsuit on Jones Beach.

CONIS: …[The company] made machines that created smokescreens, machines that created smoke to cover movements of Allied troops [during World War II].

And, after the war, this company, TIFA, they were looking for a new market for their smokescreens.

And so, we are getting to the model, it seems really far from the model, but we are getting to the model.

This company said, “What if we take a couple of things, put them together, and put DDT in our smokescreen machine, and use it to spray American cities.” They figured it was kind of a long shot, and they ended up finding some really interesting ways of convincing U.S. cities to spray themselves with DDT, using their smokescreen machines.

But, one of the things they did was run – we would call them ads, but at the time, they looked like articles. We might call them today “sponsored content.” It was articles that TIFA wrote and then supplied their own images for, and that then ran in magazines, like LIFE and Time and elsewhere.

So, in this 1948 issue of LIFE magazine, there was an article, [written and] produced by TIFA, for readers to understand why it could be helpful for them to spray their communities with DDT, using one of their smokescreen [machines].

This cover image [for my book] was one of five images attached to this article; it is the raciest one; it is also the last one [used]. Most of them were actually pretty mundane. [The other images] showed the smokescreen rolling across the beach, or [the smokescreen generator] parked outside a suburban home, fogging the entire lawn and all the trees and shrubs with this DDT mist.

And, the very last image is this image of this woman, and it says in the caption, model Kay Heffernan, sprayed with DDT, I think it was on Jones Beach.

When I saw this image, at first, I wasn’t that interested in it, because it seemed like kind of an odd thing. Why include this picture of this woman in a bathing suit?

And, if you look at her closely, which, if you get a copy of the book is easy to do, there are things about her. She’s got perfectly coiffed hair, with a lot of jewelry, lots of bling on her fingers. And, yes, she is eating this hamburger, she is sipping a Coke, and she is in [wrapped up in] this cloud of DDT.

My read of it was: this was TIFA’s last-ditch effort at the end of this article, [saying]: OK, if you are not convinced that [the spraying of DDT] it is going to make the beach more pleasant, or your suburban neighborhood more pleasant, maybe you are convinced that is going to attract your attention because of this racy model who is surrounded by this mist.

I have to admit, when I first saw the [suggested] cover, I was really skeptical about the decision to use it, on the cover of my book, a book in which I was telling the story of this quote unquote “wonder” chemical, DDT, why we began to use it, why we rejected it, and who was [now] behind the move to bring it back.

And this image, initially, seemed like a distraction to me. Part of what bothered me about it was what it was meant to do, using the female form, using sex and celebrity, the idea that she was a model, to sell us on something.

As I looked at the image more and more, I went and I dug up the original image in its original context, and also the original images that the photographer had taken, which were even racier, if you can imagine.

Because the bathing suit that she is wearing actually has breast darts, and so, her physique is even more pronounced in the original.

And, as I looked at it, I started to feel haunted by it, because one of the things that I knew in tracing the history of DDT was that decades later, scientists studying the chemical would realize that women who were exposed to high amounts of DDT when they were young girls, in late childhood, in early teenage years, they faced an increased risk of breast cancer later in life.

And, not only that, there were intergenerational risks, too, that their children – and then their grandchildren, granddaughters in particular, faced increased risks, not only of breast cancer, but risk factors associated with the disease. And so, suddenly, this image meant a lot more to me. That is a kind of long answer to your question….

JAMES: DDT is an endocrine disruptor, correct?

CONIS: Yes, it is.

JAMES: Some people in our audience may be familiar with that term, even though they may associate that phrase with other chemicals that have been in headlines. [Your] book has three acts – the promotion and boosterism [of DDT], then the regulations, the beginning of people questioning [its safety]…

For me, Chapter Nine [in your book] is a crucial chapter, when hearings begin on pesticides in general. I wanted to bring attention to a phrase you used. You called it a “fundamental fracture” in the way that the FDA, the CDC, and the USDA all had some hand in regulating chemicals.

