If you want to improve education in RI, get rid of the lead

New study focused on Rhode Island schoolchildren links poor performance on third-grade testing to lead poisoning

Lead poisoning is a preventable, man-made scourge. Once children are poisoned, it is not clear how best to repair the damages. The dangers of lead have been known for more than 2,000 years. Still, we shake our heads in disgust and amazement at the latest news stories, such as the one where residents in a housing project in Indiana were forced to move because their homes were built on land adjacent to a lead smelter.

The larger question is: what kinds of political action are we willing to take to remove lead from our environment? It is now a personal question that I must confront in my own life, knowing that lead in my drinking water may be poisoning me. Am I willing to challenge the landlord to take action to protect me? Am I willing to demand that the city to take action to protect me? What is the cost that I am personally willing to pay? Or, do I just try to find a new place to live? Stay tuned.

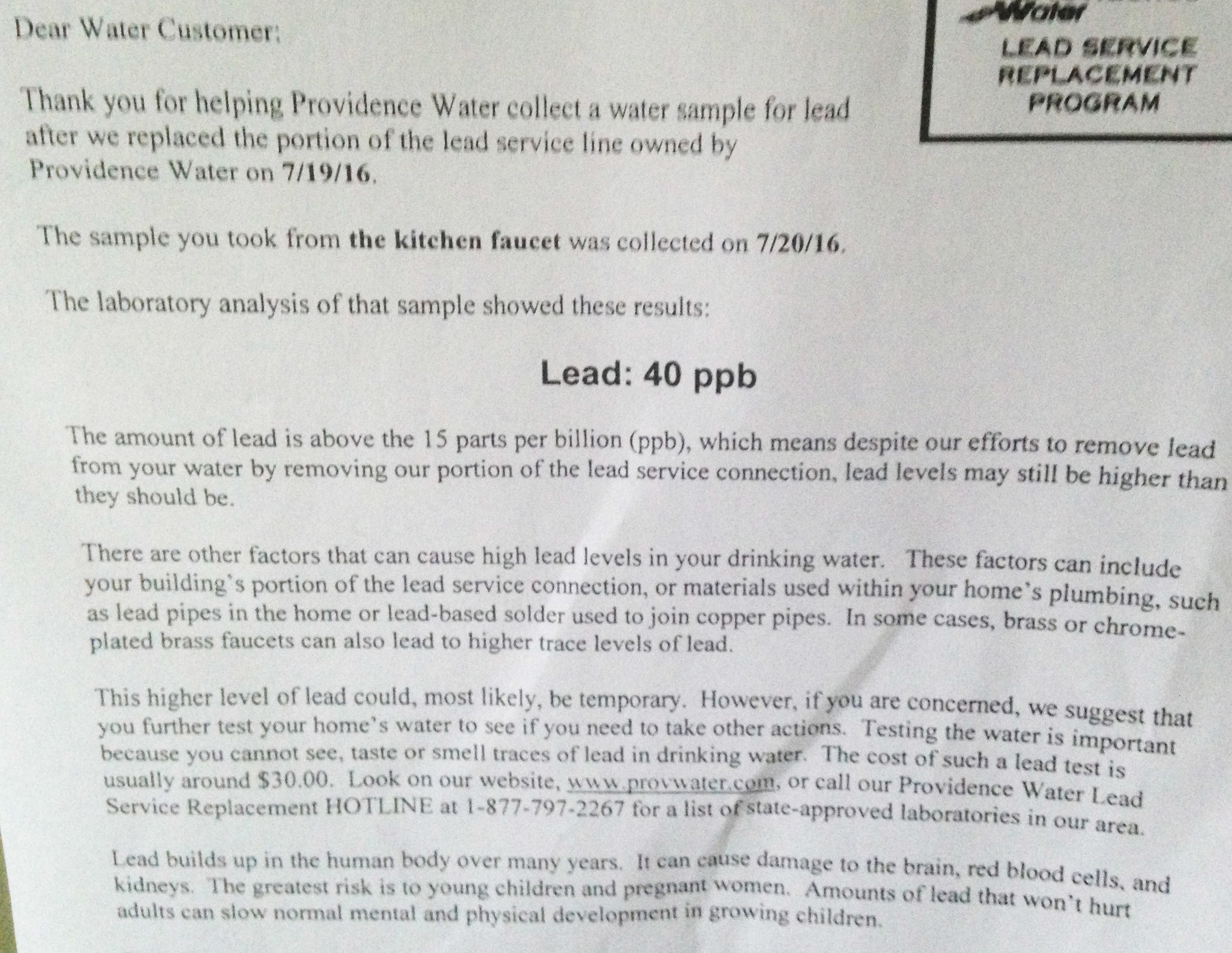

PROVIDENCE – In the foyer of the apartment building where I live, there was a copy of a letter that had recently been sent to one of the tenants, taped to the inside of the door. She had had her kitchen water faucet tested for lead.

The news was not good: Providence Water Supply Board had found that there were 40 parts per billion of lead in the tap water. The federal water standard is 15 parts per billion. Of course, the reality is that there is no safe level of lead.

It was humbling to learn about this dismal reality, given how often ConvergenceRI has published stories in the last three years about lead poisoning, including the top story from last week, “Looking for lead [in all the wrong places],” that the water I used for drinking, cooking and washing was likely to be poisoning me.

I was now a participant in the news story I had been so diligently covering.

The other reality is that the first four remedial corrective actions offered by Providence Water were helpful but placed the responsibility on fixing the problem on the consumer, not on the landlord or the water company.

• Flush your pipes, running the water for two minutes before using.

• Use only cold water for cooking and drinking.

• Remove debris from faucet strainers/aerators regularly.

• Install a point of use home treatment device, such as a tap filter or countertop filter.

