A plan to take action, as thousands of lives hang in the balance

New plan to address addiction and overdose deaths in Rhode Island recommends a strategic path to move from crisis intervention to public health best practices, but how resources will be invested remains unknown critical factor

“Equally important is focusing on the person’s academic, social and vocational goals,” Heinssen said in the interview. “An intervention called ‘Supported Employment, Supported Education’ is something that plays a key role in this treatment, because it takes into account the fact that most of these young individuals want to return to school, they want to become productive members of the workforce, and it offers a very active intervention to get them at the places that they most desire, and then offer support to them in those environments until they get their feet on the ground and are feeling confident, and then [the effects of schizophrenia begin] to recede into the background.”

More than just taking a pill to combat the disease of addiction, which is often catalyzed by taking prescription drugs for pain, the new research on effective treatments for schizophrenia appears to offer insights into best practices on how to treat such brain disorders.

PROVIDENCE – A draft of the strategic plan to address addiction and overdose in Rhode Island has been circulated to members of the Task Force on Overdose Prevention and Intervention with the somewhat amazing direction: “Please distribute the plan to any stakeholders,” asking for their feedback.

At a time when access to information in a timely fashion from Gov. Gina Raimondo and her administration has been called into question by an often frustrated news media, who feel that they have been consistently stonewalled, the task force leaders [and its co-chairs, Dr. Nicole Alexander-Scott, director of the R.I. Department of Health, and Maria Montanaro, director of the R.I. Department of Behavioral Healthare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals], have taken a different tack: broadly seeking public input on the plan, including setting up an online survey to gauge the public’s response.

[As such, a copy of the draft strategic plan made its way to ConvergenceRI, considered by some folks to be a stakeholder in the process; the newsletter is following the instructions, providing feedback.]

