How to stop making children the detectors of toxic hazards

Pediatrician Dr. Mona Hanna Attisha shares the story of what happened in Flint, Mich., as part of a larger conflict about injustice and suppression of democracy

PROVIDENCE – Call it a crime story that is still unfolding, in Flint, Mich., in numerous cities across America, and here in Rhode Island. Children are being robbed of their future in broad daylight, in their homes and neighborhoods.

There is no safe level of lead in children, scientists and doctors agree. Lead is an irreversible neurotoxin; lead poisoning is a preventable childhood disease.

Even at very low levels, lead exposure in children can cause irreversible damage, including slowed growth and development, learning disabilities, behavioral problems and neurological damages, according to the most recent 2019 Rhode Island Kids Count Factbook. Children are most susceptible to the toxic effects of lead because they absorb lead more readily than adults.

In 2012, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lowered the threshold for which a child is deemed to have an elevated blood lead level to 5 parts per billion.

In Flint, Mich., in April of 2014, after state managers appointed to oversee the city finances decided, for “austerity” reasons, to switch the city’s drinking water source drawn from the Great Lakes to water from the local Flint River, the amount of lead levels found in tap water soared to hundreds and even to thousands of parts per billion, the highest found in a home being some 22,000 parts per billion.

The crisis redefined what it meant to be an at-risk child in Flint: a home for troubled children and foster kids, adjacent to the local hospital, was found to have had a lead level in their water of 5,000 parts per billion.

When General Motors discovered that the water was corroding engine parts at one of their factories in Flint, the company was allowed to switch back to water from the Great Lakes; but the residents of Flint were forced to drink the harmful water. One person from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency likened it to drinking water through a lead-painted straw.

Sharing the evidence

A public health crisis ensued, led by citizen scientists, angry residents, and a local pediatrician, Dr. Mona Hanna Attisha, who published scientific research documenting the evidence of childhood lead poisoning in Flint, only to have her data attacked by state officials, who called her an “unfortunate researcher.”

