In Rhode Island, money talks, regulation walks

What does it portend when CVS goes to Mattiello to rewrite public health licensing conditions it doesn’t like?

Were the conditions unfriendly to business and Rhode Island’s economy, as Mattiello claimed, or just thorns in CVS’s self-interest? Did the jettisoned conditions contain safeguards to protect Rhode Island’s public health and the future delivery of primary care, or were they overreaching?

The deal precluded a public, transparent conversation; it also underscored the need for a comprehensive statewide health care authority.

What does that mean for other health IT systems in the market?

How data is shared across systems – and the efficacy of the state’s CurrentCare, managed by the R.I. Quality Institute, with a limited number of participants – deserves more investigation.

Blackstone Valley Community Health Care has been able to develop the most sophisticated use of health IT at the point of care, bending the medical cost curve by $12 million over the last four years. But their ability to be rewarded is limited by the state’s current risk-sharing agreement.

A major driver of innovation within health IT will be the increasing dominance of mobile technology as the way that health care providers and patients communicate and share data across a team of care providers and family – particularly with the advent of Meaningful Use III.

In turn, the delay in the implementation of ICD 10, the coding used for medical billing, is an example of the way that hospitals and medical providers often have to jump through frustrating hoops that eat up limited resources.

PROVIDENCE – Politics is the story of who gets what, when and how, so there was nothing shy or surprising about the latest power move by CVS Caremark.

The retail pharmacy chain had been upset by the conditions imposed by Dr. Michael Fine, the director of the R.I. Department of Health, in a May 14 decision approving the licensing of seven MinuteClinics in Rhode Island, following an involved, lengthy public process before the R.I. Health Services Council.

In response, the Woonsocket-based corporate behemoth, which earned $126 billion in revenue and $8 billion in operating profits in FY 2013, went straight to the offices of Rep. Nicholas Mattiello, the new R.I. Speaker of the House, to get the conditions watered down.

Mattiello, in turn, called Gov. Lincoln Chafee. Behind closed doors, in private, in a meeting that included Richard Licht, head of the R.I. Department of Administration, and Peter Marino, director of the R.I. Office of Management and Budget, as well as CVS and MinuteClinic officials, discussions were held on how to cut out conditions that CVS didn't like.

In doing so, CVS chose to bypass direct engagement with Fine, creating what Dr. Elizabeth Lange, a pediatrician, called “unfortunate precedent,” one based upon political leverage and not on public health.

“I don’t know exactly what happened; what I do know is that a very public process became a private negotiation,” she told ConvergenceRI. [The final revised version apparently did involve some further discussion and some back-and-forth negotiations with Fine.]

The outcome is problematic, Lange continued. “The decisions made by Rhode Island’s senior health care official about state public health needs were circumvented,” Lange said.

Steven DeToy, spokesman for the R.I. Medical Association, was more blunt in his assessment. “It’s the story of a disparate group of individuals, primary care providers, [fighting] against one big corporation – life as it is in Rhode Island.”

Mattiello, for his part, was more than happy to carry the water for CVS, because he believed that “CVS was being unfairly treated, and that Rhode Island needed to be more business friendly,” Larry Berman, Mattiello’s spokesman, told ConvergenceRI.

Mattiello proudly championed his successful intervention. “Speaker Mattiello met with CVS, MinuteClinic and state officials to express his concerns regarding burdensome regulations and conditions that were initially put into place by the Department of Health,” according to a statement issued by Berman, as reported by The Providence Journal.

Mattiello, Berman continued, “was pleased to have been able to facilitate a positive result for one of the state’s largest businesses that will be adding jobs through seven MinuteClinics. He will continue to oppose overbearing regulations that hamper the growth of Rhode Island’s economy.”

But, were the conditions really that overbearing? How exactly would they truly have hampered the growth of Rhode Island’s economy – beyond CVS’s own self-interest?

Instead of an engaged, transparent, public conversation, it ended up being a backroom deal – an outcome tinged with irony, given the current cathartic debate about whether or not to repay the debt caused by the failed investment in 38 Studios, the result of a previous backroom deal.

In the long run, it may not be the R.I. Department of Health that got thrown under the bus, but primary care providers, access to charity care, and improved public health outcomes for Rhode Islanders.

“Meet the new boss…”

CVS is no stranger to throwing its political heft around at the State House. In 2013, it successfully fought the Chafee administration’s efforts to trim a tax break for the company that netted it $14.5 million in tax relief by threatening to “reassess” its workforce commitment to Rhode Island.

This year, it successfully bid to become the manager of the state employee’s pharmacy contract for three years at $158.1 million.

One of the economic arguments advanced by CVS in support of MinuteClinics was that the move would support the creation of as many as 200 jobs in Rhode Island – including the staff at the seven MinuteClinics operating here in Rhode Island but mostly at CVS headquarters in Woonsocket, employees that were responsible for the overall coordination efforts at MinuteClinics that now operate in 28 other states and the District of Columbia.