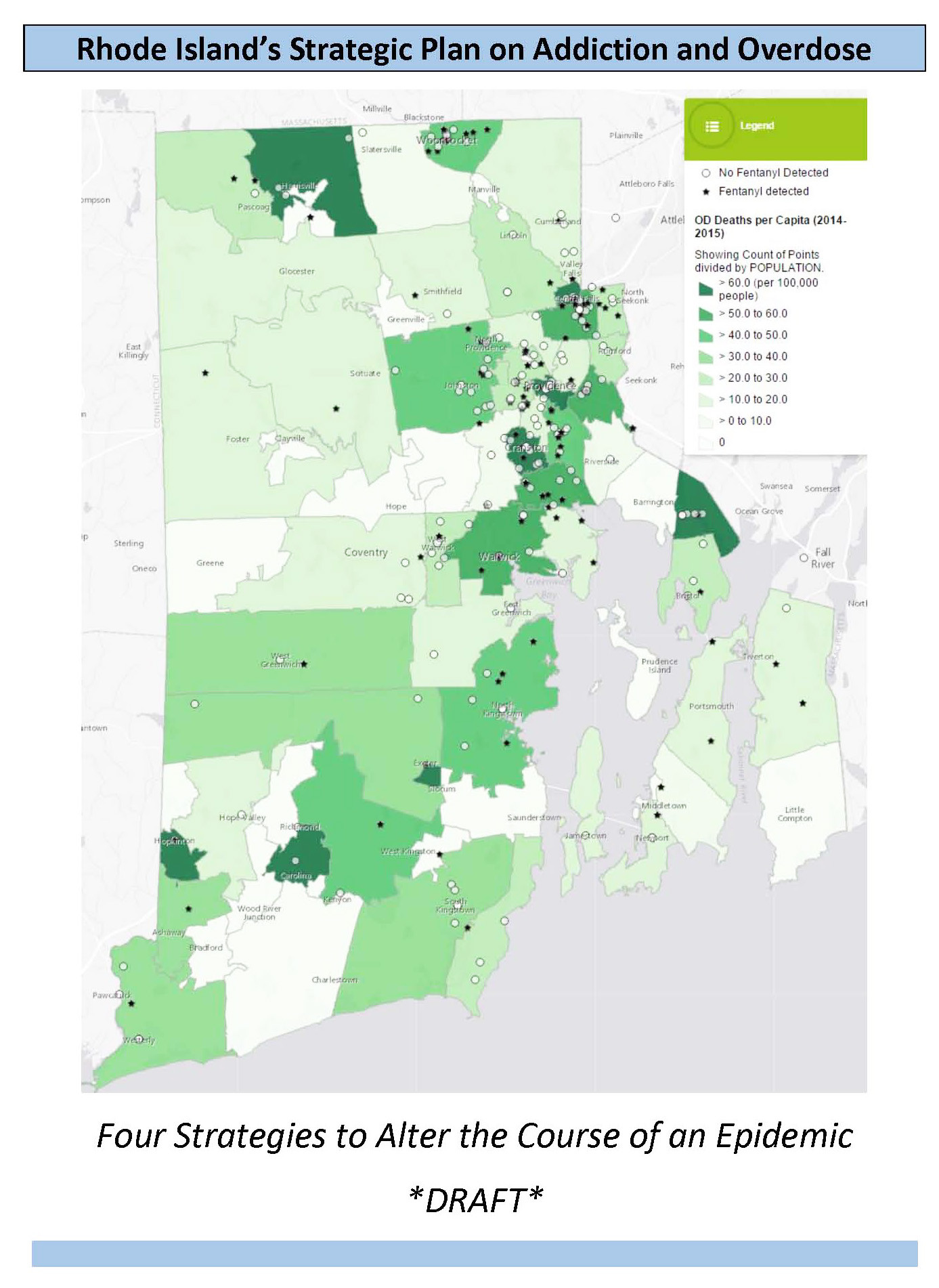

The dense, 15-page strategic plan, entitled “Rhode Island’s Plan on Addiction and Overdose: Four Strategies To Alter the Course of an Epidemic,” lays out a comprehensive approach, with the goal to “reduce opioid deaths by one-third within three years.”

Translated, that means reducing the number of overdose deaths in Rhode Island from 239 in 2014 to about 160 in 2018.

To put that into context, the R.I. Department of Health released data last week showing that through Oct. 21, the total number of confirmed drug overdose deaths that occurred in 2015 was 145.

But that number is expected to climb higher, when the data is adjusted for the last three months, given the agency’s caveat that “tests to confirm drug overdose deaths can take two or three months to be completed.” For that reason, the agency noted, the number of confirmed drug overdose deaths in August, September and October “were significantly lower” than other months in 2015.

Translated even further, the number of confirmed drug overdose deaths in 2015 appears to be on track to match the 2014 death toll. The new strategic approach is a timely effort to move from urgent crisis intervention to best public health practices.

The plan details an approach directed at treatment, reversal, prevention, and recovery, with specific metrics to measure the success of each part of the strategy. Even more amazing, in terms of public outreach, the strategic plan calls for the creation of a dashboard, an online “indicator panel” of relevant data to provide a snapshot of problems and progress, “including the key metrics across all four critical [strategy] initiatives.”

The recommendation is to create a public-facing dashboard and a password-protected dashboard, in order “to keep the public informed about progress and key stakeholders up-to-date with real-time data,” while preserving the privacy of patients.

The draft strategic plan will be discussed at the Task Force’s second public community forum to be held on Monday, Oct. 26, at the Buttonwoods Community Center in Warwick, from 7-8:30 p.m. The major focus of the meeting will be to discuss stigma in overdose and addiction, and how to address stigma in each of the major initiatives within the strategic plan.

Stigma is a very relevant topic when it comes to resources, too. As solid as the strategic plan may appear to be in its evidence-based, public health approach, the underlying issue is about resources and their deployment: how much money is the state actually willing to invest in saving the lives of Rhode Islanders? Is it as an important economic priority as, say, spending $5 million for consultants to design a campaign to promote tourism?

A larger, more fundamental philosophical divide, unresolved, is still at play here: is the scene of a drug overdose an emergency health episode, or a crime scene investigation? How quickly the R.I. General Assembly moves forward in reauthorizing the Good Samaritan Law will serve, as they say in the business world, as a leading indicator.