[Editor’s Note: Conis wrote: “…The fundamental fracture in the regulation of poisons had been laid bare.” She continued: “The USDA was responsible for figuring out whether chemicals were getting into the food supply – and it did. The FDA, which had split off from the Department of Agriculture in 1940, was responsible for determining whether those chemicals posed a problem for human health. Because some of those same chemicals were used in public health efforts, the CDC also bore some responsibility. And with labs in all three institutions adhering to different scientific frameworks, the result was what historian Frederick Davis called a ‘cloud’ of scientific uncertainty and a bureaucratic stalemate.”]

You describe how [the agencies] used different lenses with which to [view DDT], , and then used, literally, different lab techniques, so the data really wasn’t exchanged easily between them. And, it hindered public understanding. Could you describe a little of that bureaucratic problem?

CONIS: Sure. I am happy to. We tested this chemical in the context of war. USDA scientists tested it extensively; FDA scientists tested it at the same time; this was in the 1940s, and they came to pretty different conclusions.

The USDA scientists were like: It kills bugs. Great. They sprayed it in larger environments. They were like: Oh, it seems to kill some other stuff. That is a little troubling. Let’s go back next week and see how the environment looks. OK, it looks OK – the fish came back, the birds came back.

The FDA scientists, meanwhile, were administering [DDT] in the lab, to lab animals, and they were administering really high doses. They wanted to see how high a dose would actually harm the animals. Among these scientists at the FDA were some who noticed early on that the chemical was actually accumulating in the milk, the breast milk of animals, and then being passed on to their pups, when using dogs in the experiment.

We had these different groups of scientists [going] in really different directions, studying it in different ways, and noticing different things about it, each of them with their own respective responsibility for understanding pesticide risks and safety, but with a different view [about] the process.

And, this fracture existed throughout the 1940s, throughout the 1950s, throughout the 1960s.

And, in the 1950s, our federal government held hearings on chemicals in food, which included pesticides, and some of the cracks in our regulatory infrastructure started to show. One of the solutions that we came up with the 1950s was an amendment to the food and drug law, which said: Let’s do this; if there is any chemical which is shown to cause something really serious in animals, let’s not allow it in the food supply. And the really serous thing was cancer.

We left the 1950s with at least this moderate change – well, at the time, it was a significant change, in how we were regulating chemicals. Then, in the early 1960s, Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, and this throws [the use of] chemicals, particularly [with] pesticides regulation, even more into question.

And, at this point, we have a whole host of interventions, both at the state level and the federal level. President Kennedy asked for an investigation. And, Congress is doing its own investigation. And everyone is thinking how is it we can prevent the kind of harm that Carson is describing in Silent Spring – which, for viewers who haven’t read the book, it focuses heavily on the harm [that DDT is doing] to wildlife and ecosystems. She also talks about the potential harm to people and their long-term health, in particular.

By the end of the 1960s, there are folks pressing for outright bans on these chemicals, including a ban on DDT.

I don’t want to get too far ahead [of the story], but some of these folks are pressing for this at the state level. Later on, they take the fight to the federal level. At the state level, in the late 1960s, they start to make some progress.

Your question was about the science, and by the late 1960s, we still haven’t solved that problem.

