What it means to be a barometer of truth

An in-depth interview with OHIC’s Cory King, as part of ConvergenceRI’s continuing coverage of the financial structure and performance of RI’s hospitals and health systems

In Massachusetts, as detailed by ConvergenceRI in the recent story, ”What is public health in 2024?” Optum, the for-profit division of UnitedHealthcare, is in line to purchase the physician practices of the financially troubled Steward Health Care, making it one of the largest owners of physician practices in both Massachusetts and the nation.

One of the more perplexing questions surrounding health care is the failure of the Rhode Island news media to do a better, more comprehensive job in covering the largest private employer in the state.

PROVIDENCE – It is two weeks since the Rhode Island Foundation released its study of health care costs conducted by Manatt. But, after the initial burst of interest from news media in Rhode Island, the conversations around the high costs of health care delivery and the unsustainable enterprise of health systems and hospitals have returned to the shadows, lurking in the darkness as the major cause of the state’s ongoing economic troubles.

People do not seem to read anymore. Perhaps they are put off by the sources of information that always seem slanted and filled with false, alluring promises, much like the come-ons at the bottom of news stories found online following any TV or newspaper story. “Eat this vitamin for sciatic nerve relief,” or “Lose up to 7 pounds your first 7 days,” or “Red flag signs of leukemia most people may not be aware of.”

Patients, much like customers, have been left to fend for themselves to find meaningful answers to their questions and concerns amid an avalanche of false advertising.

Last week, ConvergenceRI was called “a barometer of truth” by one of the top communications officials for a health care enterprise in Rhode Island. A top leader of a government agency bestowed another compliment on ConvergenceRI: “You ask very good questions.’ In a time of great misinformation and disinformation, ConvergenceRI can only respond with a heart-felt, “Thank you!”

If you read last week’s in-depth coverage of the initial release of the Rhode Island Foundation study, in a story entitled, “Show me the data – and the money!” it promised continued coverage of the study, “Financial Structure and Performance of Rhode Island’s Hospitals and Health Systems Study.” [See link to the ConvergenceRI story below.]

Here is the first of what will become several follow-up stories, an interview with Cory King, now the permanent head of the R.I. Office of the Health Insurance Commissioner. The story may lack the kind of click-bait that Rhode Islanders may have become accustomed to in their news coverage, where anxiety, outrage, and mayhem capture and exploit their worst fears, but it does provide solid ground to understand what the study said, what salient topics were missing from it, and the distance still needed to travel to ensure that Rhode Islanders can have access to a health system that is predicated on improving their health, not the bottom line of the corporations involved.

As Cory King defined public health in Rhode Island, “The health of an individual or community is more than the health care consumed by that community. Public health,”’ he continued, “is a set of public interest outcomes that can only be advanced, or maximized, through an interdisciplinary approach.”

ConvergenceRI: The study seemed to leave whole areas of cost analysis unexamined, such as pharmacy costs. Is that an accurate conversation?

KING: First, I think the Rhode Island Foundation deserves a lot of credit for pulling this off. Managing hospital and health plan funders with disparate interests must have been a challenge. The title of the report, ‘Examining the Financial Structure and Performance of Rhode Island’s Acute Hospitals and Health Systems,’ appropriately conveys the scope.

There are significant components of total medical expense and service delivery that are not covered in the report. But the Rhode Island Foundation was careful not to duplicate work that is going on elsewhere in the state. As you are aware, OHIC measures total health care spending in the state and reports on cost drivers each year.

We also publish reports throughout the year on special topics. This is like the work that is done by the Massachusetts Center for Health Information and Analysis and the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission.

OHIC’s next report, Health Care Spending and Quality in Rhode Island, will be published on May 13. This year, we are adding a chart pack that will include deep dives into hospital inpatient, hospital outpatient, and professional physician spending, looking at changes in spending per person, utilization, and payment per unit.

The Cost Trends Steering Committee also recently adopted a set of public health and health equity measures, and we will publish baseline performance data on those measures.

We also have some analyses on inpatient care migration to other states, outpatient chemotherapy migration, and trends in emergency department use and severity to be published soon. These are just some of the factors that impact how much Rhode Islanders pay for health care.