In a state with chronic high unemployment, it may appear difficult to argue against the promise of jobs by one of the state’s largest private employers – unless you fully understand and grasp what’s on the other side of the ledger.

There are some 982 primary care physicians – many of whom operate as small businesses – who generate about $1.047 billion a year in revenue, creating 5,498 jobs that produced $792 million in wages and benefits, according to a 2011 Lewin report that can be found on the R.I. Medical Society website.

The most recent economic analysis, published on April 16, suggest that primary care physicians are responsible for about one-third of $4.8 billion in annual revenue, or $1.6 billion, according to DeToy.

An impressive number, $1.6 billion, especially when coupled with the projected double-digit job growth in Rhode Island’s health care sector, the state’s largest private employment sector, according to the recent analysis by the R.I. Governor’s Workforce Board. But, unlike CVS, primary care physicians as a group, much like many other small businesses, lack market power and political pull.

As Fine said in a news release following the initial May 14 decision, “Primary care practices have been significantly challenged by the necessity of functioning as businesses in a world in which they have no effective market power, while obligated to meet regulated standards of professional practice, and by their own ethical commitments.”

Without any statewide planning authority, the coordination of primary care has become fragmented – despite numerous studies that show that emphasis on primary care creates improved population health outcomes at the lowest medical cost.

Further, with the advent of health care reform, the current health care delivery system in Rhode Island is in flux – as the in-patient, hospital-as-hotel business model evolves to an out-patient, patient-centered, team-based system of delivering health care, moving away from fee-for-service toward global payments.

The recently announced partnership of Care New England, Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Rhode Island, and R.I. Primary Care Physicians in an Accountable Care Organization payment model for Medicare Advantage patients is an example of the smart, innovative approaches now underway in Rhode Island.

But that evolution, no matter how promising, has been slow and methodical, and takes time. [It has been encumbered by the continued consolidation of hospital systems and group practices in what one observer recently likened to a game of musical chairs – with no one wanting to be left without a seat when the music stops.]

The market waits for no one – and CVS has moved aggressively to fill the niche with MinuteClinics in seven Rhode Island communities, including Cranston, North Smithfield, Wakefield, East Greenwich, Providence, Westerly and Woonsocket.

The MinuteClinics are to be staffed by nurse practitioners and seek to provide customers with convenience for “routine” care – throat swabs for strep, for instance – that can be difficult to come by in a timely fashion at primary care offices, given the high demand and the wait-time.

In approving MinuteClinics in Rhode Island, in his initial decision, Fine acknowledged the consumer demand for more convenient services. He wrote: “MinuteClinic provides evidence of a consumer demand that is not being met in the current health services delivery marketplace. Response to that demand should not be suppressed but rather embraced, if the term “patient-centric” is to have any meaning at all.”

Further, Fine said that there was room in the market for both new models of primary care delivery and MinuteClinic. The primary care delivery community, he continued, if it acted together, could make trivial any potential damage caused to their business model from MinuteClinic.

Fine, who called CVS a “great Rhode Island company,” also pointed to the successful influence that the primary care community had on CVS when it criticized CVS’s prior unsuccessful application for MinuteClinics in Rhode Island, given its sale of tobacco products. That had some influence on the CVS’s decision to go tobacco-free and exemplified “the notion of health in all policies,” according to Fine.

What’s at stake in the changed conditions

What was the problem with the initial conditions? CVS has not commented specifically in public about what it found to be unfriendly to business. What can be determined is what changes occurred between the initial and final, revised conditions.

The initial decision had CVS dispensing charity care at all of its seven MinuteClinic locations; the rewritten decision now has CVS dispensing charity care only to the patients of the R.I. Free Clinic – adults who are uninsured, and who must qualify to become patients of the clinic through a monthly lottery, because demand is so high.

Specifically, under Condition No. 22, the MinuteClinics were required to offer charity care services to any patient who qualified for free care as having income less than 200 percent of the federal poverty guidelines and who had documentation for eligibility for such care from a Rhode Island hospital, a community health center, a free clinic, or a community mental health center. The charity care requirement was limited to two visits a year for each eligible patient and up to 5 percent system-wide in the state.

In his decision, Fine explained that CVS’s relationship with the R.I. Free Clinic, which because it has a limited patient roster and only one location, did not appear to offer appropriate access to underserved populations envisioned by Rhode Island's charity care law by an organization with seven locations.

Currently, CVS provides pharmacy benefits for generic prescriptions at two retail pharmacy locations in Rhode Island for patients of the R.I Free Clinic. The more expensive prescriptions of named drugs are prepared through a community pharmacy formulary partnership. [First Lady Stephanie Chafee was a founder of the R.I. Free Clinic.]

