How will $20 million be divvied up to support the recovery community?

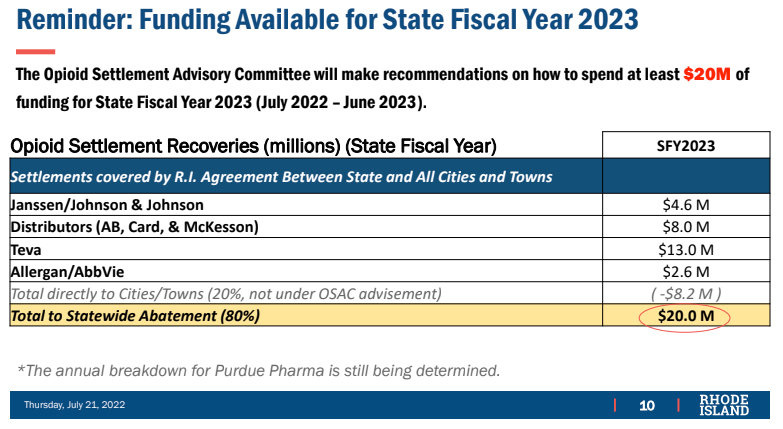

Thanks to the legal victories won by Attorney General Neronha, some $20 million in new funds will be disbursed in FY 2023

Sitting next to a young reporter from the Boston Globe at the forum, I was struck by how little of the history of the recovery community in Rhode Island – the narrative of what happened and the people involved – has been told. It would make a great oral history project for a student involved with the School of Public Health at Brown University to take on the task of compiling such a record, before it gets swallowed up and forgotten.

PROVIDENCE – It is a cliché to say, “What a difference a year makes.” Last year at this time, the R.I. Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities, and Hospitals, or BHDDH, was busy informing community agencies involved in managing recovery programs that the state agency intended to cut some $2.3 million in funding, as of Oct. 1, 2021.

The cuts – which Gov. McKee insisted, in response to questions from ConvergenceRI, were not “cuts” but the result of the sunset of several federally funded programs – had caught many of the community agencies off guard. Surprise, surprise, surprise.

On Sept. 6, 2021, in an exclusive story, ConvergenceRI broke the news of the pending cuts. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “BHDDH cuts more than $2 million in funding for recovery programs.”]

In response to the ConvergenceRI story, the recovery community rebelled and held an intervention two days later at the Sept. 8, 2021, Governor’s Task Force on Overdose Prevention and Intervention, leading to a walkout by task force members. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “Hard of hearing? BHDDH’s Charest and Gov.McKee seem to be tone deaf.”]

As a result of the intervention and walkout, the cuts were rescinded by the state. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “How the good guys and gals won.”]

That incredible story – the planned cuts, the intervention, the recovery community’s walkout, and then the rescinding of the cuts – was not covered by any other news media in Rhode Island, save for Uprise RI.

The difference made by having those cuts rescinded can best be told by the story of what happened with CODAC and its mobile medical unit. As ConvergenceRI had reported in its initial story on Sept. 6, 2021: CODAC had been slated to lose more than $1.3 million beginning Oct. 1, including $755,791 to provide medication-assisted treatment “induction” opportunities at BH/Link on a 24/7 basis.

In addition, the story continued: CODAC, the largest nonprofit outpatient provider for opioid treatment in Rhode Island, also received a $333,313 cut in funding for its efforts to develop its mobile treatment capacity [emphasis added].

The program was first developed as a shared mobile treatment unit for the opioid epidemic. It was then redeployed as a mobile COVID testing unit during the coronavirus pandemic. [See link below to the ConvergenceRI story, “A report from the front lines of telehealth.”]

Because of the challenges created in sharing the mobile unit, CODAC applied for and received funding from the Champlin Foundation to purchase its own mobile unit. Now, just as the mobile unit was about to be deployed, CODAC [was slated to lose] the funding for staffing through the cuts in state opioid response dollars from R.I. BHDDH.

Today, the CODAC Mobile Medical Unit is serving clients across Rhode Island, in communities such as Providence, Pawtucket, and Woonsocket. In Woonsocket, the vehicle is parked at Community Care Alliance headquarters, several mornings a week, from which it can distribute methadone to clients – one of the first such mobile programs in the nation. [See link to ConvergenceeRI story, “Investing in human infrastructure.”]

How important is the presence of the CODAC Mobile Medical Unit in Woonsocket? Last week, on Aug.10, a public health alert was issued for Woonsocket in response to an increase in non-fatal opioid overdose activity in the city, prompted by “an exceedance of the pre-established opioid overdose threshold in Woonsocket for a seven-day period, from July 31, 2022, to August 6, 2022.”

The alert continued: “There were six reports of individuals receiving care at an emergency department for a suspected opioid overdose; the weekly threshold is four.”

A big effing deal

Fast forward to August of 2022, and the announcement last week by the R.I. Executive Office of Health and Human Services on how it would be distributing approximately $20 million in funding through the Opioid Settlement Advisory Committee, obtained through the legal efforts by R.I. Attorney General Peter Neronha to hold the bad actors in the opioid epidemic – the manufacturers such as Purdue Pharma, the distributors such as McKesson, and the consultants such as McKinsey & Company – accountable for their misdeeds.

Translated, recovery community agencies that were once targeted for $2.3 million in cuts in funding a year ago by R.I. BHDDH are now slated to receive roughly 10 times that amount – $20 million – in FY2023, with more funds to come in subsequent years.

WPRI’s Ted Nesi tweeted on Wednesday, Aug. 10, “This is a big deal. The state has secured a ton of money through these opioid settlements and now must decide how to spend it all.”

“It is a very big deal,” Neil Steinberg, president and CEO of the Rhode Island Foundation, tweeted in response to Nesi. “We need to make sure allocation and actual distribution is done transparently and expeditiously to help those most in need! Prevention, education, treatment, workforce all imp.”

