Looking for a sanity clause in Rhode Island

Four new studies offer detailed analysis in the cost, supply, demand and infrastructure of the state's behavioral and mental health systems of care

PROVIDENCE – While most of the news media were consumed with the task of digging through hundreds of thousands of pages of discovery released on Sept. 24 in the civil lawsuit filed over the alleged fraud in the 38 Studios debacle, ConvergenceRI instead chose to pore over the hundreds of pages in documents from the four Truven Health Analytics studies quantifying the costs, the demand, the health care supply and the analyses of Rhode Island’s behavioral health conundrum.

And, while the public release of the 38 Studios resulted in a splash [how many times did we see images of a band of reporters huddled in front of their laptops on TV screens, with the talent on camera breathlessly reporting on what they found so far], there has been little if any noise around release of the Truven Health Analytics studies, which were submitted as a package on Sept. 15.

What the 38 Studios revealed was the apparent loss of memory by many of the leading characters in the tragedy, a health condition that might be described as the onset of severe political dementia, not being able to remember or recall their conversations, their emails, and their meetings. [Piecing together what actually happened may require the lawsuit to go to trial, or further criminal probes by state authorities into potential wrongdoing.]

In contrast, the Truven Health Analytics studies, commissioned by the R.I. Health Care Planning and Accountability Advisory Council at the behest of the R.I. General Assembly, presented, in voluminous detail, the facts and financial charts that mapped the state’s behavioral and mental health landscape.

Much of what the studies found did not paint a pretty picture; the studies did, however, attempt to frame the issues with recommendations on how Rhode Island might move forward. These included discussion about moving toward population health and a coordinated, continuum approach to care. But, for whatever reasons, health equity and health disparities, and potential solutions to address social determinants of health did not emerge as prominent elements in the strategy.

The need to refocus and redirect resources to prevention and early intervention, instead of reaction and treatment, was also identified. The studies also spoke about the “glue” needed to bring together a comprehensive, coordinated approach. However, they did not address the apparent elephant in the room: the consolidation of behavioral health services within the larger framework of competing hospital systems, and how that has affected the interoperability of services and, in turn, undercut outlying community mental health services.

Four fact-based, evidence-based studies now exist that detail Rhode Island’s behavioral health conundrum. The unanswered question is this: whether there is the political will to invest the necessary resources to change the state’s trajectory. If nothing else, the state’s political leadership cannot now claim the onset of political dementia. It remains to be seen if they can cross the big river denial.

The cost findings

There’s much to chew on in what these studies found and quantified:

• In total costs, Rhode Island spends more on direct and indirect behavioral health than most other states, some $853 million on behavioral health treatment in 2013.

• At the same time, public financing for behavioral health care for adults and adolescents dropped by about 10 percent between 2007 and 2014, from $110 million to $97 million.

• State funding for substance abuse services dropped from about $15.5 million to $5 million between 2007 and 2014, despite the fact that Rhode Island adults die more frequently from narcotics overdose than adults in other New England states.

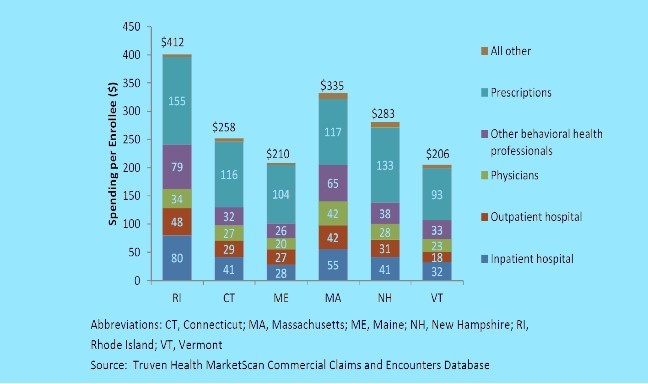

• The greatest cost drivers behind the reasons why Rhode Island spends more in total behavioral health care services are the costs of inpatient hospital care and prescription medications.

• In 2013, prescriptions accounted for 43 percent of the spending by Rhode Island providers for mental health treatment but just 13 percent for substance abuse treatment; at the same time, inpatient hospitals accounted for 18 percent of mental health treatment spending and 16 percent of substance abuse treatment.

• Adults in Rhode Island had the highest rate of psychiatric general hospital admissions among New England states and nationally.

• Medicaid was the single largest payer for behavioral health treatment in Rhode Island. In 2013, Medicaid financed $270 million in treatment spending, an amount equal to 33 percent of all mental health treatment and 19 percent of all treatment for substance use disorders. The Truven studies found that spending per enrollee was highest for adults between the ages of 25-64, with the vast majority being spent on mental health treatments.

• In 2013, the three largest private health insurers of Rhode Island residents (Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Rhode Island, United Healthcare, Tufts Health Plan) paid $150.7 million for behavioral health treatment – $130.3 million for mental health conditions, and $20.3 million for substance use disorders. This spending amounted to 17 percent of all mental health spending and 20 percent of all spending on substance use disorders. Of all treatment spending by Rhode Island’s private insurers, 9 percent was for mental health conditions and 1 percent for substance use disorders.

Similar to Medicaid, the vast majority of spending was for mental health treatment. The highest spending per enrollee was for adolescents aged 12-17.

• The estimated indirect costs of untreated mental illness from the R.I. Executive Office of Health and Human Services numbers and R.I. Department of Corrections numbers is calculated to be a total of about $276 million, which represents 12.8 percent of the total Department of Corrections budget and 3.15 percent of the total Rhode Island enacted budget for the year 2015

The cause findings: what’s behind the high demand?

