RI medical researcher on verge of promising breakthrough in treating Alzheimer’s

Insulin, Alzheimer’s, and a new compound that appears to correct metabolic signaling abnormality

Unlike the accelerator model of economic development, the academic research model and the development of pharmacological products is more time intensive, but the ability to synthesize treatments that can address the scourge of Alzheimer’s disease has enormous economic dividends.

The focus on insulin – and Querfurth’s role as a principal investigator in a clinical study in using insulin in a nasal spray to treat Alzheimer’s – is equally promising in the way that clinical practice flows into research, and then back into practice.

If CVS Caremark is now banning tobacco products from its shelves, how long will it be before they consider banning sweetened, sugar-infused soft drinks? The role of insulin resistance – and the risk factor of Type 2 diabetes – in the onset of Alzheimer’s places renewed importance in rethinking the use and marketing of sugar, high fructose corn syrup, and sugar substitutes in our food and drink. Can you imagine a label being printed on sugar-laden soft drinks saying that consumption can be tied to Alzheimer’s disease, if the connection can be proven medically?

The study, by researchers at the Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, found that Alzheimer’s is rarely listed as a cause of death, but that autopsies of brains donated for research provided a more definitive diagnosis.

The total medical cost of Alzheimer’s in 2013 was estimated to be about $203 billion, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

PROVIDENCE – No one shouted wow! when Dr. Henry Querfurth, co-director of the Alzheimer’s and Memory Disorders Center at Rhode Island Hospital, finished his presentation at the recent MedMates event at RISD on Feb. 27.

As Querfurth himself told ConvergenceRI in a recent interview, he was the last of more than 20 presenters, and he wasn’t sure if people in the audience were still awake after more than five hours of presentations and panels.

But the work in Querfurth’s research lab is definitely worthy of at least a couple of wows, with exclamation points. Under his direction, his team of researchers – including several post-doctoral fellows and Brown students – has been able to identify a small molecule compound that appears to correct the metabolic signaling abnormality in the brain associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

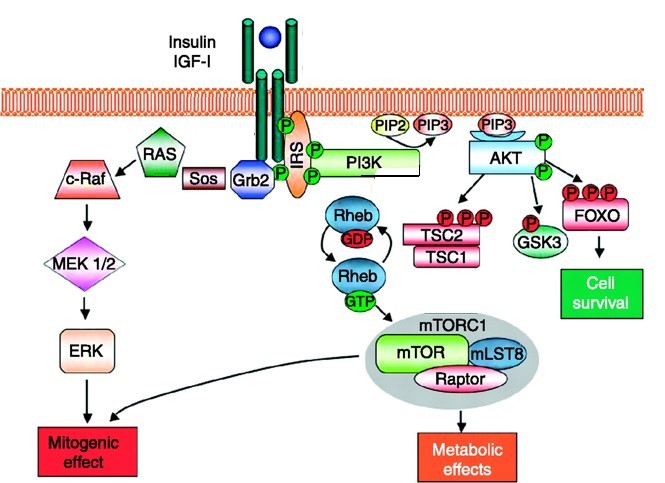

Querfurth’s work evolved from basic biologic inquiries regarding the role of insulin in neural signaling pathways into how it was that the amyloid associated with plaques and tangles formed in the brain outside the cells in Alzheimer’s patients developed from inside the cells.

“I found the target of intracellular amyloid before it escapes,” Querfurth told ConvergenceRI. “Now the research lab is 70 percent devoted to work on the compound that corrects the metabolic signaling abnormality.”

Moving from biology to translational research

Querfurth described the efforts as being at the early stage of drug discovery, moving from biology to translational molecular research.

“Some pieces of information are still missing,” he explained, relating to the efficacy of animal models with Alzheimer’s disease. “But I’m almost there,” Querfurth continued. “That, I’m told, is the kind of threshold that larger pharmaceutical companies would be looking at to provide future funding.”

The information at hand is a lot of molecular data, cell culture data, brain slice data, and some animal safety data, he explained.

Without giving away any trade secrets, Querfurth described the compound as a small molecule – not an antibody – that binds to a receptor area of the targeted enzyme. “There’s still room to explore the pharmacological space of this compound,” he said. “I have a pharmaceutical discovery company – a startup company in Boston – that is synthesizing brand new molecules, based upon the backbone of this molecule – to find others than are even more efficacious.”