In 2013, the R.I. Free Clinic served 2,059 patients, according to Julie Karahalis, development director at the R.I Free Clinic. Because the demand for services has been so high, patients have been selected through a monthly lottery. That process is expected to change within the next month, opening more slots for patients, according to Karahalis.

In total, Karahalis estimated that there were about 50,000 adults in Rhode Island who were still without health insurance, many of whom were working, because the premiums, the co-pays and the deductible were still too expensive.

The R.I. Free Clinic, though its own Affordable Care Act project consultant, has helped about 400 patients to sign up and access health care through HealthSourceRI, where applicable and appropriate, according to Karahalis.

Details have not been fully worked out regarding the partnership between the R.I. Free Clinic and CVS regarding access to its MinuteClinics, which would provide access to patients beyond the normal hours of the R.I. Free Clinic at the first two of the MinuteClinics scheduled to open.

The question is: was the cost of providing charity care – limited to two visits a year by a patient, and 5 percent of the total number of visits statewide at the seven locations – really a deal-breaker for CVS?

How much would it have added to the projected cost of providing some access to the roughly 2,000 patients of the R.I. Free Clinic, many of whom are centrally located in Rhode Island’s urban core and unlikely to find themselves going to MinuteClinics in East Greenwich, Wakefield, North Smithfield or Westerly?

Access to primary care

Another deleted condition, No. 5, attempted to reinforce access to primary care, by requiring that for each MinuteClinic which could not locate a primary care provider within a five-mile radium to accept a referred patient, CVS would donate an annual contribution of $25,000 to the R.I. Physician’s Loan Replacement Fund, set up to pay back medical student loans who go into primary care and practice in Rhode Island.

At first glance, this might appear to be a case of an “overbearing” regulation, as defined by Mattiello.

But Fine’s decision reflected the fact that MinuteClinic’s successful economic operation very much depends on the existence of a robust primary care infrastructure in Rhode Island, enabling the retail clinic with its limited scope of services to have somewhere else to refer patients with presenting problems it cannot address.

Fine explained his reasoning: “Contrary to MinuteClinic’s representations, there is no documented shortage of primary care in Rhode Island, which ranks eighth in the nation for primary care supply.”

Fine continued: “But there is no reason to think that primary care practice is evenly distributed across the state, or that supply will be able to keep up with new demands imposed by the Affordable Care Act, or changes in the incidence and prevalence of disease, and the development of new technologies, which bring with them new primary care responsibilities and added workload.”

The safety of the MinuteClinic’s clinical model, Fine said, depends on the existence of a robust primary care infrastructure. As a result, patients can be referred to primary care providers if their presenting complaint does not fit within MinuteClinic’s scope of service, if the patient presents with behavioral or mental health concerns [between 28-56 percent of the current primary care workload], or should the patient have a serious or complex medical issue.

In other words, the condition asked CVS to contribute to support the primary care infrastructure it depends on to make its profits by dispensing limited, convenient services. The condition only kicked in if a MinuteClinic was unable to make a referral of a patient that was accepted by a primary care practice in a five-mile radius – an indication that there was indeed a problem of access.

In total, in the most expensive, extreme case, $25,000 a clinic, or $175,000 a year, would be donated to a loan fund to help attract and retain primary care providers in Rhode Island by forgiving medical school loans. It would also appear to be tax-deductible.

Once again, the question is: was the potential maximum donation of $175,000 a year, less than .002 percent of its annual profits, a deal-breaker? If CVS is going to benefit directly from the existence of a primary care infrastructure – the roadway to care – that makes its business model possible and profitable, does it have a responsibility to contribute toward a solution if future access becomes problematic?

It’s a good question – one that could have been debated openly, in public, in a transparent way, rather than nixed in a backroom deal.

Moving forward

Beyond the immediate results of CVS being able to revise what it considered to be problematic conditions to its bottom line, the ability of political leaders to rewrite conditions behind closed doors raises questions about how future health care policy decisions will be made – and by whom.

Lange told ConvergenceRI she was worried that the new rewritten conditions could open “a floodgate” of retail based clinics in Rhode Island housed at big retail stores such as Walmart, Target, Rite Aid and Walgreens.

“As a pediatrician, I look at development, and what happens when one parent doesn’t give the answer the child likes, so the child keeps bullying and pushing the other parent until [he or she] gets the answer they like.”

The rewritten conditions, she said, “are an unfortunate precedent” that reward such behavior.

A more fundamental question is whether the R.I. General Assembly will move forward with legislation to create a statewide health planning authority.

