Love your mother

To celebrate Earth Day, the true story of how DDT was marketed, sold, regulated, and then resold to the American consumer

What would stand out in a retrospective analysis, looking at the apparent poor policy decisions made by Lifespan under Babineau’s leadership? Would it link how Babineau’s arrogance and hubris often led to a number of wrong-headed policy decisions? They might include: Lifepsan’s attempt to set up its own birthing facility in competition Women & Infants Hospital; the recent acquisition of Coastal Medical as a way to minimize the health system’s own failure to build out its primary care service delivery; the difficulties in maintaining a sustainable nursing workforce; and the health system’s failure to develop a collaborative model to support community health centers to avoid unnecessary emergency room visits, among others.

Such an analysis might also examine the ways in which Rhode Island’s news media – including The Providence Journal, Providence Business News, and WPRI – provided Babineau with unfettered access.

Editor’s Note: This Friday, April 22, will mark the 52nd celebration of Earth Day, when citizens attempted to wrest control of their own destiny under the simple but elegant slogan, “Love your Mother,” using a photograph of our blue orb taken from space.

Today, the Earth appears to be on its last exhale, pushing out a long, long note. Can you hear it?

The story of what happened – and why – is still being written. Courageous writers, scientists and activists are still battling against corporate and political forces to prevent wholesale catastrophe.

All the signs, from the melting of ice shelves in Antarctica to the rising temperatures in our oceans, from the increasingly violent storms disrupting our weather patterns to the proliferation of plastics in our oceans and rivers and in our own bodies, point to irreversible changes and threats.

There are many among us who persist in persisting, in keeping on keeping on, and, in the face of cynicism and corruption, to forge a better world – and a better neighborhood.

To do so, it requires changing the narrative. To change the narrative, it requires telling the stories of what happened.

In honor of Earth Day, here are four such stories.