For this work, there is some, but limited, NIH support.

In a nutshell, he continued, “It’s very exciting work. The lab, which was traditionally cell biology oriented, has become more focused on translational research.”

Querfurth, a working physician (who also has a Ph.D), still spends a good deal of his time seeing dementia and memory-disordered patients in the clinic at Rhode Island Hospital. “I evaluate many of the dementia patients in Rhode Island,” he said. As co-director of the Memory Disorders and Dementia Clinic, he holds a full clinic three times a week, sometimes seeing from four to five new patients and from eight to 10 follow-ups every day. "We also conduct several clinical trials in experimental therapies funded by various concerns," he said.

New lipid indicators for Alzheimer’s

Researchers recently unveiled a new study of a blood test that can predict – with accuracy – whether a healthy person will develop Alzheimer’s disease. The study, which was published in Nature Medicine, found lower levels of 10 particular lipids. The study found that the blood test predicted who would get Alzheimer’s or mild cognitive impairment with more than 90 percent accuracy.

As remarkable as the potential that the new study seems to indicate to develop a biomarker for the onset of Alzheimer’s disease, Querfurth said that he and other scientists might offer a slightly different view.

First, without a treatment, many might not wish to know. The new study is also highly experimental, technically involved, and needs replication, he said.

“A lot of this effort is focused on finding a biomarker for disease prediction,” he said. “A lot of money is being thrown at this strategy. But it’s not a direct pharmacological strategy, it’s a method to assess one’s risk for purposes of future drug trials in the hope to find a compound that will prevent disease.”

It’s quite different, Querfurth continued, from his work, which is focused on finding a drug that targets a pathway that is already affected in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

The other 30 percent of his lab's effort is on studying the other biologic processes in Alzheimer’s and related degenerative conditions.

One of the areas, he continued, “is a lipid study, in which we found one lipid very damaging to cell viability and another lipid that protects against the damaging lipid, another pathogenic processes in Alzheimer’s disease as brought out by the Nature Medicine study.”

The focus on insulin

In the last 15 years, Querfurth said that it had become apparent to researchers that Alzheimer’s disease is associated with a deficiency in amount or action of certain neurologic proteins that are essential to brain viability, response to stress, neurogenesis – the growth of neurons and their processes, connectivity and memory.

One of the key factors is insulin, he continued. “The brain apparently makes its own insulin,” Querfurth said. “Although insulin made in the pancreas does pass through the blood brain barrier, the brain has found additional roles for insulin. Insulin supports synaptic function and has anti-amyloid action in several respects.”

For scientists at the time, he continued, “that was a mind bender, that the brain makes use of its own insulin. And, it became clear from many epidemiological studies that diabetes – systemic insulin deficiency and systemic insulin resistance – is itself a risk factor for later cognitive decline, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease. There’s a significant two-fold increase in Alzheimer’s risk with Type 2 diabetes.”

Research has shown that insulin given to Alzheimer mice and applied to cultured cells has been found to be beneficial, according to Querfurth. His work has been focused on better understanding how the hormone insulin signals to the brain's interior milieu, and where in the multi-step chain of biochemical events it is disrupted in Alzheimer's disease.

Querfurth’s research has also focused upon is the way in which amyloids build up inside the cell, even before it escapes to become plaque. His yet unnamed compound reverses that effect on such amyloid on particular enzymes. “I don’t know anyone else who is working in that area,” he told ConvergenceRI.

One of the promising large clinical trials that is just starting up is a multi-site, randomized, double-blind control trial of insulin for Alzheimer’s disease. “Insulin is being given through the nose as a spray,” Querfurth said, who is one of the principal investigators, with Rhode Island Hospital as one of dozens of principal sites.

In search of collaborators

Querfurth is at the stage in his this type of drug discovery research, which is costly, where he is looking for potential collaborators, donors, and venture investors to assist in an effort to move forward with testing the unnamed compound – and other new compounds that are being synthesized – with animal models, before entering into clinical trials.

“The current, federally funded big clinical trial with intranasal regular insulin makes strategies like this one, which will improve or even surpass normal insulin's efficacy, even more desirable and important,” he said.