ConvergenceRI: The breakdown of costs did not get into the difficulties of patients gaining access to primary care providers, and what those delays in care cost the system. Is that an accurate observation?

KING: Correct, the study did not examine access to services, such as primary or specialty care. In fact, the study steered clear of any consumer-focused analyses.

Measures of access to care, affordability, or patient experience of care could be added in the future. I do not think this is a fault of Rhode Island Foundation report.

The study, which is quite extensive in its coverage of a more limited topic, comprises more than 100 pages, and I applaud the Foundation and Manatt for getting it done with such a high degree of professionalism and fairness to the topic.

I do believe that legislators and other audiences who are not steeped in health care finance and policy will have a hard time interpreting the report. This creates a risk that certain industry players will utilize bits and pieces of the report to advance their own self-interests.

To truly assess affordability and other consumer-focused measures of how our health care system performs will require a different approach and some separation from the vested interests of hospitals and insurers. Addressing affordability for the consumer is the role of public policy because health care markets have a poor track record when it comes to producing affordable health care and affordable health insurance.

ConvergenceRI: The study seemed to be focused on hospital systems, and not other kinds of care delivery. For instance, the non-hospital centric OrthoRI has developed an alternative vision.

KING: The focus was limited to hospitals and hospital-based health systems with some metrics on premiums, utilization, median household income, and workforce across the three states of interest.

The core focus was financial performance, with a combination of metrics on reimbursement rates, operating costs, and operating margins from public data sets. None of the reimbursement or cost analyses focused on physician reimbursement or practice expenses because these were out of scope.

Collectively, hospital inpatient and hospital outpatient services account for approximately 43 percent of commercial total medical expense, net of pharmacy rebates. This proportion differs for Medicare and Medicaid.

I think the report lays the groundwork for future analyses, but it is no substitute for the type of analysis that should be produced by government. I would like to see a deeper dive into hospital operating margins by payer type [commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare], an analysis of hospital-reported Medicaid losses and community benefits, and a broader assessment of the drivers of hospital and health system operating margins.

Through OHIC, the Cost Trends Steering Committee, and the Health Spending Accountability and Transparency Program, policymakers now have insights into how Rhode Islanders spend their health care dollars.

Health care spending is provider revenue and I think the state would be wise to consider investing in a program, like the OHIC program, that has the assessment of provider financial performance and operating costs as its core focus.

The OHIC focus on spending and quality and a program elsewhere focused on provider finances and operating costs would complement each other very well.

ConvergenceRI: The connection between health equity disparities and the cost of care did not seem to be explored; is that an accurate observation?

KING: Correct. The interaction of health system finance with health equity was not part of the scope but could be part of a future iteration of the report.

ConvergenceRI: How would you evaluate the value of the study moving forward, in parallel with the tasks ahead for OHIC?

KING: Thank you for asking this question. I think interested parties will use this study for different purposes.

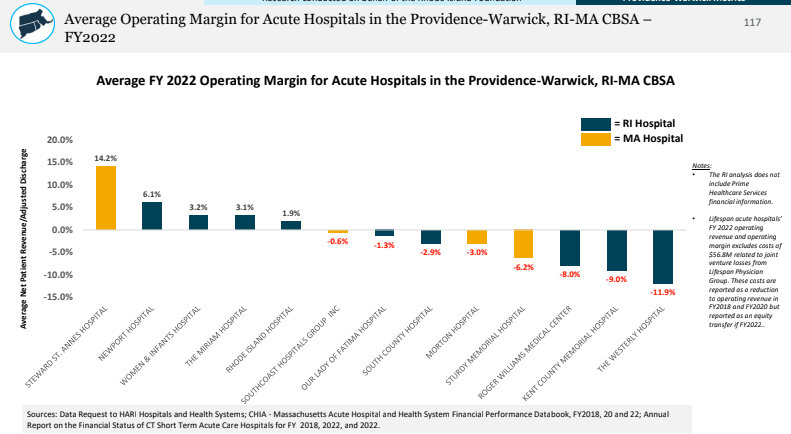

From my perspective, the most interesting data are the graphs included as Appendix A. Where the Rhode Island Foundation and Manatt really excelled was taking a granular geographic approach to the analysis of hospital reimbursement and operating costs.

