What does a doctor say to parents of a toddler who has been found with elevated levels of lead?

The damage done

As Dr. Simon so poignantly writes about, the heart-breaking reality of lead poisoning requires more than effective laws for screening, for follow-up with a caring pediatrician, for education of parents, and for studies that document the pernicious way that elevated levels of lead in a child’s blood impact their reading readiness.

As a result, Fine changed the state’s public health priorities, and built a coalition of advocates within state government – including the state police – to address the issue.

[Editor’s Note: The annual toll of overdose deaths has more than doubled, to 435 in 2021, and the nature of the epidemic has shifted, from prescription painkillers to heroin to fentanyl.]

The high medical and economic cost of gun violence has begun to be documented in a new series in the Providence Journal. Why not a similar series on lead that makes the economic externalities part of the equation?

Consider inviting Susan Orban, coordinator of the Washington County Coalition for Children, as a guest. She will be leading a forum on Wednesday Feb. 8, to talk about the state of emergency for Rhode Island’s youth mental health.

The statistics in the news release promoting Orban’s forum are sobering: Nearly one in five [19 percent] of Rhode Island children aged 6-17 have a diagnosable mental health problem. One in 10 has a significant functional impairment. And, every year, one in 10 Rhode Island high school students report that they have attempted suicide.

Rhode Island Kids Count released a policy brief last week detailing the “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Maternal, Infant, and Young Children’s Health in Rhode Island.” But the racial and ethnic disparities will not change until our point of care structure does, according to one pediatrician. There are approximately 22,751 kids living in Pawtucket and Central Falls, according to Census data. How many pediatricians are in private practice in those cities? How many children rely on the community health centers for their care?

Editor’s Note: Ten years ago, in 2013, Dr. Peter Simon, now retired, wrote this column for ConvergenceRI. He had initially been denied permission to publish it by the Governor’s office. Given the failure by the R.I. General Assembly to pass legislation to replace lead water pipes in the state, it seemed appropriate to republish the story., in a belated celebration of Groundhog Day.

The conversation that Dr. Peter Simon recounted, with parents of a child newly diagnosed with lead poisoning, is a conversation that is still occurring all across Rhode Island, despite the best interventions by municipalities such as Central Falls to enforce the building codes protecting children and families, and the aggressive legal strategies pursued by R.I. Attorney General Peter Neronha to hold negligent landlords accountable for their failures.

On Jan. 31, the Attorney General announced lead remediation agreements totaling more than $700,000, against the owners of four lead-contaminated properties in Providence and Burrillville. “Instances of lead poisoning in children throughout Rhode Island are absolutely preventable and in these cases, are the consequences of landlords violating clear public safety laws,” Neronha said.

R.I. Senate President Dominick Ruggerio told WPRI that replacing 35,000 lead water pipes is one of his top priorities. The state is slated to receive $141 million from the federal bipartisan infrastructure law, but the total cost could be as much as $225 million to do so, according to reporting by WPRI

In January, Ruggerio introduced legislation that would require all lead water pipes to be replaced over the next 10 years. A similar bill co-sponsored by Ruggerio in 2022 was approved by the Senate but not by the House.

PROVIDENCE, May 15, 2013 – Last night, as has been my pattern since leaving my private practice to join the R.I. Department of Health in 1984, I went to the Providence Community Health Centers' Central Health Center on Cranston Street, in the West End of Providence, to see patients alongside Dr. Ellen Gurney and the rest of the Pediatric Team there.

Ellen has been a terrific partner for me, not only watching over my care of her practice’s patients and families, but as an instigator of my thinking about many maternal and child health initiatives over the years, most notably the Early Childhood Task Force in Providence in 1999.