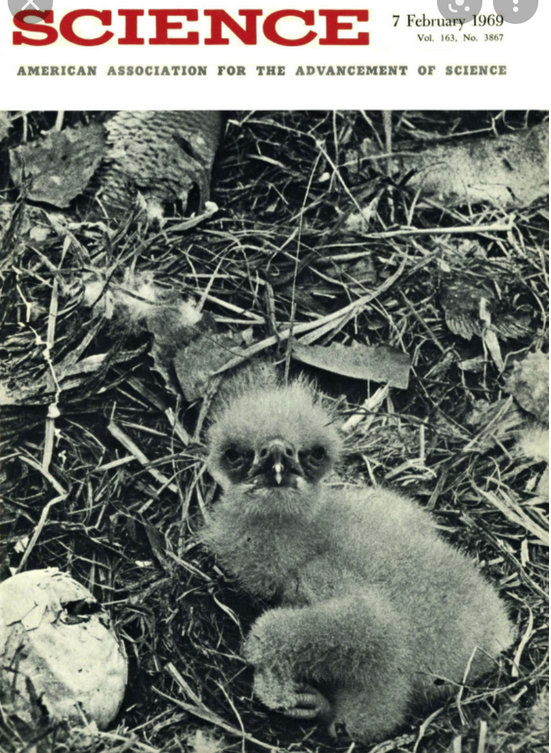

JAMES: This is a good time to bring up another image, and correct me if I am wrong: this is an image described from the chapter in your book called, “The Birds.” And, it has to do the origins of the Environmental Defense Fund, if I am correct. It is an image of a baby eaglet, and I am going to let Elena take over in telling the story, how, because of a dinner, this image ended up on the cover of Science magazine in 1969.

CONIS: It is an interesting story. And, it is directly related to the tensions and the struggles that were happening in the states in the 1960s, when local groups of citizens were coming together and asking: How can we curb or stop the use of these pesticides, particularly DDT, in our communities?

On Long Island, there were a group of scientists, some of them at Brookhaven National Labs, and at Stony Brook University, who had gotten together, and they wrote a letter to the local newspaper about their county’s use of DDT. That letter caught the interest of a local lawyer, and they decided to sue, locally, to stop the use of DDT.

[The lawyers], a couple of guys in their mid-30s, found that this approach was really effective. They found that by announcing that they were going to sue, the county got so cautious that it sort of backed down. It also got a bunch of press. The [lawyers] came up with a formula, thinking, well, if this is going to work here, maybe we can try it elsewhere.

Two of the people who were involved with the lawsuit on Long Island then went and helped community groups in Michigan and Wisconsin to file suit.

The group that was from Long Island started to call themselves the Environmental Defense Fund, and they started to help this group in Wisconsin. They learned that this group was so well connected, and they decided to try a few different approaches in Wisconsin, to see if one of them was more effective than the others in stopping the use of DDT.

What they ended up learning through all of their connections was that, at the time, Wisconsin had a state law that allowed citizens to petition the state government, and the petition could say, “We think that this is a pollutant; can you hold hearings to determine if it is?”

And so, they petitioned the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources; the Department held hearings. And, they did what they had done in Long Island – they publicized the hearings. And, they got a lot of attention. They got reporters, not just from local newspapers and magazines but from national outlets, [to cover the hearings.]

The folks who comprised this new group, the Environmental Defense Fund, made a point as the hearings were happening, of inviting folks out to dinner and saying, “We are going to take you out to dinner and tell you all about what we know about the science about how DDT and other chemicals are harming ecosystems.

And, at one moment in the hearings, they had invited an ornithologist from the University of Wisconsin at Madison to present some of his research. This ornithologist, Joe Hickey, had studied what had happened to the bird populations in a few places in Wisconsin, before and after DDT spraying.

And, he was one of a number of scientists who noticed two things were happening. One, the chemical DDT was toxic to some birds immediately, and it could cause, particularly at the right doses, immediate die-offs of bird populations. But Hickey also noticed that the spraying could have a slightly less acute effect, where the birds that [were exposed] in doses that were not lethal were still affected by the chemical, and were laying thinner eggs as a result.

And, Hickey, in his testimony in Wisconsin, ended up showing that photo of the eaglet. He described how this was an eaglet that had just hatched in a nest where the egg just adjacent was too thin, and for Hickey, it was an illustration of the long-term effects that egg shell thinning could have on bird populations.