The Providence-Warwick core-based statistical area, which includes parts of Massachusetts. is a good proxy for the hospital market. Pages 110 – 117 show that many Rhode Island hospitals are reimbursed consistent with, if not better than, Massachusetts’ hospitals just across the border.

The same is true of revenue per adjusted discharge and operating costs. Geography really matters. Providence is not Boston. Wakefield is not New Haven.

Where I plan to use the study is to focus on variation in reimbursement among hospitals within Rhode Island.

A few years ago, OHIC mandated that commercial insurers increase their inpatient reimbursement for hospitals that were paid below the Rhode Island network median at the insurer level.

This provided a boost in reimbursement for hospitals like Landmark, Our Lady of Fatima, and Roger Williams Medical Center. I believe OHIC has an opportunity to think about ways to use its regulatory levers to make strategic investments in our lower- reimbursed, high government payer mix hospitals that will be affordable for employers and working Rhode Islanders and will support these important community assets.

Finally, as people review the report, they should keep in mind that there have been significant changes in state and federal payment policy since the period of time covered by the report.

For example, at the federal level, in 2021 Congress reinstated the imputed rural floor. This reversed a policy change made by the Trump administration that essentially cut Medicare reimbursement for hospitals in states that do not have a rural hospital.

More recently, Gov. McKee worked with the hospital industry to modify the provider tax and secure federal approval for a new state directed payment program that boosts Medicaid funding to hospitals by approximately $110 million per year.

This helps maximize Medicaid funding and will improve hospital financial performance. I don’t think the state’s recent investments in provider capacity through Medicaid, including the Medicaid state-directed payment program for hospitals, have gotten enough attention.

ConvergenceRI: The study did not seem to address the peril and risk of for-profit private equity investments in hospitals. Is that a major missing component?

KING: Correct, private equity ownership was not a focus of the report, but significant work has occurred on this topic elsewhere. The Attorney General has done an exemplary job uncovering the significant downsides of private equity ownership in his oversight of the Prospect Medical Holdings hospital conversion a few years ago and applying meaningful conditions of approval to that transaction.

I don’t think the Foundation’s report needed to cover this ground. However, you raise a broader set of policy questions. What role, if any, should private equity play in ownership of health care resources, such as hospitals, nursing homes, or physician practices? What are the risks? How can those risks be mitigated or solved-for through regulatory oversight? And how do you manage the stakes of a transaction for health care resources that local communities need, such as hospitals or nursing homes, if private equity is the only potential buyer?

ConvergenceRI: In my most recent edition of ConvergenceRI, I reported in great detail about the problems with Optum controlling some 95 percent of behavioral health care management for Medicaid managed care providers. What are the cost metrics needed to further this discussion?

KING: Your observation about the dominate market presence of health care purchasers raises a different set of questions. A lot of research has focused on the impact of consolidation of providers and the impact on prices and health care spending. However, market structure and consolidation on the purchaser side matters as well.

ConvergenceRI: What questions haven’t I asked, should I have asked, that you would like to talk about?

KING: You have asked some very cogent questions. I suppose one question that I would have liked to be asked is: “Did anything in the report surprise you?”

There were some small things that surprised me:

- Rhode Island has more emergency medicine physicians per capita than CT or MA.

- Rhode Island has more registered nurses per capita than CT.

- Hospital operating losses in 2022 were greater in CT and MA where health care is more expensive, than in RI.

But overall, I was not surprised by much of the report. Rhode Island has done a better job than Connecticut and Massachusetts controlling rising health care spending. This has saved employers and working Rhode Islanders money that can be committed to other needs, like housing, childcare, and transportation.

I also wasn’t surprised that there are differences in workforce density or average salaries across states. The cost of living varies from state to state as do other economic factors. If we did a report that analyzed other professions, it wouldn’t surprise me to see variation in the density or average earnings of plumbers, electricians, hospitality workers, truck drivers, teachers, firefighters, etc., across states.

ConvergenceRI: Bonus question. What is public health?

KING: In my view public health is set of public interest outcomes that can only be advanced, or maximized, through an interdisciplinary approach. The health of an individual or community is more than the health care consumed by that community.