In pursuit of dragon smoke

A 1987 interview with the poet Robert Bly

So it seems in the last two years, we have drunken some darkness and so become visible as we grapple with the trauma of a global pandemic, as a kind of “Let’s Make a Deal” episode where we are fighting to keep the light shining.

There are voices to be heard these days – women writers such as Rebecca Altman, Sandra Steingraber, Bathsheba Demuth, and Kerri Arsenault that provide us with an alternative narrative to our lives outside of the corporate mainstream, that mix science, politics, and activism in a new kind of storytelling, poetic in its turn of phrase, haunting in its ability to connect and braid our lives together. Can you hear it? Are you listening?

Editor’s Note: In March of 1987, I conducted an interview with the poet, Robert Bly, who performed at a coffee house in Northampton, Mass., the Iron Horse. I had first become familiar with Bly’s work as a translator, in a book of translations of Pablo Neruda and Cesar Vallejo’s poetry.

Bly died on Sunday, Nov. 21, at the age of 94, and it seems appropriate to re-publish the interview, in similar fashion to my re-publishing the 1976 interview I did with Toni Morrison, following her death in 2019.

Bly’s pronouncement following the 1987 reading, in an interview, still captures a basic reality about American life:

“Americans like to be lied to. We are still living in a Doris Day movie in which everything we do works out.”

In the same manner in which Stephen Sondheim, who also died last week, wrote the quintessential American songbook for theatre in the second half of the 20th century, Robert Bly connected the political to the poetic in verse.

NORTHAMPTON, Mass. – Robert Bly is the kind of poet who is not loved nor admired by university creative writing professors. The disaffection is mutual.

“American poetry,” Bly complains, “has gotten very tame, like tame dogs. I blame it all on the universities.”

The problem, he said, “is that everything is very horizontal. No spirit, no soul. All we have is The American Poetry Review.” And he wonders aloud how they manage to find so many bad poems.

Poems, Bly believes, are reservoirs of the soul. But compared to the hard, precise lines of the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova. “…most American women are writing Hallmark greeting cards and the men are writing Valentines.”

Instead, the white-haired poet, translator and shaman from northern Minnesota seeks out “dragon smoke” – what he calls the leap in poetry that moves from the conscious to the unconscious – and back again. My poems, he explains, “go inside the psyche and find out what's inside.”

It was definitely dragon smoke that swirled about the Iron Horse Cafe in Northampton, Mass., on March 10, marking the last reading on Bly’s recent two-week tour of the Northeast, with stops in Worcester, Mass., Binghamton, N.Y., and Philadelphia.

And Bly, wanting to make sure that the audience traveled with him as he performed his verbal acrobatics, asked first that the spotlight on him be dimmed and the lights on the audience brightened. He took off his shoes, to make himself comfortable, and strummed on his bouzouki, a Greek stringed instrument he plays like a dulcimer.

Often Bly read a stanza two or three times, relishing in the repetition and asking the audience, “Is that clear? Do you understand?”