Over dinner, at one of these nights out with reporters and the folks from EDF, Charles Wurster and Victor Yannacone, they offered to give the reporters this photo, and give them the use of it. One of the reporters who was covering the hearings for the journal, Science, ended up taking them up on the offer, getting it on the cover of Science, and in no time, this was even before the hearings were [completed], subscribers were seeing this really heart-wrenching image of this eaglet, almost gesturing to this broken shell in the nest, and it was an extraordinary effective.

JAMES: Is it fair to say that it was the equivalent in 1969 of going “viral?”

CONIS: I think that it is probably fair to say. This was one of those images that was so hard to ignore, for sure.

JAMES: One of the things that the book includes, which is so delicious but also complicated, is that you include a lot of the behind-the-scene stories, a lot of how the sausage is made, and the sausage of regulation is complicated.

I wonder, if you want to explain to us, I am not sure I should call it the Delaney amendment, and the unusual support of the tobacco companies that happened at that time.

CONIS: There are a few threads that tend up getting intertwined while all this is going on. The folks at EDF won their hearings in Wisconsin, the department ruled that DDT was a pollutant and recommended that it no longer be used.

They won another hearing in Michigan, and then they started getting invited to help file lawsuits all over the place. They were also tightly focused on DDT, and within a few years, they decided to petition the USDA and argue that because DDT, in effect, had shown up in women’s breast milk, under the Delaney Clause, its use needed to be halted.

The Delaney Clause was the 1950s bit of regulation that I mentioned before, which said that if anything was found to cause cancer in lab animals or people, it was no longer allowed in the food supply. In the late 1960s, in Hungary, some scientists had carried out studies using rats, where they showed that there was an increasing likelihood of tumors in rats that were fed DDT for subsequent generations.

When the folks at EDF found out about this particular study, they began to think, wait a second, DDT shouldn’t be allowed in the food supply under the Delaney Clause, and maybe we can get rid of it that way. This was one of the arguments filed in a petition with the USDA at the very tail end of 1969 and early 1970.

What is interesting is that the Delaney Clause was just at that time starting to come under fire from companies and industries, who found that it was getting in the way of their ability to do business. Because lots of things caused tumors in animals, in particular, and keeping all of those out of the food supply was going to mean pulling back on a lot of commonly used chemicals, not just pesticides.

So Delaney had a number of foes going into the 1970s. …One of them was a consumer group that was created in the late 1970s, the American Council on Science and Health, which was really focused on using its organizational might and the news media to undermine public support for the Delaney Clause, so that it would ultimately be overturned.

Long story short: if we fast forward to the late 1990s, actually 1996, the Delaney Clause ended up being undone, removed form the Food and Drug Administration. There is a much more complicated story about why – and why it happened at that moment.

But, to go back to your question about the tobacco industry, their feelings on DDT are pretty complicated at this time. Around the time that EDF and other community groups are seeking local bans, and then seeking to petition the U.S. government to consider pulling back on DDT, the tobacco industry is facing heat, because European nations are passing limits on the amount of DDT allowable in crops that they are importing. Some European journalists had done independent tests of America cigarettes on the market in Europe, and they found that [the American cigarettes] contained extraordinarily high levels of DDT.

So, as the Environmental Defense Fund and other environmental groups [such as] the Sierra Club and the Audubon Society are focused on trying to get DDT effectively banned by the federal government [around 1970], at the same time, tobacco companies are starting to get anxious that their product is not going to be able to be sold in Europe. I think it was Germany and Great Britain combined that comprised some 30 percent of U.S. tobacco exports. [The tobacco companies] started to pressure first the growers to stop using DDT, and later, regulators. They started asking USDA to ask growers to stop using DDT, but they stayed quiet about it. At the same time that environmental groups are seeking to halt the use of DDT, the tobacco industry is seeking the exact same thing.

In 1972, the U.S. federal government, in the form of the Environmental Protection Agency, which was newly founded, banned DDT in 1972, and the environmental groups claimed it as a victory. But when you kind of scratch the surface and look a little deeper, it becomes clear that there were other interests that wanted to see DDT go, and the tobacco industry was one of them.