The first of the Truven studies [which was actually published in April] found that Rhode Island faced a series of unique challenges [many of which have been documented by advocacy groups such as Rhode Island Kids Count when it comes to the health and well-being of children].

The study noted that a variety of factors – including biological attributes, individual competencies, family resources, school quality, and community-level characteristics – can increase or decrease the risk that a person will develop a mental or substance use disorder.

The Truven study found:

• Children in Rhode Island faced greater economic, social, and familial risks for the development of mental health and substance use disorders than children in other New England states and the nation.

• Unemployment among parents in Rhode Island is higher than in other New England states, more children live in single parent households, more children have inconsistent insurance coverage, and one in five children in Rhode Island is poor.

“These socio-economic challenges help explain why children and adolescents in Rhode Island experienced higher rates of adverse childhood events and subsequent behavioral health conditions such as ADHD, major depression, and illicit drug use than children and adolescents in other New England states and nationally,” the study said.

Further, the study continued, such “higher risk factors are expressed in adulthood as higher prevalence rates of disease.” Adults in Rhode Island have higher rates of drug abuse and dependence and serious psychological distress than other New England states and the national averages.

Some of the study’s other specific finding included:

• Children and adolescents aged 5-17 years in Rhode Island had higher rates of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and adolescents had higher rates of illicit drug use and marijuana use than the national average.

• Adults aged 18–44 years in Rhode Island had more general hospital admissions for mental health issues than similarly aged adults in other New England states and nationally.

• Rates of drug and alcohol use in Rhode Island often were higher than the national average, and adult residents had higher age-adjusted death rates from narcotics and hallucinogens than the national average.

• Many adults in Rhode Island were more likely to report unmet need for treatment of mental and substance use disorders than residents in the other comparison states.

• Compared with national and other New England state rates, Rhode Island had the highest rate of hospital admissions for mental health issues among individuals aged 18–44 years.

The supply side of the equation

The Truven study on supply side of the behavioral health landscape in Rhode Island begins with a positive reframe, looking at behavioral health providers and services for children and adolescents.

The study, completed in June, identifies that supporting the development of children requires an infrastructure be in place in more than one system – in public health, health care, education and community agencies – to support preventive interventions at numerous levels.

That education, policy and intervention continuum begins prior to conception, and flows through prenatal care, infancy, early childhood, childhood, early adolescence, adolescence and young adulthood.

The study defines the challenge for Rhode Island as its capability to moving the current system from the delivery of “reactive treatment” services to one that is focused on “prevention and early intervention.”

The Truven study further defined that behavioral health treatments fell into three categories: inpatient, outpatient, and medications or biomedical interventions. Inpatient was defined as short-term hospitalizations for life-threatening crises; in turn, outpatient care consisted of visits in which therapies or medications may be provided by an array providers – primary care physicians, psychiatrists, pediatricians, psychologists, social workers, counselors and nurses in a variety of settings.

Mostly importantly, the study pinpointed the weakness in what in termed the “scaffolding” of behavioral health services and interventions in Rhode Island: the scaffolding was insufficient to provide high-quality, cost-effective treatment, particularly for individuals with severe mental illness. Without the “glue” to connect these services, the severely mentally ill cycle in and out of hospitals, neglect their medications, become homeless or imprisoned, and are at a much higher risk of an early death. Sound familiar?

Specific findings in the supply side study included:

• The rate of homelessness among those served by the Rhode Island mental health system was higher than the national average (5 percent versus 3.3 percent). Yet, only 2.6 percent of individuals with serious mental illness served by the Rhode Island mental health system received supportive housing.

• Among Rhode Island Medicaid beneficiaries who were hospitalized for a mental illness, one in five had no follow-up mental health treatment in 30 days.

• After 2011, Rhode Island had no assertive community treatment programs. Additionally, Rhode Island lacks family psycho-education. The state should consider working these evidence-based practices into its community treatment framework.

• Rhode Island had a lower per capita number of substance abuse counselors and other behavioral health counselors than the national average. Rhode Island ranked lowest of all New England states for other behavioral health counselors and second lowest for substance abuse counselors, though other types of professionals (e.g., clinical social workers) provide counseling services in the state.

• Of the five counties in Rhode Island, three are designated as having at least one community health center with a shortage of mental health professionals: one in Newport County, six in Providence County, and one in Washington County.

• Rhode Island had no mental health programs offering specialized services for traumatic brain injury. It had the lowest percent of mental health facilities offering programs specifically designed for Veterans or for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease or Dementia in 2010.

• While Rhode Island appeared to have an adequate supply of behavioral health specialists, but they may not be accessible by those most in need or exist in the correct specializations for particular needs.

• There was a need to improve transitions across systems of care, particularly from costly inpatient and institutionalized settings, such as jails, to community settings.

Recommendations moving forward

If you’ve gotten this far into the story, which is clearly another deep dive by ConvergenceRI into the often murky waters of the behavioral health system in Rhode Island, here are, in briefest form, the recommendations moving forward presented by Truvin on Sept. 16 in a Powerpoint slide deck.

They are:

• Invest in proven, effective, preventive services and supports for children and families.

• Shift financing and provision of services away from high-cost, intensive and reactive services toward evidence-based services that facilitate patient-centered, community-based, recovery-oriented, coordinated care.

• Enhance state and local infrastructure to promote population-based approach to behavioral health care

No recipe book, however, is provided on how exactly to accomplish those recommendations.

Perhaps the best start for this effort will be the conversation/convergence to be held on Oct. 28 at Rhode Island College, entitled: Building a Collaborative Strategy To Reduce Toxic Stress in Rhode Island. Stay tuned.