Uncovering the lost women of the Manhattan Project

An interview with Katie Hafner, co-producer of a podcast series that explores the women of science whose stories have been lost and not been told

PROVIDENCE – The latest episode in the podcast series, “The Lost Women of Science,” featuring chemist Lilli Hornig, “The Story of the Real Lilli Hornig, the Only Female Scientist Named in the Film ‘Oppenheimer,’” dropped on Thursday, Aug. 17.

“Lilli Hornig was only 23 years old when she arrived at Los Alamos to contribute to the development of an atomic bomb that would end World War II,” the written introduction to the podcast began. “A talented chemist, Lilli battled sexism throughout her career and remained a steadfast advocate for female scientists like herself.”

The written introduction continued: “Lilli is the only female scientist named in Christopher Nolan’s film, “Oppenheimer.” But the character is a blur, popping up here and there to say they didn’t teach typing in her graduate chemistry program at Harvard, when asked whether she could be a typist, or to rib a colleague, telling him that her reproductive system was better protected from radiation than his.”

The real Hornig, the written introduction concluded, “worked closely on plutonium research and was part of the tam that developed and tested the mechanism for the plutonium weapon in the Trinity test.”

For Katie Hafner, the co-producer of podcasts, the “Lost Women of Science,” which she launched in November of 2022, the idea of a new sideshow, creating the “Lost Women of the Manhattan Project,” was a natural tangent connected to her ongoing work.

In describing her approach in a 2022 interview with ConvergenceRI, Hafner said: “I think of every single one of those women whose names we have collected. We have a database right now between 150 and 200 women and that is growing, who deserve more recognition for the part they played in this or that scientific achievement.” [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “We are our stories.”]

Hafner had spoken with passion about the goals of the podcast: “Our mantra is that for every Rosalind Franklin out there, whose story has been told, there are scores of women who might not have done something as dramatic as discovering the structure of DNA, or played the key role that [Franklin] played with her x-ray crystallography; however, they are out there, having done amazing things.”

The first woman scientist featured in Hafner’s podcast was Dorothy Andersen, who identified and defined the disease, cystic fibrosis, the podcast documenting the enormous hurdles she faced.

“These are women who faced huge odds,” Hafner told ConvergenceRI. “Think about it. Being a woman is one thing. She went to Mt. Holyoke. We have these women’s colleges to thank in huge part for teaching science, early. But they often went into teaching instead of research science. But Dorothy didn’t. She went on to medical school. And, she was basically shut out of surgery, which is what she wanted to do. And so, we actually have all that discrimination to thank for the fact that she became a pathologist, because of her crazy, smart mind.”

The latest ConvergenceRI interview with Katie Hafner took place in the early evening of Thursday, Aug. 17, as Hafner was busy preparing dinner, rinsing greens. Her husband, Dr. Robert ‘Bob’ Wachter, MD, chair of the department of Medicine at UCSF, listened in, their dog barking in the background.