The fifth recommendation did begin to address the root issues: replace internal plumbing, such as lead-based soldered pipes and brass/chrome-plated faucets, which may contain lead. Great advice. Should I pass that advice onto the landlord with the next rent check?

“Everything coming through the Scituate Reservoir and coming through our thousands of miles of mains is clean,’’ said Dyana Koelsch, a spokeswoman for the Providence Water Supply Board, responding to a question from AP reporter Matt O’Brien about the reasons behind why Providence was one of the largest U.S. water systems to violate lead standards, in a story published April 9, 2016, in The Boston Globe. ‘‘Our vulnerability is the lead service pipes from the public main to the curb and, even if we fix that, from the curb to private homes.’’

More than just removing service lines, one pediatrician told ConvergenceRI, an effective strategy needs to deal with interior paint, interior pipes and solder as well. “Either you treat the entire home and make it lead safe or the exposures will continue,’’ the pediatrician said.

Dog and pony show in Providence

The news media and community advocates were out in full force when U.S. Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julian Castro visited Providence on Wednesday, Aug. 31, holding a news conference hosted by Sen. Jack Reed at the Hartford Park Tower Community Room at 335 Hartford Ave.

At the news conference, Castro announced that HUD was proposing rules to lower the threshold for lead poisoning in a child’s blood to 5 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood from the current standard of 20 micrograms, in order to be aligned with the standard used by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It was national news.

Earlier in the day, in a media photo op, Castro had toured a Providence home where a federally funded cleanup project was removing lead paint.

All the usual suspects were there at the news conference, singing the deserved praises of Reed’s leadership as a forceful advocate in fighting lead poisoning in children.

Joining Castro and Reed on the podium were Providence Mayor Jorge Elorza, Rep. David Cicilline, Rep. Jim Langevin, R.I. Housing Director Barbara Fields, and Dr. Nicole Alexander-Scott, director of the R.I. Department of Housing.

In the audience were a number of elected officials, including Rep. Eileen Naughton, who will be leading a commission looking into the dangers of lead in drinking water in Rhode Island, Central Falls Mayor James Diossa, and state Sen. Juan Pichardo, among others.