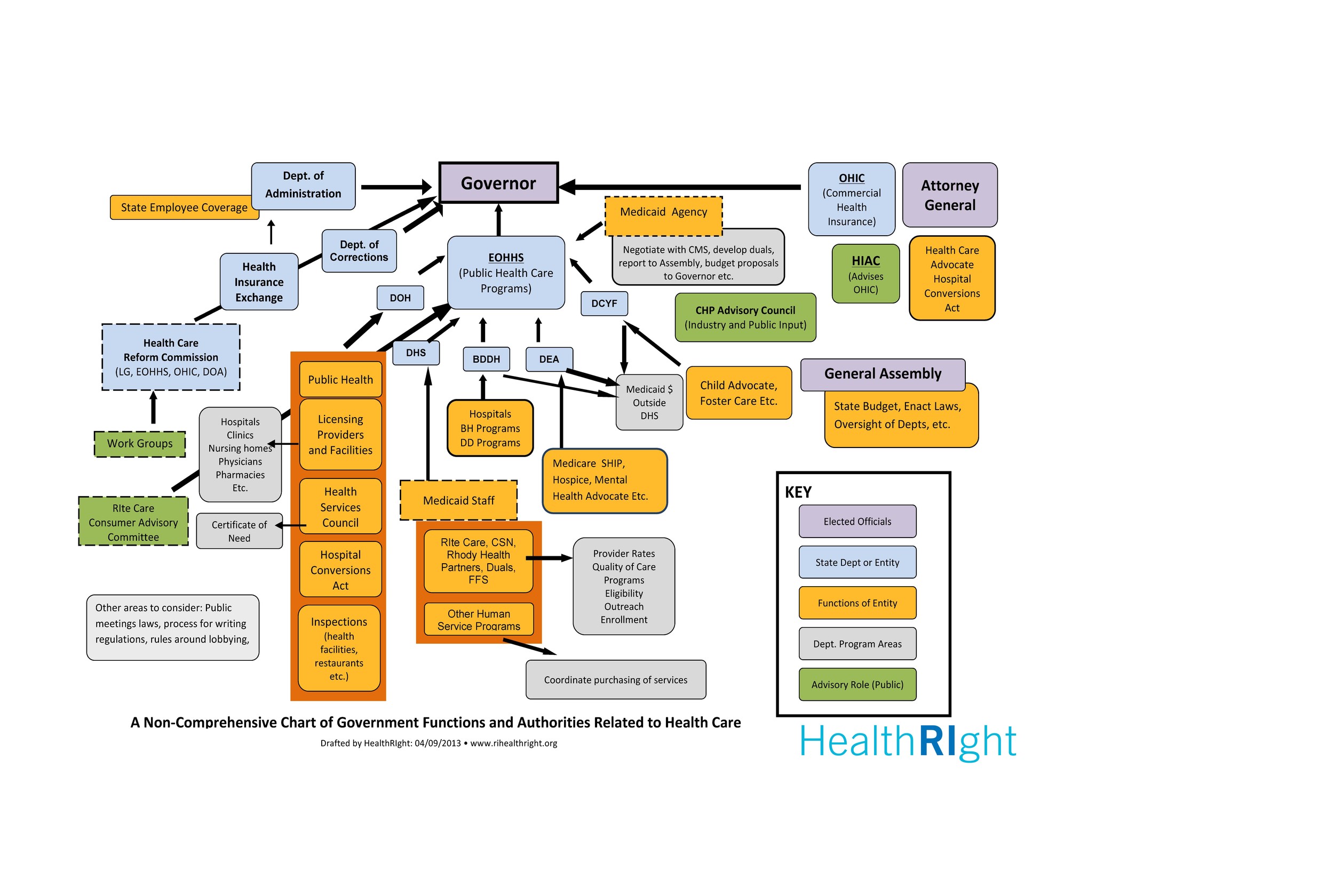

There are two pieces of legislation currently pending this year – a bill sponsored by Sen. Joshua Miller to create a statewide office of health policy, and another bill sponsored by Sen. Gayle Goldin and championed by HealthRIght to create a statewide healthcare authority that would serve as an active purchaser, consolidating the purchase of health insurance to create a market-driven approach to cost-controls for health care.

Rhode Island’s lack of ability to conduct comprehensive statewide planning is the bigger problem exposed by the CVS MinuteClinic episode, according to DeToy.

“We don’t have a comprehensive statewide health care plan; without that plan, it doesn’t matter how you get to the bottom line,” DeToy told ConvergenceRI. "The whole system is fragmented, because we don’t have health care planning. It’s very critical. We’ve been saying this for 10 years – we need to have a mechanism for determining need and how it should be constituted in the delivery of health care services.”

DeToy agreed with Dr. Alan Kurose, the president and CEO of Coastal Medical, that it is a role that government needs to play, because the private sector cannot be responsible for it. “That’s the nature of business – that’s what CVS did, to make the conditions fit their preferences.”

With planning, DeToy said, the state can decide what is needed in terms of the number of hospital beds, the number of hospice care centers, the need for skilled nursing facilities.