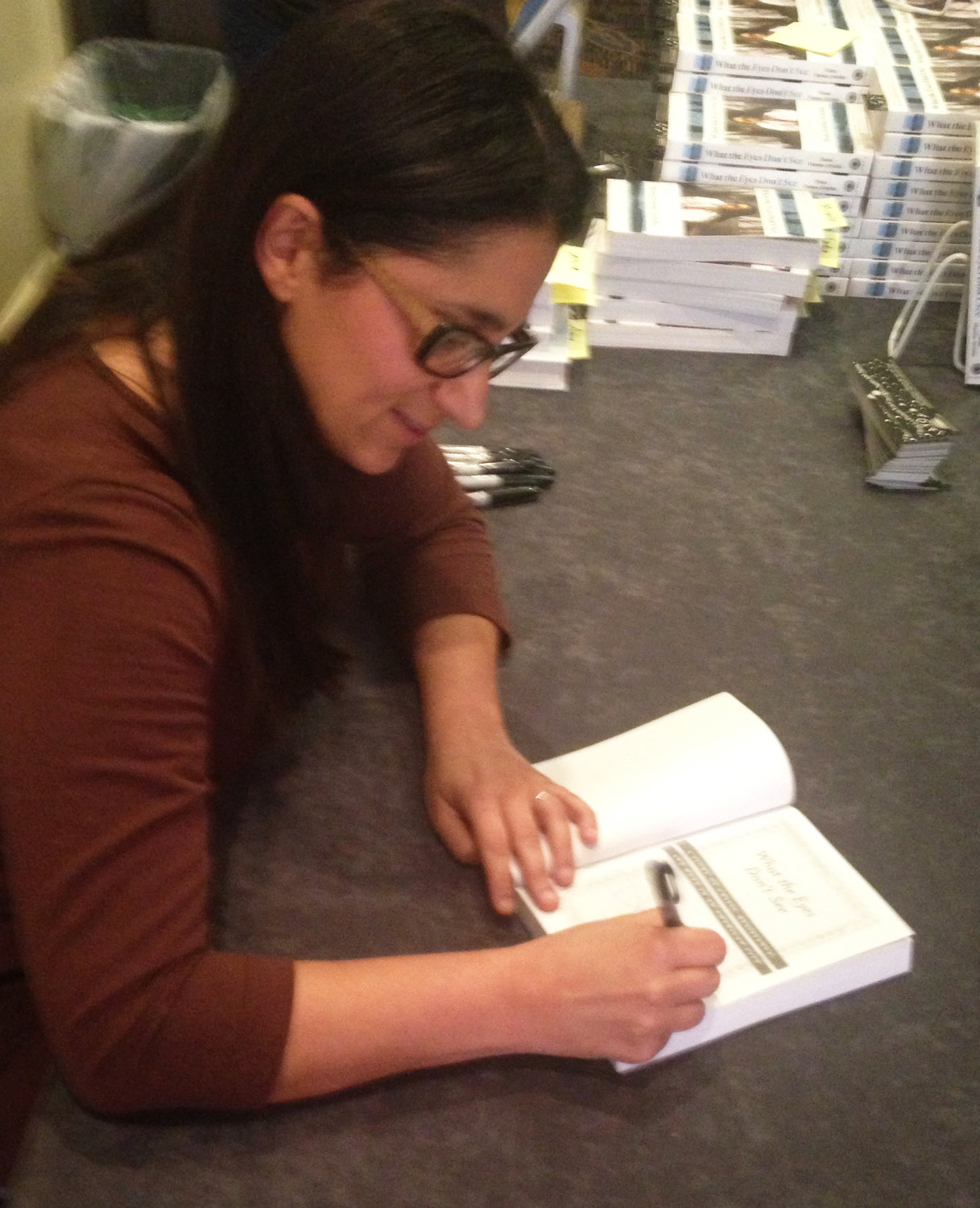

Dr. Mona, [as she is called by colleagues and patients], spoke last week in Rhode Island, as part of two public events promoting her book, What the Eyes Don’t See, the 2019 selection of Reading Across Rhode Island, a division of RI Center for the Book.

Her first talk, held on Thursday morning, April 11 at the Providence Marriott Downtown, drew a capacity crowd, and was followed by a book signing. The audience was filled to the brim with housing advocates, community activists, African American storytellers, public health students from Brown, and a few legislators, including state Rep. Rebecca Kislak.

Dr. Mona began her talk by reading an excerpt from her book, in which she dismisses the concerns from a young mother with two children, during a clinic appointment for her four-month old, about the water quality in Flint. The mother, who was going back to her job as a waitress, had made the decision to stop breastfeeding, because there was no place to pump at work. Instead, she would be using a dry formula and mixing it with water.

Dr. Mona assured her not to worry, and not to waste resources on buying bottled water; the pediatrician shared the story in recognition of her own unknowing participation in the coming public health crisis.

“And I said: ‘Don’t waste your money on bottled water,’ nodding at [the mother] with calm reassurance, the way that doctors are taught. ‘They say that it’s fine to drink.’ I gave the mother another nod. ‘The tap water is just fine.’”

The reality was, Flint’s tap water was not just fine.

A history lesson

Dr. Mona also provided the audience with a brief history lesson about Flint: it served as the home of where General Motors was born; in the 1930s, it was also the place where the union, the United Auto Workers was forged, in what was later called “the grand bargain,” helping to create a thriving middle class all across the nation.

“I want to digress into a little history,” Dr. Mona explained, “because we walk over complex systems every day. We walk over history every day; we do a really good job of closing our eyes to anything that’s too complicated and too dark to process.”

But history, she continued, is important, “because if we want to solve our complex social and public health problems moving forward, we have to start by looking back.”

Yes, Flint was the birthplace of General Motors, Dr. Mona said, but more importantly, “Flint was the birthplace of unions, of resistance and disobedience and contracts,” demanding living wages and occupational health and safety.”