Framing the issues

Before taking a deeper dive into the draft strategic plan, it is important to set the stage by quoting, at length, the cogent, well-written preface, which no doubt will get lost in many of the other news stories about the strategic plan. The remarkable way in which the preface tells the story, frames the problem, and explains the approach is as important, in many ways, as the plan itself.

“Addiction and overdose are claiming lives, destroying families, and undermining the quality of life across Rhode Island. In 2014, 239 people in our state lost their lives to overdose, more than the number of homicides, motor vehicle accidents, and suicides combined. This is a ‘strategic’ plan whose goal is to complement existing overdose prevention efforts to achieve the most immediate impact on addiction and overdose. The plan is focused on four critical, strategic initiatives. It is not meant to be comprehensive, and by design, must be flexible to adapt to changes in this dynamic epidemic. As such, it proposes a publicly visible online ‘dashboard’ that will provide the public and policy makers with real time data to gauge progress on this epidemic.

“Opioid addiction [also called dependence] is a chronic brain disease that can develop with repeated daily exposure to opioids. There are strong genetic and situational factors that increase the risk of developing opioid dependence. Untreated, it is often eventually deadly. It is characterized by the development of tolerance [the need for an increasingly higher dose to achieve the same effect], and withdrawal [an extremely painful condition that occurs when people try to stop abruptly]. During withdrawal, people feel as if they will die if they do not get an opioid. The natural history of this disease leads to using greater amounts over time, which typically drives people to increasingly desperate and dangerous behaviors.

“For over a decade, opioid dependence and accidental drug overdose have been growing problems across the United States, and Rhode Island has been one of the hardest-hit. In 2013, Rhode Island had the highest rates of illicit drug use in the nation, as well as the highest rates of drug overdose in New England.

“This recent increase is directly related to a dramatic increase in the amount of opioids prescribed. The two main driving forces behind this increase were regulatory pressures encouraging more opioid prescribing and unscrupulous practices by some in the pharmaceutical industry.

“The result has been creation of a generation of people addicted to opioids. Many individuals begin with opioid pain medications – such as Vicodin, Percocet, or OxyContin – and, often for economic reasons, transition to heroin use, and injection drug use.

“Since 2002, rates of heroin addiction have doubled and heroin-related overdose deaths have nearly quadrupled. Adding to these challenges, benzodiazepines have become increasingly available, and overdoses related to fentanyl-laced illicit drugs have increased dramatically.

“This is a dynamic epidemic, exposing the need for collaborations between public health and behavioral health, reaching into the medical and pharmacy communities, and in partnership with public safety, representing a communal call for action.

“The major investment in battling the opioid epidemic, and drug use in general, has been through the criminal justice system. This has resulted in the highest incarceration rates in the world and is generally considered ineffective at reducing drug use, with high rates of relapse to drug use, crime and re-incarceration.

“Taking a purely punitive approach in the face of the current crisis is misguided and risks further harm to individuals and communities already struggling with addiction. Treatment with evidence-based medical therapies for opioid dependence has the potential to have a much more beneficial effect.

“It would seem appropriate to reduce the availability of prescription opioids as a way to stop this problem; however, unfortunately, if that is done too abruptly, in the absence of available treatment, it will drive more people to switch to using illicit drugs, which increases the risk of overdose. In the long run, it will be important to reduce the widespread availability of opioids in order to reduce new initiates to opioid dependence.

“Rhode Island boasts one of the most progressive set of clinical guidelines for the treatment of chronic pain in the country, with a forthcoming plan to enforce them. The state has an online accessible prescription monitoring program with an increasing number of health professionals registered and poised to use it, and is home to several institutions that have embraced aggressive three-day prescribing limits for opioids obtained from the emergency department. These and other local efforts to improve safer prescribing are noteworthy and necessary; they are well underway. This strategic plan is not meant to duplicate or circumvent these efforts.

“This plan assumes a collaborative approach; it considers interventions aimed at both supply and demand, as well as those aimed at harm reduction. It further asserts that the big-picture goals are to generate positive relationships with the most vulnerable of populations affected by addiction and overdose, to provide evidence-based treatment at every opportunity, and to support the pursuit of lifelong recovery. Support across Rhode Island – from hospital Emergency Departments to police patrol cars to abandoned street corners – is needed for our efforts to be successful. Thousands of lives hang in the balance."

