A New Year resolution for Rhode Island primary care professionals

Dr. John Wasson proposes a different way to use technology to build a better relationship with patients and stop schlepping the sludge

HANOVER, N.H. – A recent analysis of the data released by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid from the second year of quality performance from its 333 Medicare Shared Savings Programs Accountable Care Organizations found three somewhat surprising outcomes.

The analysis, published in Dec. 21 issue of Health Affairs Blog, reported that the majority of the pilot ACOs, 241 out of 333, or 72 percent, did not generate any savings.

Second, the analysis found the two groups – those that produced savings and those that did not – “spent virtually an identical amount per member,” with savings determined by the level where the baseline benchmark had been set.

Third, one other factor statistically associated with savings was the patients’ rating of their doctor.

There is another way to interpret what the numbers and the analysis showed.

First, that if three-quarters of the pilot ACOs did not achieve savings, the experiment may have proven that the ACOs as currently constructed do not work very well.

Second, if the savings achieved are based upon the arbitrary level where the baseline benchmark, and the practices are spending virtually the identical amount per member, the savings are also arbitrary.

If the savings are arbitrary, and if the practices are spending the exact same amount per member, then the patients’ rating for the doctors and its relationship to spending may be a red herring, an artifact of the way the analysts chose to slice the data.

A more revealing kind of analysis and metric would be to put the focus on the patient’s own confidence in making decisions in managing his or her own health – a different kind of metric, producing better outcomes and more consistent savings. Here’s a New Year’s resolution for how Rhode Island primary care physicians can achieve that.

Is measurement our drug?

Front-line doctors have a pyramid on their backs; let’s euphemistically call it a pyramid of accountability. Near the top are the so-called certifying organizations. Two well-publicized examples just extracted about $100 million between them.

The professional medical organizations and government-affiliated regulators, too numerous to count, are also mining their share.

Next comes the measurement industry. A recent Institute of Medicine study reported that the 850 integrated health systems in the U.S. spend between $3.5 and $12 million each for measurement. [Wasson, Annals of Family Medicine, 2015]

Measurement is our drug, according Liz Ryan, writing in Forbes in 2014. We measure everything in business to prove to someone who’s not in the room that we did what they told us to do, she wrote.

For most front-line doctors, the current quality measures are both overly process-oriented and too numerous. In addition, they may not track well to health outcomes, and they create a significant burden for providers, according to what Mark Miller, the executive director of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, or MedPAC, wrote in 2014.

Choosing a different approach

In contrast to an ophthalmologist who performs predictable steps to remove a cataract and replace it with an intraocular lens, primary care physicians, or PCPs, must deal with any need that might walk in the door.

Too often techniques to measure and improve the care by specialists have been aggregated and layered on primary care practices where, almost invariably, they prove burdensome and inappropriate.

As a result, the tired wheeze that “if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it” has created a big, expensive problem for primary care practices that can spend countless dollars and hours schlepping measurement sludge.

Nevertheless, there are two reasons for optimism about an emerging future of care improvement for primary care.

First, communication tools now can help patients articulate and share their needs with clinicians in an actionable form – and, at the same time, automatically generate measures to catalyze better care.

Second, these tools are inexpensive and easy to implement. Moreover, patient completion rates for HowsYourHealth.org and other such tools are high because patients and practices perceive immediate benefits.

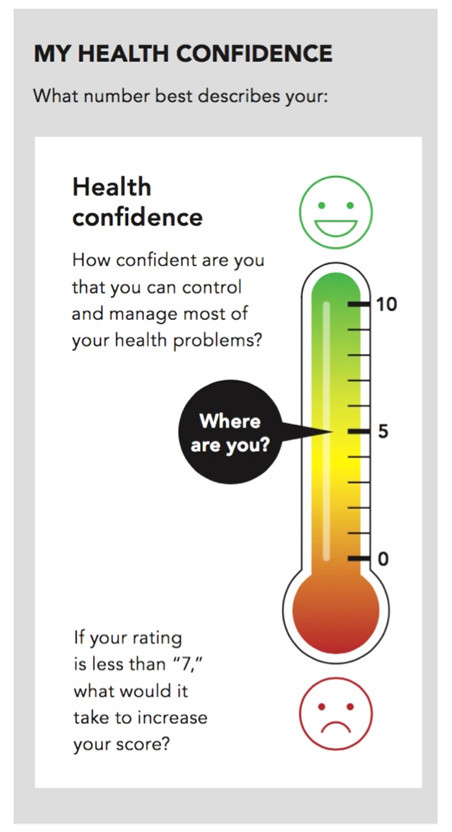

As a bare-bones example, the results were very positive when a Vermont primary care practice decided to use a Health Confidence tool [see illustration] to “get on the same page” with its patients.

