Encountering the history of the “disappeared” as a tourist

Visiting the former Naval Ex-Officer’s Club in Buenos Aires, once a place of torture, now a museum, recalling what happened when a dictatorship silenced dissent in brutal fashion

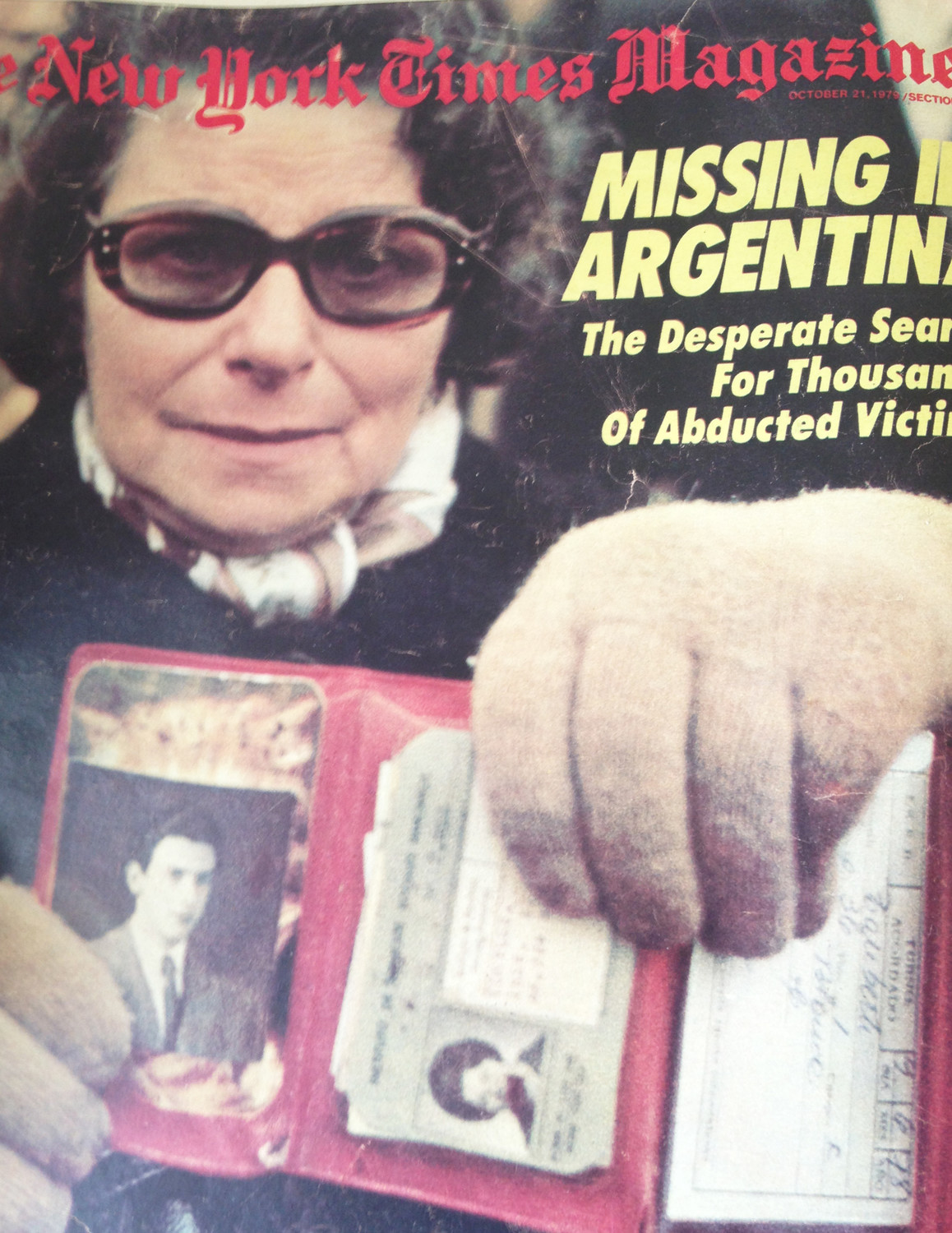

When the issue closed, I complained to one of the editors about the two-year delay, who introduced me to one of the authors of the cover story that week in the magazine, about the disappeared in Argentina.

It turned out that the Times had been sitting on that story for more than a year. I almost became physically ill, fighting back the bile, thinking about how many thousands of people had been killed and tortured while the story was held in some kind of publishing purgatory, on the apparent political whim of the editor.

The telling of stories is a most human endeavor; our own stories are our most prized possessions. It creates a sense of connection and continuity in our lives.

The biggest consequence in the corporate takeover of the news industry is the demise of the local storytelling that knits together our past with our future.

BUENOS AIRES, Argentina – This is not a letter about health care. Or, perhaps, it is not much about health care.

Buenos Aires is one of great cities of the world, bubbling over with people and traffic, with layer upon layer of neighborhood and architecture, buildings and people crammed together and constantly reinvented and re-engineered for changing politics, technology and mores.

It feels like New York, London, Paris, Barcelona, Rome, Florence and Athens, similar in its perspective and its energy, different in small ways of its own.