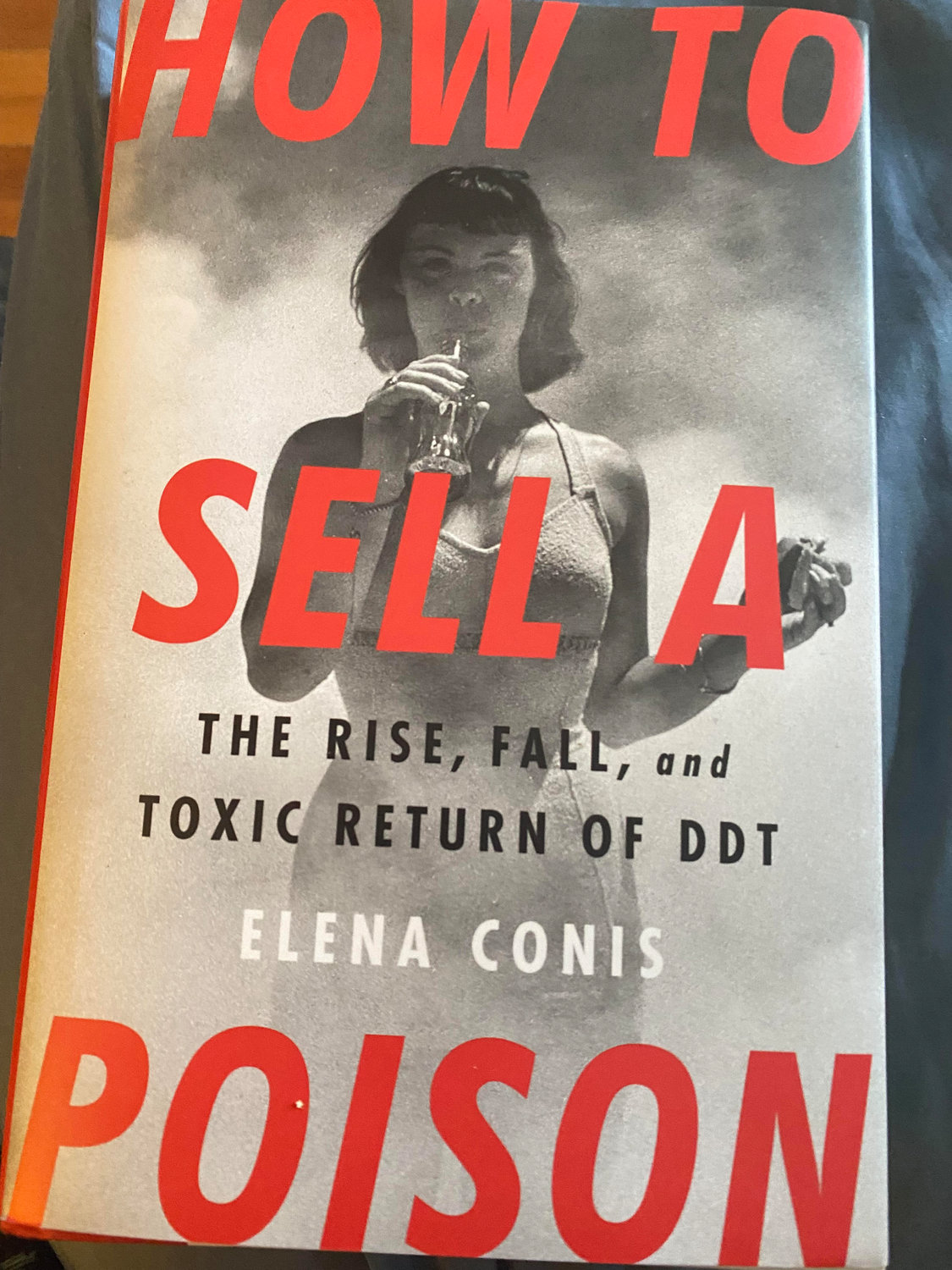

• The first is about DDT as told in a new, provocative book, How To Sell a Poison, by Elena Conis. The book knits together what happened with DDT, how it was marketed to the American public.

• The second is the transcript of an in-depth interview with Conis, who, much like writers Rebecca Altman, Kerri Arsenualt, and Bathsheba Demuth, is constructing a new narrative about the world around us.

• A third story delves into the latest revelations about the collusion between McKinsey & Company, the FDA and Purdue Pharma.

• A fourth story poses some impertinent questions about the proposed plan to resuscitate the Industrial Trust building in downtown Providence, through an environmental lens.

PART One

PROVIDENCE – There was a moment in the saga of the planned resurrection of the Industrial Trust building, the iconic art deco structure known as the “Superman building” where a spokesman said on Twitter that the nesting of the peregrine falcons atop the edifice will be maintained and preserved in the plans to transform the now-vacant structure into a residential enterprise.

But the return [and preservation] of the peregrine falcons, like the return of the ospreys to Rhode Island, has much more to do with the decision to ban the use DDT in 1972, a ubiquitous, toxic pesticide developed during World War II.

The story of DDT and its successful marketing to the American people is captured in a new book, How To Sell a Poison: The rise, fall, and toxic return of DDT, by Elena Conis. Rachel Carson, in her book, Silent Spring, had documented the adverse environmental effects caused by the indiscriminate use of pesticides such as DDT. In her book, Conis tells the story in three acts – the marketing of DDT, the attempts to regulate the pesticide once the damages became known, and then the corporate efforts to resurrect DDT.

The provocative cover sleeve for the book features a photograph of a model, Kay Heffernan, posing on Jones Beach, in a fog of sprayed DDT, eating a hamburger and drinking a Coke from a bottle, an image taken from an article published in LIFE magazine in 1948, in what would be described today as “sponsored content.”

A manufacturer of industrial fogging machines developed to create smokescreens to hide troop movements during World War II was attempting to capitalize on developing a new market opportunity – the use of its fogging technology to spray DDT for the purpose of killing flies, which were falsely alleged to be the source of how the dread poliomyelitis virus was spread. In numerous communities across the U.S., the spraying of DDT to stop outbreaks of polio by killing flies became accepted public health practice. The aerial spraying of DDT did not halt the spread of polio, but it did lead to a new “disease,” known as virus X, which was later confirmed to be the result poisoning from DDT.

The ways which “science” became a political football – with competing narratives influenced by corporate agendas, bears an uncanny resemblance to our current-day struggles with the coronavirus pandemic and the struggles between public health and behavioral economics.

A model’s breast as metaphor

Here, in PART One, in an extended Twitter thread, the author Elena Conis, a historian, described her initial reaction to the decision by her publisher, Bold Type Books, to suggest she use the photograph on the cover, which at first she disliked and opposed, because it seemed to be using sex to sell her book.