[Feel free to cut and paste and share this on social media with your colleagues, friends and families – and with your elected officials.]

A deeper dive

The strategic plan begins an ordering of the problem, focused first on medication-assisted treatment, under the premise that “every door is the right one” for treatment, in order to contain and better manage the plague of opioid addiction. [It reflects perhaps a bias toward medical intervention as an evidence-based approach more easily delivered and measured within the current health care delivery system.]

In particular, it recommends expansion of what’s known as medication-assisted treatment at every location where opioid users are found – including emergency rooms, hospitals and clinics, the criminal justice system, and opioid treatment programs.

The specific focus is on the increased use of the drug, bupremorphine, which, like methadone, is a medication used for detoxification, in both short-term and long-term opioid replacement therapy.

The plan offered evidence to support medication-assisted treatment, claiming it reduces the risk of death, relapse, chance of going to prison, and improves quality of life.

By the numbers, the plan states that one-fifth of all fatal overdose victims in 2014 and 2015 were incarcerated in the prior two years – roughly 77 Rhode Islanders.

Further, the plan says that about 250 individuals enter prison every year on medicated-assisted treatment, and are either “detoxed” if on methadone or provided no taper schedule if on buprenorphine.

• To remedy the problem of access for prisoners, the strategic plan proposes to offer medication-assisted treatment in prison and jail, and to also start medication-assisted treatment prior to release, with community referral for ongoing medication-assisted treatment.

In hospital emergency rooms, the number of visits for drug abuse for heroin or other opioids has soared, with some 1,250 annual Emergency Department visits logged in during 2013, according to the plan.

• To address the problem at this point of entry to the health care delivery system, the strategic plan recommends educating and encouraging Emergency Department providers to start using buprenorphine, followed up with an appointment for continued treatment with properly credentialed physicians in the community.

The plan said that in 2014, there were some 4,500 individuals on methadone in Rhode Island, as well as some 4,662 individuals who were treated with buprenorphine under the care of a physician, many apparently for detoxification. However, the plan continued, there were no opioid treatment programs providing buprenorphine.

Further, the plan said that were fewer than 75 physicians in Rhode Island that were properly credentialed to provide buprenorphine for office-based opioid therapy, with each having the ability to treat up to 100 patients. Only 43 physicians in Rhode Island were treating more than 50 patients a year, according to the plan, indicating that there many such providers were not operating at capacity.

• To remedy that existing gap in capacity, the strategic plan recommended that medication-assisted treatment be expanded in high-volume provider sites, including opioid treatment centers, community health centers, community-based treatment programs, group practices, and at the Lifespan and Care New England hospitals, including Butler Hospital.

It also called for a reduction in payment barriers to opioid treatment programs and an expansion of the use of bupenorphine and naltrexone in addition to methadone, developing an alternative payment methodology.

To accomplish all this, the strategic plan recommends creating what they call “Buprenorphine Centers of Excellence.”

Naloxone as a standard of care

The reversal strategy within the strategic plan is focused on making the use of naloxone as a standard of care, because of its ability to save lives by reversing the severe respiratory depression caused by opioids.

On the good news side, the strategic plan reports that the provision of naloxone has ramped up considerably, with the majority of that effort has been through community-based organizations. In addition, more than half of all Rhode Island police departments have been trained in how to administer naloxone and been equipped with it.

On the bad news side, the cost of naloxone has increased to unsustainable levels and threatens the existence of the community programs as well as fledgling police programs.

More troubling, perhaps, was that none of the 2015 reviewed deaths noted naloxone, either community or individually acquired, being administered prior to ambulance arrival. [This speaks directly in part to the ongoing controversy regarding reauthorization of the Good Samaritan Law.]

Also noted by the report was the fact that in 2014, there was an increasing number of fentanyl overdose deaths that involved cocaine, without heroin, indicating the need for a highly flexible response and the ability to work closely with high-risk populations.

The strategic plan recommends a three-pronged approach to increase the availability and use of naloxone:

• The creation of a designated fund for state-purchase and distribution of naloxone, coordinated by the R.I. Department of Health, with a medical director overseeing the program, leveraging existing disaster medication purchasing procedures.