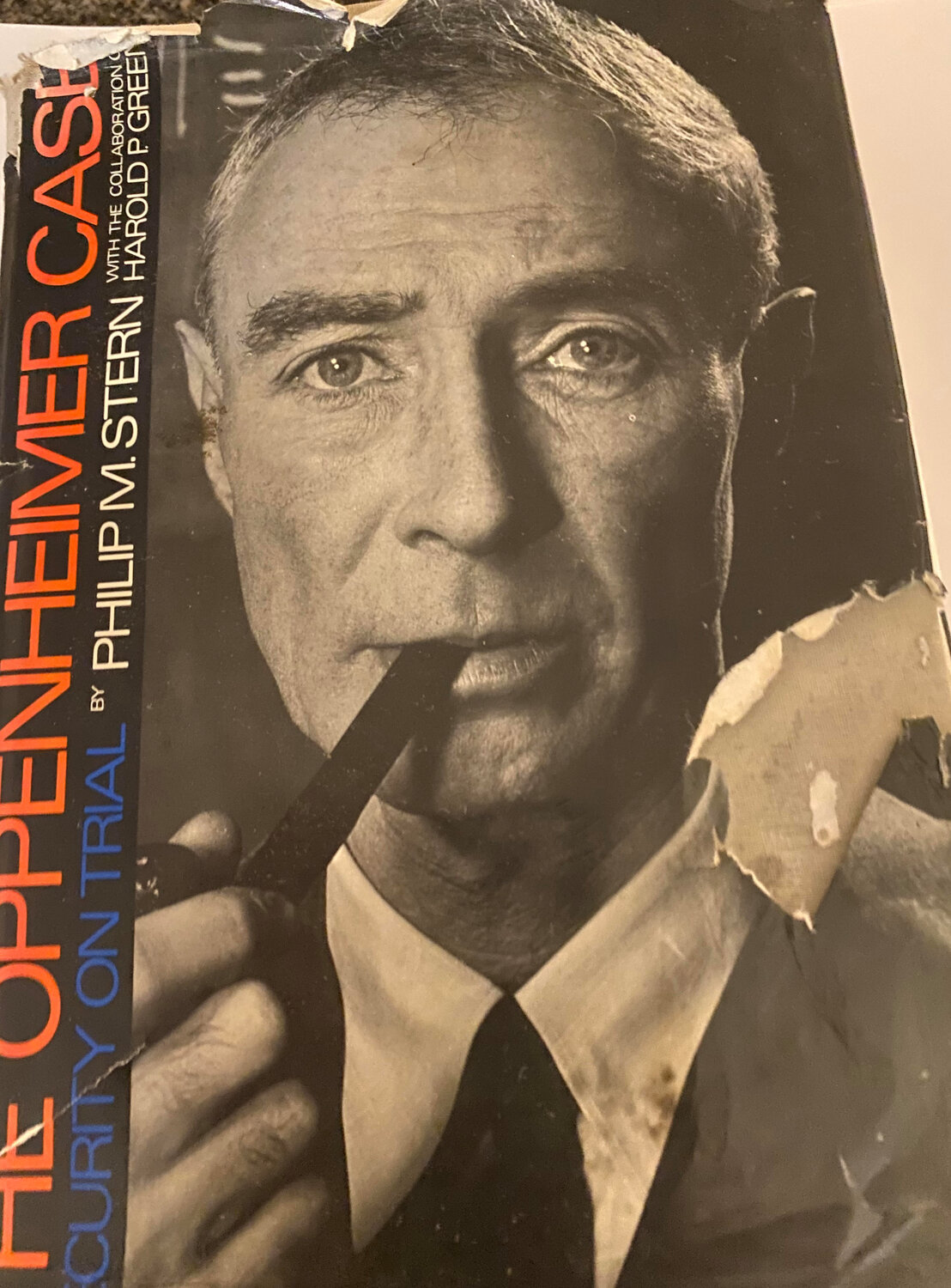

Hafner and ConvergenceRI had their own serendipitous story of convergence. Her father, Everett Hafner, had been one of the original professors at Hampshire College, where ConvergenceRI had been a member of the first class in 1970. Everett had taught a class focused on the security trial of J. Robert Oppenheimer, which ConvergenceRI had taken. The class used a book written in 1969 by Philip M. Stern, The Oppenheimer Case: Security on Trial, as the text.

The class explored the legal battle over the government’s attempt to withdraw its security clearance for the scientist, in 1954, ruling that Oppenheimer, who had directed the team of scientists that had developed the atomic bomb at Los Alamos in 1945, now represented a national security risk.

A new kind of emotional physics

The juxtaposition of two movies this summer, “Oppenheimer” and “Barbie,” provide the launch pad for a new kind of emotional physics, where stereotypes about men and women in science and in popular culture appear to grapple with ever-changing cultural goal posts and political calculations.

The lack of inclusion of women – and women scientists – in the movie retelling the tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer and how he was denied security clearance in 1954, after directing the successful construction of the atomic bomb in 1945, should not really surprise anyone.

In turn, the caricatures of Barbie [and Ken] offered a surprisingly insightful portrayal of breaking down the boundaries between gender roles and expectations.

Here is the latest ConvergenceRI interview with Katie Hafner, co-producer of the podcast, “The Lost Women of the Manhattan Project,” talking about what her latest research into the “lost women of science” has uncovered.

ConvergenceRI: What was the impetus for your expanded podcast on “The Lost Women of the Manhattan Project?

HAFNER: It was actually a suggestion by someone else, who said back in April or May, when Amy, my co-executive producer, and I were talking to him, and he said: “This new movie is coming out about Oppenheimer, and I have heard that there were not that many women in it.”

And, I said: “Oh my gosh, you are probably right.” That was that.

I said, “Let’s do a whole series.” Little did I know how much work it would become. I have been completely going around the clock on this one.

ConvergenceRI: It sounds like it turned into a much bigger task than you envisioned.

HAFNER: My initial thought was that we would do six-minute, little mini-episodes. But the women deserved more; they just deserved more than six minutes. The first one was 11 minutes, and the next one was 15 minutes, and then 16 minutes. And today’s [on Lilli Hornig] was 18 minutes.