In her thread on Twitter, Conis shared how she changed her mind: “I confess that when I first saw the cover, I wanted to reject it,” Conis tweeted on March 24, in a pinned tweet.

“Looking at it, all I could focus on was her left breast, which seemed to pop off the page in high relief. Yes, she’s surrounded by DDT. And I know sex sells. But did I really need to sell my book with a babe?” Conis continued.

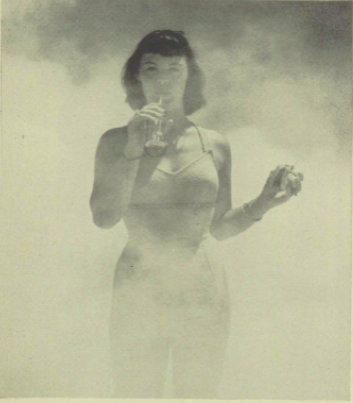

“I wanted to build an argument against the cover, so I tracked down the photo in its original context. Here it is.” [See second image.]

Conis then explained the context for the image: “The photo is from what appears to be an article in Life magazine, 1948. Today, we’d call it sponsored content – it’s an ad. It’s selling an industrial fogging machine, first designed to create smokescreens used in WWII.”

The provocative photo of the woman model in a bathing suit was a way to sell the fogging technology, Conis continued. “In the late 1940s, the manufacturer wanted a new market for its machines. A series of devastating polio outbreaks provided a chance. Capitalizing on a then-popular theory that flies spread polio, they sold the foggers as a way to kill all flies in a town.”

DDT was safe, regulators promised, as Conis continued with the story. “They promised it wouldn’t harm bees. They promised it wouldn’t contaminate food. They were wrong. Yet their promises helped make a cloud of DDT seem like one of the safest places to be.”

Conis returned to the image of the model’s breast that seemed to protrude out of the fog. “But back to the breast. By the time of this photo – when this woman was fogged in DDT – FDA scientists knew DDT accumulated in fat and showed up in breast milk. They didn’t know what that meant, and that worried them. They warned against DDT’s indiscriminate use.”

The other government agencies discounted the FDA’s warnings, according to Conis. “The FDA’s counterparts at the USDA, however, insisted DDT was safe. So did scientists at the CDC.”

Decades later, the scientists at the FDA would be vindicated, Conis continued. “Eventually, the FDA team would be vindicated – but not for decades. And by then, their warning was long forgotten [or rather, drowned out by a combination of Army imperatives, CDC and USDA scientists, and corporate PR].”

But not before the pesticide industry was churning out a hundred million pounds of DDT a year. “By 1960, manufacturers were churning out roughly 100 million pounds of DDT annually. And DDT was only the most famous of a larger class of insect-killers, being produced at a rate of half a billion pounds a year.”

At the same time, breast cancer rates were soaring, Conis continued. “All the while, cancer rates soared. Breast cancer rates rose more than 60 percent in the 1970s and an additional 30 percent in the 1980s. Women began asking scientists to look at the connection between the disease and environmental chemicals, including DDT.”

The links between DDT to breast cancer were confirmed by new studies, according to Conis. “In the early 1990s, new studies linked DDT to breast cancer. The link was contested for the next two decades. Today, it’s increasingly accepted. But some of the strongest evidence suggests the risk is greatest for women exposed to DDT when young.”

Which brought the story back to the cover photo, as Conis explained. “That’s why Kay Heffernan’s left breast isn’t just a racy reminder of the ways companies use women’s bodies and the promise of youth and beauty to sell us everything—including literal poisons. It’s a cruel irony.”

What happened to the model remains an untold story, Conis said. “I'm not certain what happened to Kay Heffernan, the model fogged by DDT. Maybe she left modeling; maybe she married. Maybe she moved; maybe she had a family. Maybe she got breast cancer; maybe she escaped the disease.”

Which led Conis to decide to keep the racy photo on the cover of her book. “No matter what became of the rest of her life, it’s impossible to look at her image now as anything but a young woman, surrounded by an ominous cloud of poison – as unaware as the rest of us about the danger it might be inflicting on her body. Her story is our story. So I stuck with the cover.”