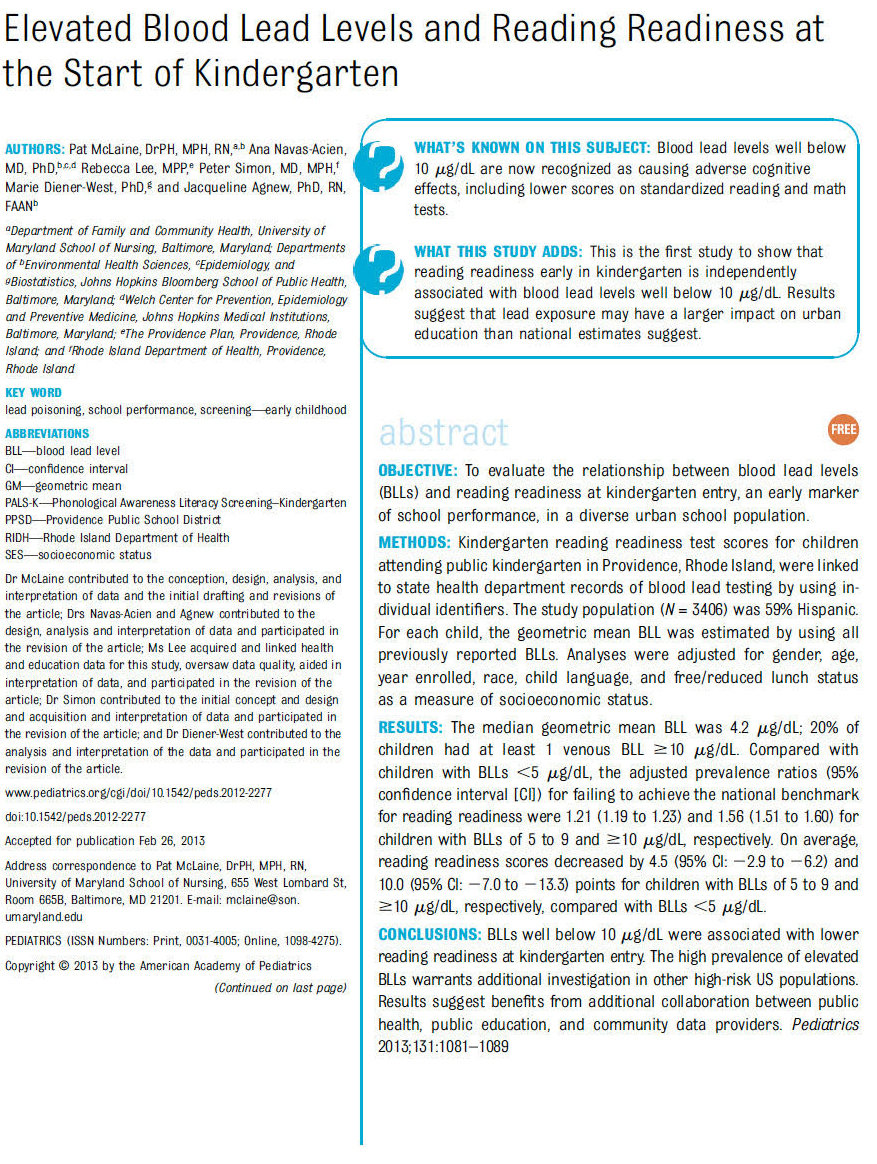

On the Monday preceding this clinic, research coming out of the Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health, conducted in collaboration with the R.I. Department of Health, the Providence Plan and the Providence Public Schools, was published by Pediatrics, the journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. [The study found that lead exposure contributed to decreased reading readiness at kindergarten entry.]

This research was the culmination of a local and national effort to advocate for what is called “healthy housing” to address social and environmental conditions that contribute to the disparities in health and education threatening the sustainability of our community.

The findings of the study led by Patricia McLaine, Ph.D., showed that blood lead levels as low as 2 micrograms per deciliter in children had a negative impact on measures of kindergarten readiness in a well-controlled regression model.

So, when Ellen asked me to see one of her patients and his parents about a recent blood lead test result of 5 micrograms per deciliter [the current standard of lead poisoning in children by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention], I could tell she was doing it again – giving me a nudge towards an issue of hers that needed my thought and action.

So, feeling at the top of my game, I went in, followed by one of the pediatric nurses who usually was delegated the task of discussing blood lead results with parents.

In the examination room with his parents was a handsome 22-month-old little boy who was busy exploring the exam table, using lots of language that his mom clearly understood, but that challenged the rest of us, including dad, to understand.

As I usually do, I asked dad and mom why they had come that evening. They told me they had received a letter from the R.I. Department of Health telling them that their child’s blood test had shown an elevated level of lead, and that they should make an appointment with their primary care provider to discuss next steps.

I skipped over the fact that the letter was signed by yours truly and went directly to the facts about what a result of 5 micrograms per deciliter means.

With every skill I possess in health communication, I walked a tight rope, trying to balance the responsibility to fully disclose the nature of all the effects of lead on a child’s brain while at the same time knowing how limited I was in predicting the outcomes for one child.

My goal was to help these parents protect their child’s brain and, at the same time, help maintain their self-confidence. I was trained to worry about the risk of creating a “vulnerable child.”

I pointed out the healthy nature of their child’s present behavior and development that we all could see from the small sample of time we were together, watching the toddler explore the room, engaging in a social interaction with the pediatric nurse who he had approached immediately when she entered.

I tried to emphasize what kind of experiences could enrich the child’s brain development and found myself recommending the things I have always done for every child and family over the last 35 years.

Talk, sing and read to your child; take them places like parks, grocery shopping, to the library. Play games with them and show them the things that you love to do. Learn as much as you can about what to expect from them at each stage of growth so that you do not interfere with their trying new things. Insert yourself when necessary to protect them from the hazards you can see that they cannot. Be ready to let them go to reach the goals we all want for our children: independence, self-direction and activation.

I then described ways to reduce exposure to lead-contaminated dust and dirt by wet mopping and wiping surfaces of toys and any other objects that toddlers mouth as a routine, recommended some nutritional guidance, and offered to prescribe some vitamin and iron supplementation to be added to his orange juice at breakfast, and scheduled another lead test for a month later.

The parents had no questions, so I said good-bye. I will not be seeing them again, so it won’t be possible for me to answer the questions that sit burning in my mind: how will this youngster do when he goes to kindergarten. Will he succeed in his educational career? Will his lead exposure be overcome? Will his teachers know how to help him learn to read?

Dr. Peter Simon, now retired, was the medical director of the Division of Community, Family Health, and Equity at the R.I. Department of Health when he wrote this story for ConvergenceRI. He had been recognized as a national Public Health Hero in 2012, and he received a 2013 Community Hero Award from the Childhood Lead Action Project.