It still doesn’t feel like it is enough. I wonder what my father would have said. I’m dying to know about the class he taught you.

ConvergencRI: I have a couple more questions to ask before I get to your father’s class on Oppenheimer. Were there any big surprises that you found in the research? It seemed the stories about the women involved with the Manhattan Project kept evolving.

HAFNER: Have you listened to the entire series?

ConvergenceRI: I have listened to the first three. I thought they were very good. What I sensed was that there wasn’t a lot of historical records to find about these women. Is that accurate?

HAFNER: Yes, it’s really too bad. It is really kind of a tragedy. There were these two women, Ruth Howes and Caroline Herzenberg, who decided to chronicle the lives of the women who worked on the Manhattan Project.

Ruth Howes was a physicist. She went and interviewed everyone she could find. And then, the women wrote this book, called Their Day in the Sun: Women of the Manhattan Project. I went to visit Howes in Santa Fe, New Mexico, about a year ago, and I interviewed her. During the course of the interview, I asked her: “Do you have the transcripts of your interviews?”

“I don’t think so,” she said. “I didn’t save them.”

“What do you mean, you didn’t save them?” I asked.

“I didn’t think anyone would care,” Howes said.

That is the book that everybody is now turning to, because it is the only record, in a lot of instances, of what these women did. Except for when they did their oral histories, like Lilli Hornig did, with the Atomic Heritage Foundation. But not many of them did.

We just got an email today saying, “My science teacher in high school told us she worked on the Manhattan Project.” Peggy Baird. And, I went and looked her up, and that must have been her married name, because there is no record of a “Peggy Baird.” It’s really sad.

[As an aside: “I am washing greens,” apologizing for the extra noise in the background.]

ConvergenceRI: That’s OK, You can multi-task. Your father’s class was fascinating.

HAFNER: Wait a second. Honey, you have to hear this, about my dad’s class [asking her husband, Bob Wachter, dean of Medicine at University of California at San Francisco, to join the interview].

I am asking my husband to listen. He never met my father, which is really sad.

[Introducing me] This is someone who took my father’s class on Oppenheimer as a freshman at Hampshire College. This is Bob.

WACHTER: Hello.

ConvergenceRI: Hi, Bob. The class attracted some of the best and the brightest of the scientific students who were in the first class at Hampshire. The level of dialogue was really high. I think that your father was a bit surprised. He was constantly being challenged about his presentation of the facts in class.

HAFNER: Really? Oh my God. It’s sounds just like my Dad. He would present stuff as if he was [the authority].

ConvergenceRI: The questions that got raised in class were really provocative. I remember there was one dialogue that occurred around, there was an old adage, your father had cited: “The more you know, the worse things get. And the worse things get, the more you know,” which he used to describe the Oppenheimer situation.

One of the students got up, went to the blackboard, and said: You can graph that as an inverse relationship between knowledge and ignorance.

And someone else in the class, jumped up and said, no. The graph should really be a… I forget the math term for it, but it’s where the lower end of the curve hits a nadar and then starts climbing back up, when the inner knowledge exceeds your outer knowledge. This was all happening on the blackboard, and your father was like, “Huh?”

All this occurred in five minutes during the class, talking about the lack of self-realization of Oppenheimer, and how he kept digging himself a bigger and bigger hole, about his interactions with people and whether they were communists. And, the fact that he kept lying.

HAFNER: He kept lying about what?

ConvergenceRI: His interactions with the women he was involved with, and his friends, and whether or not they were communists, and whether or not he had been approached to share information about the atomic bomb research with communists, and he was very vague about that. Did you read the book by Philip Stern?

HAFNER: I’m kicking myself, because it was on my dad’s bookshelf forever, and when he died, I didn’t take it, and I am just so angry at myself. He had so many books, I didn’t read.

ConvergenceRI: That was the text for the class. On Sunday afternoon, Hampshire students often played pick-up basketball at the Amherst Cage, and one of the professors who played in the game was Lester Mazor. He heard me talking about the class, and what I thought was missing, how as a scientist Oppenheimer was ill-prepared to deal with the legal way the case was being prosecuted. The lawyer representing Oppenheimer was totally outfoxed by the legal folks from the government. And so, the next day, Lester Mazor showed up in class.

Remember that this was 1970; it was a year before the Pentagon Papers were released, when the issue of government security would become front-and-center again. It was an amazing level of inquiry for a college freshman science class.

In many ways, the case against Oppenheimer boiled down to the personal animus of one man, Lewis Strauss, who was then chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, who felt he had been humiliated by Oppenheimer and, through the security hearing, now sought, in turn, to humiliate Oppenheimer.