• An aggressive outreach campaign to high-risk individuals, after a non-fatal overdose, including access to recovery coaching, naloxone provision, and facilitated treatment entry to survivors, their families, and their network.

• A new requirement that pharmacists must offer naloxone to all patients whose prescriptions are being filled for Schedule II opioids and for all co-prescriptions of a benzodiazeprine [an anti-anxiety medication] and any opioid medication. Patients would be required to opt out [sign their name] if they wish to decline the naloxone medication.

Safer prescribing and dispensing

The third leg of the strategic plan begins to address one of the causes of the drug overdose epidemic: the prescription of opioids when lethally mixed with the prescription of benzodiazepines, or anti-anxiety drugs.

The strategic plan presents a straightforward approach to the problem and the solution.

Unsafe combinations of prescribed medications are linked to addiction and to many overdoses, and are preventable. Benzodiazepines were involved in one-third of all confirmed overdose deaths in 2014-2015 – some 126 deaths, according to the plan.

Rhode Island, in turn, ranks fourth in the U.S. for benzodiazepine use per capita.

And, the co-dispensing of benzodiazepines with an opioid within a 30-day period is a common practice, increasing for adults as well as for young adults under the age of 19.

Not surprisingly, treatment admissions for benzodiazepines as a secondary substance of abuse has substantially increased in recent years, according to the plan.

The strategic plan’s prevention plan to reduce the dangerous prescribing of benzodiazepines, which, when combined with opioids, can impair breathing and cause death, is to strengthen the state’s Prescription Monitoring Program.

• To reorient the Prescription Monitoring Program to structure “alert” messages to prescribers and pharmacists when a patient’s medications currently include a combination of opioids and benzodiazepines.

• To encourage a standardized used of urine drug testing that can identify “co-ingestion” of both kinds of medications at opioid treatment programs and other health care settings.

• To provide a prescription for naloxone as risk mitigation.

• To educate both prescribers and patients about the dangers of mixed use with aggressive safety messaging.

This strategy seeks to reduce dangerous prescribing of benzodiazepines, which combine with opioids to impair breathing and cause death.

Expand recovery supports

By the time the reader arrives at the last leg of the strategic plan, recommending the large-scale expansion of recovery coach reach and capacity, it’s easy to become overwhelmed by the details. That’s a shame, to use a stigma-inducing word.

The strategic plan says it very well: “The growing need and capacity for recovery services mirrors the pace of the epidemic. Successful recovery nurtures the individual’s health, home, community, and purpose. New opportunities are envisioned that support peer recovery services and medication assisted recovery.”

By the numbers, recovery coaches saw more than a third of all overdose victims at the busiest emergency rooms in the state, providing care and recovery supports to more than 110 individuals. [God bless Jim Gillen, one of the creators of the program.]

In addition, recovery coaches who were part of the Anchor ED initiative were successful in securing treatment and recovery supports some 83 percent of the time.

The strategic plan recommends that peer recovery coach services, with naloxone provision, be implemented at every Emergency Department in Rhode Island, in hospitals to support addiction consultation services, in the criminal justice system to support medication-assisted treatment upon return to the community.

“Every effort should be made to expand and create consistency in reimbursement for delivery of certified peer recovery coach services,” the strategic plan recommended. “Anticipated cost-savings of expanded recovery resources include fewer emergency department visits, inpatient hospitalizations, incarcerations, treatment episodes, and custodial and foster care services.”

The problem is, of course, who’s going to pay for this expansion, even if the cost-savings can be quantified? The continuum of peer recovery coaches and supports does not fit well within the clinical model of care and health insurance reimbursement practices under the current health care delivery system, which often puts more value on academic credentials rather than street cred and expertise.

From a larger perspective, it’s often still the doctors, in a position of authority, telling the patients what’s best for them and their lives. Or, the police and the criminal justice system. The continuing support network of peer recovery works on a different – and often more effective – model.

The strategic plan appears to be a great step forward, prepared with much insight by Traci Green, Ph.D., and Dr. Jody Rich. The proof will be in how it is implemented, and how much in resources are invested, and where those resources get allocated.