Chemical companies were another; DDT was not a money maker for them anymore by this time, and they were happy to see it go, and to have farmers stop using it, and then they used that as an opportunity to start selling more expensive pesticides, particularly patented ones.

JAMES: I want to ask you a question about how you came to write this book. You haven’t talked about that yet. Why did you choose this subject?

CONIS: I am happy to talk about that. A few minutes ago, you described how I had described this book, in the introduction, as a story that unfolds in three acts.

Act One: we have this wonder chemical, DDT, and we embrace it whole-heartedly. Act Two: We ban it. Act Three: We haven’t talked about it yet, but in Act Three, which we will get to, begins in around 2000, when people start saying, it is time to bring back DDT.

That moment is why I decided to write a whole book about this. As probably has already become clear, there are so many threads, and so many complications, to DDT’s story.

I first became aware of it, right around the year 2000, when I was a graduate student in public health at the time, and I was attending a conference on global health issues.

At one of the panel discussions, the folks in the front of the room, the experts on global health, and they were talking about malaria, and particularly, how bad malaria had gotten in Sub-Saharan Africa, and how it was really important to consider bringing back DDT to combat this disease.

As somebody who was in gad school in the year, 2000, I had grown up hearing about DDT as this extraordinarily toxic chemical that was linked to cancer and that was implicated in the decline of the bald eagle and the peregrine falcon and the osprey, which had once inhabited the place where I grew up and were no longer there. So, in the year 2000, I found myself thinking: Why on earth would we bring this chemical back?

I know malaria is horrible. But don’t we have other tools for combating the disease at this point in time?

And, the question sort of stuck with me for a while. Years later, I was introduced to something called the Industry Documents Library, which is a collection of corporate documents from the tobacco industry, released in the process of discover during the suits against the tobacco industry during the 1990s.

And, these documents were collected and digitized by UCSF, and I was looking through the documents, and I something just made me plug DDT into the search engine.

The very first thing I came across was the fact that back in th e1940s and 1950s, tobacco companies had been studying DDT, because they wanted to know how it affected their crop. It actually made the tobacco kind of sweeter, and it affected the burn rate. But later on, I could see that they were becoming skeptical of [its benefits].

And so, that kind of stuck with me. I never really expected that there would be a connection between the tobacco industry and DDT.

I held onto that [nugget] for a few more years, and the Industry Documents Collection just grew and grew. A few years later, again, just one of those days when you are doing research, and you decide to plug in something random, and I plugged in DDT.

And, I came across this really curious document, from the year 1998, and in it, somebody was describing an idea for a campaign, and how the campaign would popularize the idea that it was time to bring DDT back into U.S., and that the argument for bringing it back was that it was the best way to control malaria in Sub-Saharan Africa.

But the point of the campaign wasn’t actually to control malaria; the point of the campaign was actually to cause a rift among advocates for the environment and advocates for public health, a rift among liberals and Democrats, to split them and to pit them against each other.

And, in particular, to show the quote unquote “hypocrisy” of the DDT ban to show that by banning this chemical, in the interests of Western nations like the U.S., it left poorer, impoverished nations in places like Sun-Saharan Africa at greater risk of malaria.

And, this was a campaign proposed by a think tank, a conservative think tank, and it ended up being funded by the tobacco industry. Which was why it was in the Industry Documents Library.

At this point, I realized that there was probably a book to be written, because there was far more to the DDT story than met the eyes.

JAMES: Has your opinion changed on whether, indeed, DDT might have saved lives internationally?

CONIS: That is a really good question. And, that was one of the other reasons why writing a book about this appealed to me. Because there are no easy answers in this story. DDT absolutely saved lives; it absolutely was harmful to wildlife, and it absolutely increased people’s risks to several different types of cancer, not just breast cancer.

So, it had extraordinary benefits and extraordinary costs, as most technologies do.