To showcase 3,800 hidden treasures

The University Museum of Contemporary Art at UMass Amherst opened its gallery to display 112 pieces of artwork that are part of the museum’s permanent collection, including works by Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Jasper Johns, Allison Saar, and Roni Horn, among others

Hours: Open Tuesday - Friday, 11 a.m. - 4:30 p.m.; Saturday and Sunday, 12 – 4 p.m.

University Museum of Contemporary Art

University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Curated by Loretta Yarlow

In order to create a more place-based reality that tells the stories of our lives, one where we see ourselves as part of a neighborhood, and not just isolated in our cars or talking at each other at platforms such as Twitter, requires a different kind of participation. It may require an injection of kindness into the narrative of storytelling about our lives.

AMHERST, Mass. – The descent through walled concrete plazas, broad ramps and flights of steps to the museum’s entrance recalls the era of the 1970s, when students milled in protest around the fortress-like Brutalist architecture of the academy. Today this stony, sun-baked expanse could easily be a skateboard park.

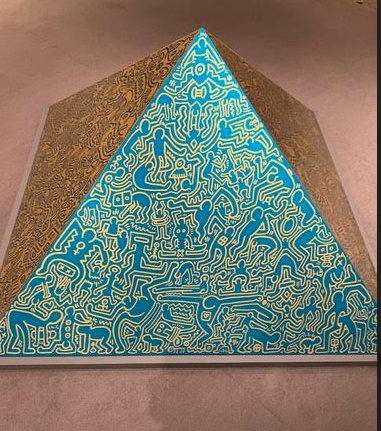

Visitors leaving bags and backpacks at the corner and stepping inside nearly tumble over Keith Haring’s low-slung aluminum pyramid, a maze of dancing and writhing figures shimmering in teal and gold.

Ryan McGinniss’s silkscreened enameled skateboard, lush with vegetal curlicues, hangs from a peg temptingly within reach. These and many other objects and images, so dynamic and alive, so full of movement, grace and feeling, as much as any from the more distant past, also count as art.

On the early October afternoon of my visit, as will be true on many afternoons until the exhibition closes in mid-May of 2023, moments of stillness and bursts of color draw the viewer through and around the museum.

A repeated theme among the exhibition’s scores of works yielding constant surprises is the strategy of doubling, folding, mirroring and reversal – often within the work, but frequently also in the manner or concept of display.

Alison Saar’s sewn lithograph, near the main entrance, is a flip-flop image of an African and a White woman above and below ground, connected by the feet and through a system of roots and veins to each other’s breasts.

It’s serendipitous but hardly unplanned to find, deeper in the galleries, a lithographic print by the younger artist’s mother, Bettye Saar, also containing a symmetrical pairing of two women, but this time face to face. [True to the Museum’s teaching function, Alison Saar’s work was selected for the UCMA’s acquisition by a recent vote of UMass students.]

Annette Lemieux has doubled and folded two identical but reversed images of a phalanx of soldiers so they appear to be marching away from each other in opposite directions. Over this she has also doubled and folded the phrase “forward and back.” As if split in half by a mirror, this text enacts its own simultaneous “march” forward and back, coolly challenging us to contemplate the repeated patterns of violence in a world immune to change.

Looking at more traditional landscape and documentary photographs, we still have to consult our knowledge of the world, the photographic process, and the artist’s possible intentions to interpret what we are seeing and why it matters.

Could Roni Horn be pulling our leg by twinning two photographs that appear identical but were actually taken “before” and “after” the interval of a geyser’s eruption? We understand them to be unique evidence of geologic time passing only through our knowledge of the fact that every successive photographic moment records the energy of different photons of light hitting a responsive surface.

A dual presentation in another room elicits different perceptions of time elapsing as lives are lived in relation to dwelling places. In Carrie May Weems’s black and white photograph of a woman [perhaps herself] contemplating an urban view of a Roman hillside, we witness the contrast of newer buildings that have piled up over ancient ones in the course of millennia.

It clashes sharply with an oversized color photo by Kwezi Naledi – a contemporary South African wasteland of rambling, half-built concrete homes – documentation of a failed model village that was never populated.

A pitch-black screen-print by Andy Warhol glitters with diamond-dust. It offers a one-two punch of materials and content, enticing us to make out faint rows of silhouettes of ladies’ stiletto heels.

A pure white rectangle by Dorothea Rockburne on the opposite wall – merely a sheet of paper folded, inked with a bit of white paint, and run through a press – is equally subtle and inscrutable. Significant marking of the “flat” surface is achieved, in addition to paint and pencil line, by scoring, faceting and buckling – deformations inherent in the paper’s material nature.

We find pathos as well as not-so-strange bedfellows in a pairing of large monochromatic lithographs by Jasper Johns and his former love, Robert Rauschenberg; the one’s morass of leaden murk contradicting the other’s whiz of race cars, light, wind and speed.

More questions than answers

Beyond charmed, I am bubbling with more questions than answers. Whose thought process besides my own has been operating under the surface to enable these perception, comparisons, and insights that keep on coming?

I need to find this out from the curator herself, Museum Director Loretta Yarlow. [Editor’s Note: The following interview with the Museum Director has been lightly edited for clarity.]

The University’s teaching collection of “3,800 hidden treasures,” Yarlow tells me, grew from a small cache in 1962, when drawings by Tom Wesselman and Claes Oldenburg were easily affordable. By 1975 the works on paper had expanded to include prints, drawings, and photographs.