The problem, of course, is who controls the narrative of the story about “the big deal” – and how much credit goes to both the recovery community and to the Attorney General in telling what happened and why.

Innovative legal strategy

The fact that the legal settlements resulted in funds flowing back to cities and towns in Rhode Island and to community agencies and programs, focused on opiate abatement – and not put into the general fund account of the state – is by itself a remarkable sidebar to the story and the innovative legal strategy pursued by Attorney General Neronha. [See links below to ConvergenceRI stories, “Holding bad corporate actors accountable for their misdeeds,” and “The high cost of consulting firms making policy.”]

“This office engaged in years-long litigation against numerous opioid manufacturers, distributors, and consultants in courtrooms in Rhode Island and elsewhere for a single purpose: to hold those companies accountable for deceptively peddling highly addictive narcotics to Rhode Islanders and recover as much money as possible to fight the ongoing opioid crisis they caused,” said Attorney General Neronha, in the Aug. 9 news release announcing the planned distribution of the $20 million during FY 2023.

Attorney General Neronha continued: “I am grateful that that the Advisory Committee has begun to allocate the over $140 million this office delivered to Rhode Island for opioid prevention, treatment, and recovery. This is only the beginning, and I look forward to their continued work to allocate these funds in the most effective way possible.”

The recommended disbursal of funds will require the shepherding of the money through the state’s procurement process, stewarded by Ana Novais, the acting Secretary at R.I. EOHHS.

The recommendations were broken down as follows:

• Social Determinants: a total of $3.45 million, targeting $1 million for first responder/peer recovery specialist trauma supports, $700,000 for basic needs provision for high-risk clients and community members, and $1.75 million for housing capital, operating, and services for high-risk communities.

• Harm Reduction: a total of $4.5 million, targeting $1.5 million for expanded street outreach, including undocumented resident engagement, $2.25 million for harm reduction centers infrastructure and technologies, and $750,000 for alternative post-overdose engagement strategies.

• Treatment: a total of $2.8 million, targeting $500,000 for Black, indigenous and people of color [BIPOC] industry workers and chronic pain treatment and prevention, $1.5 million for bricks and mortar facility investments, treatment on-demand, and contingency management, and $800,000 for additional substance use disorder [SUD] provider investments.

• Recovery: a total of $2 million, targeting $900,000 for recovery capital and supports, including family recovery supports, $600,000 for substance-exposed newborn intervention and infrastructure, and $500,000 for recovery housing incentives.

• Prevention: a total of $6 million, targeting $1 million for enhanced surveillance and communications [e.g., race/ethnicity data and multilingual media, $4 million for school- and community-based mental health investments, and $1 million for nonprofit capacity building and technical assistance.

• Governance: a total of $1.25 million, targeting $500,000 for project evaluation, $500,000 for emergency response set-aside, and $250,000 for program administration.

The guidelines followed by the Advisory Committee for disbursing the funds included:

• Spend money to save lives

• Use evidence to guide spending,

• Invest in youth prevention,

• Focus on racial equity,

• Develop a fair and transparent process for funding recommendations

• Consider future sustainability in all recommendations

Sharing the wealth: guide for the perplexed

Exactly how the money will be allocated is a bit of a complicated process. Once the state procurement process has “approved” the spending of the $20 million, the next step will be figuring out how community agencies can apply for the funds.

As Kerri White, the communications spokesperson at R.I. EOHHS explained the process in response to questions from ConvergenceRI: “Procurement includes a variety of vehicles, such as Requests for Proposals, Request for Quotes, Requests for Information, Direct Purchases, Contract Modifications, Mini-Grants, and a host of other mechanisms – most of which are competitive processes.”

White continued: “Neither the Committee, nor the State, can designate funds for specific agencies in the way that the Legislature can within the state budget to individual organizations or the Rhode Island Foundation [can], for example.”

Because of this, White explained: “EOHHS is evaluating which procurement mechanism is best suited for each of the items of recommended funding by the Committee and will pursue the appropriate mechanism in partnership with finance and budget [team] at EOHHS as well as the Department of Administration.”

Further, White said. “Updates will be made at the Advisory Committee Meeting on progress and in a way that doesn’t violate purchasing rules.”

Speaking words of wisdom

In a recent article published on Aug. 14 in The Guardian, author Beth Macy, who wrote Dopesick, which was turned into the series of the same name, streaming on Hulu, which has garnered 14 Emmy nominations, talked with reporter Edward Helmore about her upcoming book, Raising Lazarus, scheduled to hit the bookstores this week.

“At this point, too much attention is focused on stemming the oversupply of prescription opioids,” Macy wrote, as quoted by Helmore. “We now have a generation of drug users that started with heroin and fentanyl.”

Helmore described the changing landscape of addiction as follows: “Fentanyl manufacturing runs from precursors sourced in India and formulated in China to distribution via Mexico to the U.S. What used to come in labeled plastic pill bottles with child-proof lids now comes in 50-gallon drums.”

As Helmore recounted, when Macy asked a group of substance users in Charleston, West Virginia, what would help them the best, they told her they wanted an end to police brutality, a place to shower, and friends.

“I thought, Wow, that’s not exactly the solution you’d think would be first, but it is this idea of listening to the people who have been most harmed by this issue,” Macy said, as Helmore reported in his story.

“We’ve been blaming the wrong people,” Macy said, as reported by Helmore. “We’ve been blaming the people that Richard [Sackler] wanted to hammer – the abusers. If we can switch the blame to pharma, political enablers and lobbyists, then we can begin to have empathy – which is what it’s going to take – to reduce the stigma to actually begin to deliver treatment at a scale to match the scale of the crisis.”