Buenos Aires has more public art than New York. There aren’t hordes of tourists, the way there are in Paris, London and New York.

Buenos Aires has more flower shops than Rome. It has armed police wearing bulletproof vests on every street corner, like Athens. The people are white and European, with a tiny bit of mestizo inflection.

Buenos Aires doesn’t have the crowds of young people who congregate on the steps of big public buildings the way Florence does. It lacks the style, passion and aesthetic of Paris. Every block has a small, brightly lit cafe, were people meet for drinks and small plates of dinner, so every neighborhood looks like it lives in the world of Edward Hopper.

Life goes on. People live it. They meet for drinks after work. There are a few homeless people sleeping on the streets but nowhere near as many in any city in the U.S. Few beggars. There are only occasional sirens. No apparent distress.

A history lesson

We went the first day to Espacio Memoria Y Derechos Humanos, the old Naval Ex- Officer’s Club, a nondescript old mansion on the grounds of the Naval War College and Naval Engineers School, a campus of 20 or 30 building on the riverside.

It was here, in this old mansion, that 5,000 people were tortured and killed between 1976 and 1983, during the dictatorship of Jorge Rafeal Videla. Thirty thousand Argentines were killed during that period, at 600 other such sites across Argentina, tortured, murdered, drugged and their bodies dropped into the sea from helicopters. Women were raped and the children born as a result were stolen and given to families of their rapists to bring up, the mothers often murdered as soon as their children were delivered.

There was no foreign enemy. Just a period of foment, with intellectuals and revolutionaries on one side, and a military bureaucracy out of control on the other.

Those who disagreed; those who watched

The people who were tortured and killed weren’t foreign spies or the soldiers of invading Army. They were Argentines who disagreed – social activists, some of whom were armed revolutionaries, but most of the “disappeared” were just workers, trade unionists, students, teachers, artists, intellectuals, doctors and lawyers, nuns and priests – people who were evaporated because of what they thought and what they believed.

Some were disappeared because someone in the military didn’t like them; others because someone in the military wanted what they had – a house, or even a girlfriend. Many of the women who were pregnant were kept alive until their babies were delivered. Then those babies were given to military families to raise; the mothers were dropped into the sea. Disappeared. Injected with sodium pentothal and dropped still alive from helicopters into the ocean so their bodies would never be found.

Later, after it was over, there were a few arrests and a few trials and then a political deal which created and amnesty for the perpetrators, and then later, the opening of the files again, but no real accounting for the repression that convulsed this nation, which turned some Argentines against one another, while most watched silently and went about their business.

My own education

I was in medical school during those years, and spent two months in Scotland, learning to deliver babies in 1982. I stayed in hospital-owned housing in Glasgow. One of my suite mates was a gentle Argentine Jewish kidney specialist named Jose Zabloudosky.

Jose had arrived a week or two before me. His English was better than my Spanish, and we would laugh together about the crazy way they speak in Glasgow, and about how Jose’s English was peppered with Spanish pronunciation and Yiddish intonation, which made him say “Jail” when he meant the Ivy League university in New Haven.

Jose had arrived in Scotland after a sudden departure from Buenos Aires. He was an amateur photographer and had been walking on the riverside one Sunday, just taking pictures, when the men came in cars, put a hood on his head, and brought him to the building he had accidentally taken a picture of, which was the Ex-Officer’s Club.

Jose’s survival is a miracle: he was on his way to meet his sister, who had friends who had friends. When Jose didn’t appear at the appointed time, his sister made calls to people who made calls to other people, and somehow, miraculously, there was an arrangement.

Jose was put on the first available flight out of Argentina, which brought him to London, and then he found a place to work in Scotland for a few months while his life calmed down, a calming which meant a move to Israel, where he now lives and works.

He always said he was taking pictures of that building by accident, and I never had any reason to doubt him. But if he was taking photos of that building for another reason, if he was working with others to bring international attention to the disappeared, as I wondered then, he would be just as honorable in my eyes, and maybe even little bit of a hero, as I thought then and I think now.

Nondescript building

Jose never thought of himself as a hero, and always said he was taking those pictures by accident. Now I have been to the building, and know it is nondescript – nothing any amateur photographer would want to take a picture of on a Sunday afternoon.

Perhaps the true heroes are those who resist quietly, in the same way the true villains are those who accept oppression without complaint, who see and sense injustice but just go about their business and never say a word.

So this is about health care, after all. It is about workplaces. And, it is about politics. People in health care see the mess, and don’t say anything about it because they are afraid for their jobs and afraid to stand out.

People in workplaces act the same way, as if the democracy ended 30 years ago, and you do what your union or your company says without question, no matter how crazy it is.

People in politics are also afraid to speak up or vote wrong – everyone knows what the consequences are for voting against the leadership. We have evolved into a world in which it is no longer safe to disagree.

But, if we don’t speak up for the common good, then disasters like “the time of the Generals” can, will, and do happen. Every moment counts.

Dr. Michael Fine, the Senior Population Health and Clinical Officer at Blackstone Valley Community Health Care, is traveling in South America.