As late as the 1970s, Flint has the highest rate of per capita wealth in the nation. Since then, reflective of the economic divisions in America, Flint has sunk into a city engulfed in poverty and violence. Dr. Mona said that before the water crisis, she often treated children for lead poisoning who had retained bullets in their bodies from being shot.

The story of what happened to Flint, she said, “is the story of what happens when the very people responsible for keeping us safe and healthy care more about money and power than they do about us, and most importantly, our children.”

One of the reasons, Dr. Mona continued, explaining why she wrote the book, “is to share that the story of Flint is not isolated. It is a story that speaks to the deeper crises that we are in as a nation – the disintegration of critical infrastructure, environmental injustice that disproportionately affects the poor and minorities, the disrespect for science and facts, and the assault on our children, and most of all, a disregard, a blindness, for people and places and problems that we choose not to see.

Despite all the “badness” in the story, Dr. Mona also called what happened in Flint a story of hope and resilience. “Yes, it is a story of crime and absolute indifference to some of the most vulnerable people in our country. But it is also the story of how everyday people – moms and pastors and activists and scientists and journalists and doctors, said: We’ve had enough, and took action on behalf of our children. So, that is the story that we all need right now, because it is the story of resistance and hope for our children.”

Public health interventions

In the face of the public health crisis, one of the public health interventions that was adopted by Dr. Mona and her clinic was to create a nutrition prescription program, allowing every patient to purchase fresh fruits and veggies at the food coop located downstairs from the clinic. Flint, Dr. Mona explained, does not have a full service grocery store, and the ability to find and to purchase healthy produce such as kale would be an impossible task otherwise.

The nutrition prescription program developed by Dr. Mona and her pediatric clinic so impressed Michigan Sen. Debbie Stabinow that she wrote a provision that was included in the recent farm bill passed by Congress and signed into law, according to Dr. Mona.

Lessons learned

Dr. Mona stressed that “the burden of lead does not fall equally on our nation’s children.” To make a difference in the story, she realized, she would need science, she would need data, she would need facts. [In her book, Dr. Mona documents the key role that the health IT system built by Epic played in crunching the numbers for her research documenting the lead poisoning of Flint’s children; it could provide a new kind of marketing campaign for the importance of health IT systems in protecting the public’s health.]

But the importance of the numbers, Dr. Mona said, was the realization that each number documenting lead poisoning represented a child.

What the legislators don’t see

As ConvergenceRI left the gathering, with Dr. Mona busy signing copies of her book, he asked a community activist: What would happen if the Speaker of the House and the Senate President were presented with their own copy of What the Eyes Don’t See? Why not give a copy to every single member of the R.I. General Assembly?

As a kind of community organizing tactic, it seemed like the kind of initiative that might capture the attention of Rhode Island’s legislative leaders, who should not be so stiff-necked about their own inability not to see – or read.

The evidence of Rhode Island’s continued complicity in the ongoing crimes against the state’s children, robbing them of their future, is laid out on Page 76 of the 2019 Rhode Island Kids Count Factbook.

• In 2018, some 635 children out of the 23,031 children under age six who were screened had confirmed elevated blood lead levels. Children living in the state’s four core cities were four times more likely as children in the remainder of the state to have confirmed elevated blood lead levels.

• Exposure to lead had been shown to negatively impact academic performance in early childhood, and Rhode Island children with a history of lead exposure, even at low levels, have been shown to have decreased reading readiness in kindergarten entry and diminished reading and math proficiency in third grade.

• Children with lead exposure are also at increased risk for absenteeism, grade repetition, and special education services.

While the total number of children under age six who were screened and identified as having elevated blood levels in 2018, 635, may seem like a small number to some, to put it in perspective, in the last three years, the number of people who died in drug overdoses were 336 in 2016, 324 in 2017, and 314 in 2018.

Here’s a suggestion: instead of making a campaign donation to legislative candidates running for the R.I. General Assembly, send them a copy of What the Eyes Don’t See.