Why? The tool offered more than a number on a thermometer. It contained an explicit action for both the patient and the health professional. In other words, both partners were led to ask: “What can we do to make health confidence better?”

Easy to assemble, use

Behaviorally sophisticated, web-based assemblages of similar tools are inexpensive and easy to implement. These web tools also foster engagement between patients and primary care providers, enabling them to align their interests for research and development of better care.

A New Hampshire practice, as an example, routinely places the results on HowsYourHealth.org on its website and explains the improvements it is planning. [See link below.]

Not to be outdone by neighbors in Vermont and New Hampshire, a Rhode Island PCP, Dr. Lynn Ho, has been using this low-cost, easy to use, high-yield technology to leverage patient engagement levels in the practice over time. [See link below]

Changing the way it is done

The results are impressive: patients are being served, patients and health professionals are engaged in a partnership, money is being saved, there is less sludge to schlep, and practices – and the relationship between doctors and patients – are being improved.

Why aren’t these tools already at the core of all primary care?

One explanation is that the 20th century ways of providing and regulating care are still the way “it is done.” Change is slow. And, when financial incentives and committed infrastructure under gird the status-quo business models, change is particularly difficult.

Another explanation is more pernicious.

During the last two decades of the 20th century, PCPs, using the most rigorous study design, the randomized controlled trial, addressed broadly relevant topics such as provider continuity, telephone house calls, the use of communication technologies, and the value of patient engagement for management of chronic conditions.

Since then, sadly, top-down imposition of innumerable, largely untested methods and measures for quality and cost control have flourished – and resulted in the stifling of PCP-initiated inquiry.

As one example, top-heavy maintenance of certification [MOC] has become so onerous that PCPs have had to resort to revolt to receive a temporary reprieve. But demanding reprieves and being asked to “sit at the table” as additional policies and procedures are proposed for them are not useful methods to foster PCPs to be scientists.

Most PCPs want and need to have tools that actually generate research and development within their own practices to make primary care efficient, effective and enjoyable.

The opportunity

Fortunately, web-based communication tools offer an unprecedented opportunity to quickly address and answer questions that matter to patients, PCPs and policymakers.

Instead of being piece-workers in a large industrial factory, PCPs now have the tools to reassert themselves individually or in groups, addressing scientific questions, including:

• How can patients best be invited and engaged to assist an overworked practice in taking advantage of these new communication tools?

• How will simple queries of patients compare to the complex questions already in use?

• What do patients across Rhode Island feel about a new preventive method? How do their responses differ by age, gender, financial status and co-morbidity? What modification would they suggest instead?

• Which PCPs in Rhode Island are attaining exemplary results for comparable patients? What are they doing that can be translated to other PCPs?

• What has been the impact over time of the translation of the methods of the exemplary PCPs to others?

• Which is more cost effective [in terms of reducing utilization and improving patient health confidence]: to be exposed to the low-cost technology whereby all with low confidence will be provided low-cost, stepped intervention vs. the currently popular high-cost interventions targeted at high-cost outlier patients?

• Which is more cost effective [in terms of producing improved patient assessment of improved care quality and health confidence]: to report NCQA process measures for the “medical home” or to be exposed to the low-cost communication technology?

With the phrase “the medium is the message,” Marshall McLuhan argued that technologies are the messages themselves and not just the medium.

Almost 50 years later, communication technologies are transmuting simple measures into behaviorally sophisticated information for meaningful engagement between patients and PCPs.

Moreover, these technologies can now expand PCPs’ opportunities to again become rigorous scientists in a quest to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of health care.

Because of Rhode Island’s size and its health service collegiality, its PCPs are in a very strong position to demonstrate the value of this New Year’s technological resolution.

Dr. John Wasson is an emeritus professor at Dartmouth Medical School. He recently addressed the quarterly meeting of the R.I. Care Transformation Collaborative. [See link to ConvergenceRI story below.] This story is a response to a request by ConvergenceRI for him to write a story about how tools such as HowsYourHealth.org could be applied in Rhode Island.

Wasson discloses that he, under license with the trustees of Dartmouth College, makes the HowsYourHealth.org, HealthConfidence.org, and MedicareHealthAssess.org tools described in this article available for free.