During the May 23 visit by Dr. Linda Birnbaum, director of the National Institute for Environmental Sciences, hosted by Reed, Birnbaum had briefed government officials and community advocates that the CDC was considering taking action to lower the threshold of lead poisoning in children, to declare that there was no safe level, abandoning the current 5 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood as being too high.

Brief encounter

After the news conference, ConvergenceRI managed a brief two-minute interview with Castro.

ConvergenceRI: Although HUD has proposed lowering the threshold for lead poisoning from 20 to 5 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood, matching the current standard at CDC, there are ongoing conversations to lower that standard and say there is no safe level of lead.

CASTRO: Number one, our hope is that every single child will get tested. Not only those who are showing symptoms.

Secondly, of course, we’re going to follow the science and the CDC. We’re glad to bring our standard into sync with the best science that’s available at the CDC, and in the years to come, we look forward to remaining in sync with the CDC.

In fact, one of the elements of this rule proposal is that we would be able to make the change more easily in the future by notice instead of having to go to rule-making, so that we can keep our standard in sync with the CDC, whatever level that goes to.

ConvergenceRI: What about the kids who have already been poisoned? What kinds of mitigation and intervention should there be after kids have been identified as being lead poisoned?

CASTRO: As part of this rule, what we are saying is, in HUD-assisted properties, when there is a child under the age of six who is identified as having elevated blood lead levels above the standard, a full environmental assessment has to be done in that property.

I will also say that we know we’re not alone in this; our partners are also our hospitals, our schools, and others that test and treat children who have elevated blood lead levels. We work within an ecosystem of partners determined to keep children and families healthy.

The really big story

The really big news story about lead poisoning, with a huge local angle, was not covered by any of the local news media.

It was, however, the focus of a column by Paul Krugman in The New York Times on Sept. 2.

Krugman wrote: “I’ve just been reading a new study [emphasis added] by a team of economists and health experts confirming the growing consensus that even low levels of lead in children’s bloodstreams have a significant adverse effects on cognitive performance. And lead exposure is still strongly correlated with growing up in a disadvantaged household.

But how can this be going on in a country that claims to believe in equality of opportunity? Just in case it’s not obvious: children who are being poisoned by their environment don’t have the same opportunities as children who aren’t.”

The study, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, focused on education outcomes for Rhode Island children who had been poisoned by lead. [See link to study below.]

The study was written by Anna Aizer, a professor of Economics at Brown University in the Population Studies and Training Center department; Janet Currie, a professor of Economics and Public Affairs and director of the Center for Health and Well-Being at Princeton University, Dr. Peter Simon, an associate clinical professor in Pediatrics and Epidemiology at Brown University, and Dr. Patrick Vivier, an associate professor of Community Health and Pediatrics at Brown University, a pediatrician affiliated with Hasbro Children’s Hospital, and a member of the executive committee of the new Hassenfeld Child Health Innovation Institute.

The study constructed an individual-level longitudinal dataset that linked preschool blood lead levels with third-grade test scores for eight birth cohorts of Rhode Island children born between 1997 and 2005. It found that decreases in average blood lead levels reduced the probability of below proficient reading skills.

“Poor and minority children are more likely to be exposed to lead, suggesting that lead poisoning may be one of the causes of continuing gaps in test scores between disadvantaged and other children,” the study concluded.

Translated, if you want to improve test score performances in Rhode Island, the priority should be to invest in removing lead from the environment – from substandard, poorly maintained older housing, from drinking water, and from the soil.

A next step, based on the study findings, would be to develop a five-year plan that identifies the likely mix of lead sources in all neighborhoods in both urban and suburban Rhode Island, as well as a way to score the risks, according to Simon.

“We would need to agree on the way to use the best data we have on lead in soil, water and interior dust and paint,” he said. “We might need to invest in some additional sampling of the three main substrates.”