“It’s local, regional, national and international art,” Yarlow said. “We bring artists from around the world, often for first-time exhibitions, and we also reach out to audiences on a global level.”

Yarlow praises the crisp geometric constructions in primary hues by Venezuelan sculptor, Jesus Rafael Soto, gathered on walls and tables across from the museum’s entrance.

When first researching the collection, she’d been amazed to discover five chromatic sculptures and several minimalist prints by this major 20th Century artist. “He’s one of the earliest kinetic artists. MOMA has large-scale sculptures of his, and here’s something at this museum that’s never been on view here in our community.”

MICHELMAN:I feel a particular visual sensibility throughout this exhibition. Did you put individuals in charge of different rooms, or was it teamwork all the way?

YARLOW: It’s my vision, but I have a great group of people working with me. My staff and I are four and a half people. In the North Teaching Gallery, we turn the space over to grad students from different disciplines who curate from the collection and find a theme – currently Transportive Art.

We have interns as well as student educators who get course credit. They get to see what large-scale museums do, but here on a smaller scale. This is my first opportunity in my UMass history to really think about this collection. Up until now, I’ve left the collection curation to grad students and local artists. I felt this was my chance to present my point of view as to what this museum’s collection is all about. It’s eight exhibitions in one large exhibition. I found thematic and formal threads and interwove them throughout.

Since I arrived, I’ve felt we’ve got to share it and care for it. This was my moment of letting it be known what amazing works are hidden away. We need to keep it up for a full academic year so we can do a robust educational program. If we never ever did another temporary exhibition, we could just stay with this collection, because we are hoping to grow it.

I want new interpretations. That’s what a teaching museum is all about —for people to bring a new understanding to art that they thought were household names. Andy Warhol, he’s in the pop art section; I also put him in the art and politics and photography sections. How many people know he was very vocal in the Civil Rights movement with his images?

He was a major photographer, keeping the camera around him at all times. He photographed a lot of “The Factory” people in their drag costumes. They could have been arrested back then. I mean, “Rethinking Andy Warhol.”

How many museums other than the larger metropolitan museums can do this? But we were nimble, and here’s our chance. I wanted to go into depth with pop, minimal and conceptual art. So much of art today is based on that “art of the idea.” I wanted to lay this foundation as a springboard for where we go from here.

MICHELMAN: Where is the “art of the idea?” Is it in the political section, largely?

YARLOW: Many students think “art of the idea” began with recent political events, but it really began with Conceptual art, concept art. If you look back at some of the art in the Minimal and Conceptual movements Sol Lewitt starts with an idea, a mathematical formula – a way of bridging color and line together – which may not have a lot of repercussions in the world outside us, but it’s a way to focus our vision, to settle us into a way of understanding. It can have a ripple effect.

There’s Dorothea Rockburne, who’s 89 years old. She was very well-known in the 1970’s. We only have one work in the collection, that folded white paper. I have a beautiful quote of hers where she talks about how a simple idea, the color of white, has so much in it.

MICHELMAN: It’s strange that changing fashions push movements aside, while the artists are still producing their art and developing, I’m thinking about Olivia Bernard’s show up in Greenfield.

YARLOW: I first heard of Olivia through her sculpture and was blown over when I first came to the community to make a studio visit. We have two beautiful works of hers in the collection, work on paper. It’s sculptural; it still fits into her sensibility. I feel it just sings on the wall. It’s another side of her vision that we’re able to bring to public attention.

MICHELMAN: I’ll be giving that attention, too. I’ve always known her two-dimensional and her three-dimensional work go hand-in-hand, but now I’m looking again and wondering, “How”

YARLOW: Mary Ijichi came in from San Francisco to join Olivia in our “Artists on Artists” gallery talk on Nov. 9, 2022. Mary’s piece, String Drawing, is that 12-foot-long scroll-like work on the wall that goes out onto the floor, pastel colors. It’s like Olivia’s, like skin. It was donated to the collection in the 1980s. It’s a very meditative piece in the way she creates it.

We got funding to bring her here to meet with students, go to some classrooms, and do this public walkthrough. It will be another way to get her ideas out there.

MICHELMAN: Accepting donations must be important for acquiring art within a public university’s budget. Does the collection’s focus on multiples also relate to budget?

YARLOW: We do accept donations. An acquisitions committee works with me as gatekeepers. We’re open-arms to hear what people might want to donate, though we do have specific needs and specific constraints with storage. The early collection was essentially drawings. They could bring it out and have students look at it in a seminar room. To bring out a sculpture or a painting… it would have been a storage issues, but also, how do you use it as a teaching tool?

The multiples come from a larger edition. The Soto was from an edition of 500. So we felt, OK, it’s a democratic process.

And why diverge from our focus in the 1960s, when we have such treasures in that area? A Joel Shapiro drawing [half-donated from the artist, half from our acquisition fund] is one fraction of the price of a sculpture. A drawing by an artist can be as potent as a painting or a sculpture, if that’s an area they’re working in.

Editor’s Note: When the show reopens for viewing on Tuesday, Feb. 7, 2023, it will feature a work by renowned artist Kiki Smith, on display in the “Regarding Landscape” section. The artwork was selected by students who are enrolled in Colleting 101. The acquisition was funded by an endowment recently established in memory of Lois B. Torf, one of the museum’s key donors.

This story previously appeared in Artscope Magazine in a slightly different version. It is reprinted in ConvergenceRi with permission of Artscope and the author, Elizabeth Michelman.