The irony was that all the government had to do was to let the contract with Oppenheimer expire, which would have occurred a few days after the verdict that Oppenheimer was a security risk was announced.

Getting back to your podcast, what was your own learning curve in the process of giving voice to the forgotten women of science? How was it a learning experience for you?

HAFNER: When we started working on “The Lost Women of Science” project, we had no clue that there would be so many stories to tell. In fact, the guy at the Sloan Foundation said to me: “Well, this will be a short-lived project.”

ConvergenceRI: [laughter]

HAFNER: I had a feeling he was wrong, but I had no idea how wrong he was. I mean, it’s amazing how many women there are who did incredible things, The tragedy of all this stuff getting lost is just the worst part of it. Nothing got saved, unless someone was smart and saved the papers.

That’s the big thing, the biggest kind of shocker to me, was that these women were so unappreciated. And often, they also had a lack of self-appreciation. They often ended up totally disappearing in history.

ConvergenceRI: That must resonate with your own story of lost papers and trying to resurrect things about your father. [pause] A lot has been made about the juxtaposition of the movies, “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer.” I think it is a strange relationship in the way we get information which is often from the unhistorical tracks from the movies, rather than from other sources. The gaps in the histories are quite profound. But what do you think?

HAFNER: I have to say, that’s so true. My dad, there are so many things that he was interested in that I didn’t pay attention to when I was young. If only I had.

I’m thinking about his papers. My sister and I, we had kind of a tough time when my dad died, I wanted to take a lot of his papers, just to have them. I bet the syllabus and a lot of notes from the Oppenheimer course would have been in his files. He kept everything. And she just wouldn’t let me take anything.

And then, she died. And her husband has everything of my father’s. This is making me so sad. I never talked about it, but he did have a way of kind of lecturing at you, if you know what I mean.

ConvergenceRI: Yes.

HAFNER: And, he didn’t really listen that well. And, I bet those students really surprised him.

ConvergenceRI: I think that is what happened in this class. I think he was used to being in charge of the way that knowledge was dispensed. And, I think he had to find new, different ways of listening. A legal expert would come in and talk about the Oppenheimer case, not because of security concerns, but because of what went wrong legally, a different way of approaching the story.

HAFNER: He was a physicist. Did my father bring the physics into it?

ConvergenceRI: Yes, he attempted to. There was someone who waa involved with the Manhattan Project, who talked to us for one class. He turned up in the Philip Stern book; he was teaching at UMass. What was remarkable was the level of inquiry that was happening at Hampshire. Where else, 50 years ago, was anyone talking about Oppenheimer?

HAFNER: Exactly. Do you think that you were lucky to have a front-row seat to that level of inquiry?

ConvergenceRI: Absolutely. A lot of things didn’t work at Hampshire College in the first few years of the school. What did work was that you learned that if someone told you no, it wasn’t a final answer. You had to go out and figure out a way of not getting stuck. Many of the things in my life have involved learning how “not to get stuck.” Figuring out what you had to do, despite what the bureaucracy said. That type of inquiry and the ability to ask good questions, and to listen, are sort of how I evolved in my career as a journalist.

Clearly, the women involved with the Manhattan Project and the lost women of science were challenging the boundaries of what was expected between men and women and the roles that they should play. Do you have any reflections on how difficult it was for the women to challenge those boundaries?

HAFNER: Oh, absolutely. I mean, they did it all the time. Some of them did it more vocally than others. Like in the podcast from today, Lilli Hornig followed her husband to Los Alamos. And, I love the line, “I don’t type. I never learned how to type, in graduate school at Harvard. They didn’t teach typing.”

So many of the women we talk about, in The Lost Women of Science, were in exactly that position. That if “x” hadn’t happened, if there hadn’t been for “x,” they would have just ended up having babies. And then, the women had to choose, between having babies and doing their science. Like, when does a man ever have to choose?

ConvergenceRI: What are you going to do next?

HAFNER: I’m still going forward with “The Lost Women of Science.” We have a bunch more coming out.

But I’m writing another novel. I’d love to say I’m in the middle of it; I’ve got the contract. And I have been paid the advance, but I have not actually been able to focus on it because of this damn podcast.

My whole family is on my case to not work so hard. When you and I were talking about setting up a time to talk, and I said that I was drowning, I was not kidding. I woke up the other night and I was completely convinced I was having a heart attack.

ConvergenceRI: What do you do to relax?

HAFNER: I play tennis and golf. ...I should probably ring off.