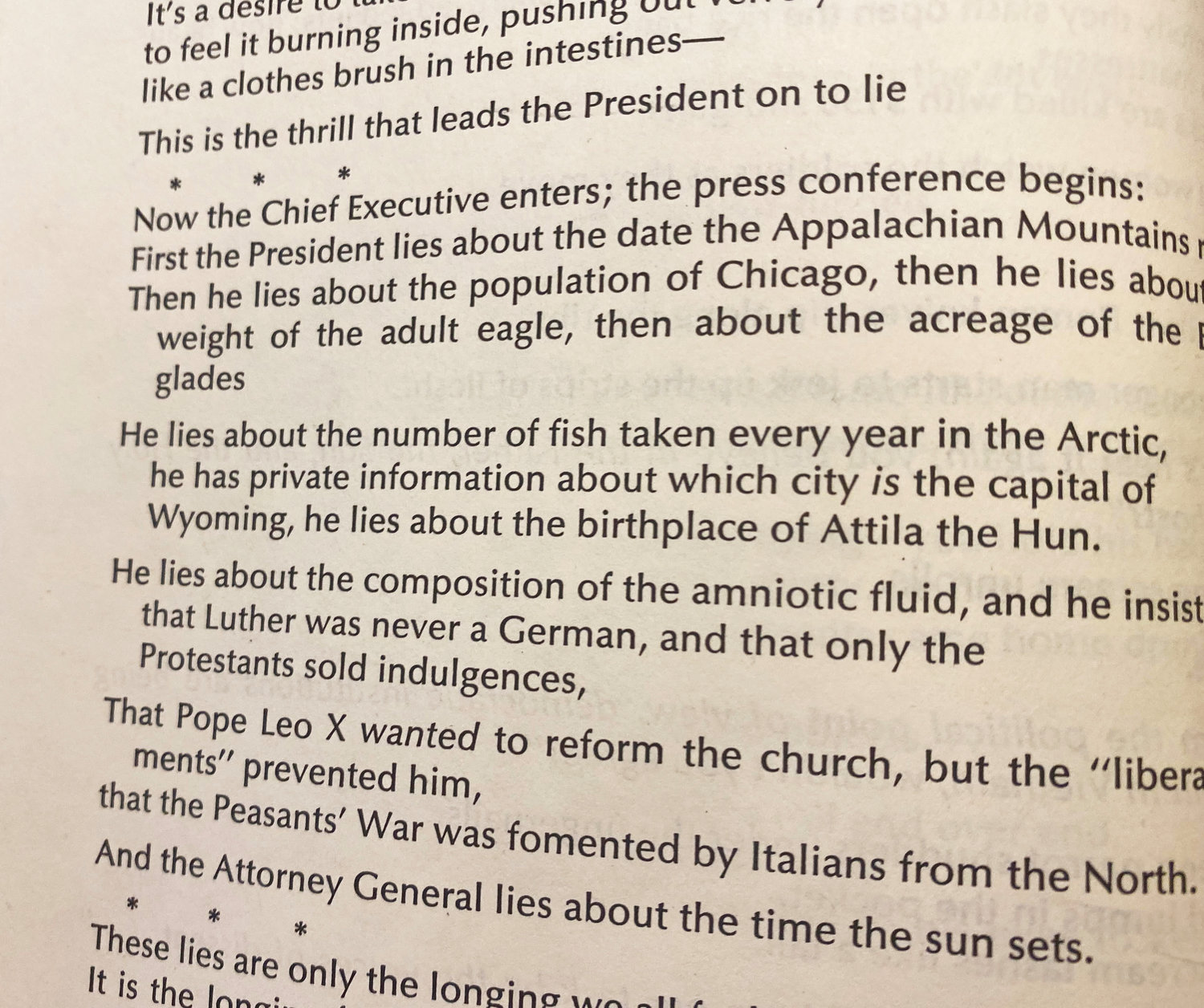

Bly introduced a poem he [began writing in 1967 and first published in 1970] after listening to a Vietnam press conference by President Lyndon Johnson. At first, Bly takes us back 20 years, as his gravelly voice mimics Johnson’s Texan drawl, and then, we are transported to a family farm in Minnesota, where Bly confronts his own father’s alcoholism, and then we are listening to President Ronald Reagan, refusing to admit that he lied about trading arms for hostages.

“My father was an alcoholic,” Bly intones. “Ronald Reagan’s father was an alcoholic, too.” Bly recalled his father’s smile in denying he was an alcoholic, then said of Reagan: “I recognize that smile now.”

An intervention

The entire country, Bly continued, is trying to do an intervention with Reagan, and he tells the story of an intervention done for a colleague, where all the friends and family gather in one room and confront the alcoholic, trying to force him to admit to his drinking problem. Then we are back with Reagan.

“Try it again,” Bly says, as if we are all in a room, talking to the President. “See if you can admit that you are a liar.”

Then we are launched into the poem, Johnson’s lies mixing with ad-libbed lines about Reagan’s untruths. The poem ends with: "Attorney General Meese lies about the time the sun sets."

“Americans like to be lied to,” Bly said in an interview after the reading. “We are still living in a Doris Day movie in which everything we do works out."

The prosaic vegetable garden

Bly says he’s not political as much as he is a traveler into the psyche. And, quick as a minnow darting away into the shadows, Bly transported the audience from an intervention with Reagan to the prosaic vegetable garden. He read a prose poem about his cucumbers wilting: The cucumbers are thirsty… So much is passing away, so many disciplines are already gone. To those waterers who love your garden, how will you get through this night without water?

Much of Bly’s recent work, like Neruda’s odes to elemental things, has focused on objects – a grain of rice, a potato, a flounder – and on simple acts like peeling an orange.

The poem about the grain of rice started as a class exercise. “I gave them a single grain of rice, and then, after 30 minutes of writing, I asked them to compare it to the quarter-moon,” he says. The exercise, he explains, “was an attempt to go sideways into an object, to try and write about an object with all your attention and discipline. A lot of time,” he said with a laugh, “nothing happens.”

Bly admitted that he has been rewriting [his own] rice poem for five years. In the work, the rice grains become as children:

Each child

is a grain

of engendered light

threshed from thousands

of feathery plants…

In the same way,

our own children

will not dissolve…

Then, like a gentle breeze, Bly shifted to a love poem. He began with an apology. “Love poems go out of tune so easily,” he says. “One of the problems is that if you stay really close to your feelings, the woman disappears. And if you stay really close to the poem, the feelings disappear.”

But the verse he reads is far from hopeless:

Every breath taken

by the man who loves

and the woman who loves

goes to fill the water tank

where the spirit horses drink…

“It’s difficult,” he says, “to have a true love affair in your 20s because you haven’t been wounded enough.”

A father's remoteness

The most resonant poem of the evening was a recent verse Bly wrote for his father while the elder Bly was in the hospital recuperating from pneumonia. Bly had never written a poem in front of his father before, and he found the experience revealing.

The poem has a “thinness” of lines, Bly explains, because “there is some kind of inflation in every long line, and I wanted to be naked with my father.”

Some powerful

engine of desire

is inside him…

He never phrased

what he desired

and I am his son.

The remoteness of the father from the son-a situation caused by the Industrial Revolution, according to Bly, which took the father out of the home, means that a young male is never taught about his own maleness by his father. All too often, Bly says, the teaching is left to the mother, and a woman “cannot teach a young boy about being a man, no more than a father can teach a daughter about being a woman.”

Editor’s Note: The interview was first published on April 13, 1987, in The New Haven Advocate.