Navigating through the fog of wealth

A summit on preventing childhood lead poisoning connects to the growing problems of affordable housing

We need to start asking questions about what it means to be part of an engaged community, in a place-based neighborhood, where investments are made based upon the risks identified,

PART Two

PROVIDENCE – In the midst of an affordable housing crisis, where the average income earner can’t afford a home anywhere in Rhode Island, where the average renter can afford rent in only one town – Burrillville, where there is a shortage of some 24,000 low-income housing units, and minorities and low-income children are disproportionately affected, families need safe and affordable places to live.

Those were the messages delivered at the 2022 Summit To End Childhood Lead Poisoning, held on Friday, Sept. 30, at Rhode Island College, sponsored by the R.I. Department of Health, in partnership with the Rhode Island Office of the Attorney General and the Childhood Lead Action Project, the leading statewide community agency seeking to eliminate lead poisoning in children.

Childhood lead poisoning is an entirely preventable disease. Despite the state having good laws on the books, a state health department invested in conducting aggressive inspections and testing children for lead poisoning, as well as an aggressive Attorney General willing to take negligent landlords to court and municipalities ramping up enforcing code enforcement activities, it still requires vigilance:

• In 2021, 432 children were newly lead poisoned in Rhode Island.

• Rhode Island has the second highest rate of children under the age of six with severe lead poisoning in New England.

• Lead poisoning affects 1 out of 14 rising Rhode Island kindergarten students.

• Lead exposure is caused in large part by contact with lead paint and dust in homes built before 1978. With the removal of lead hazards from a child’s home, lead poisoning is 100 percent preventable.

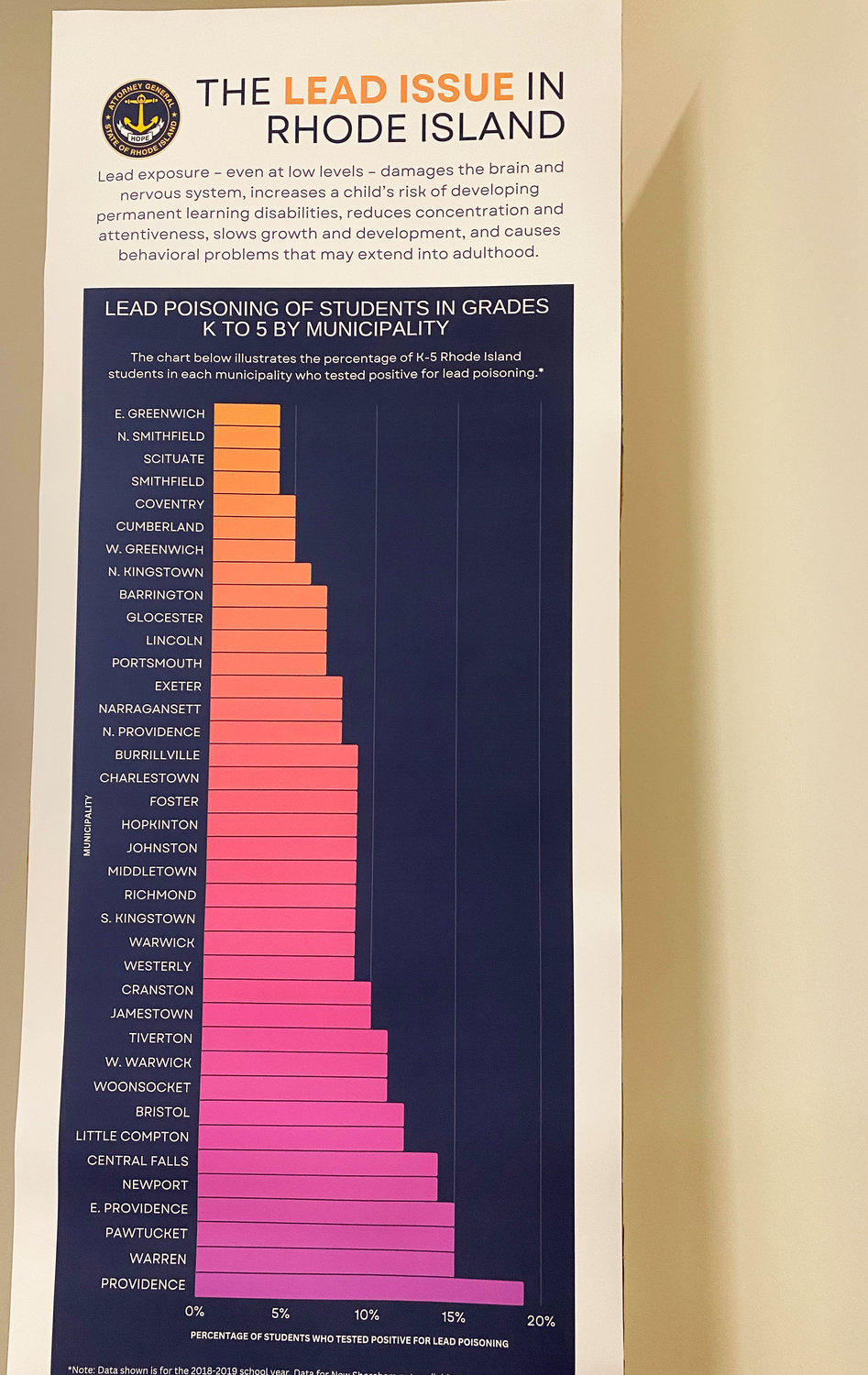

Translated, older housing stock in urban core cities make childhood lead poisoning an affliction that is tied to poverty, although lead poisoning of students in Grades K to 5 exists in every municipality in Rhode Island.

Across the great wealth divide

What the recent dust-up between Gov. McKee and candidate Kalus over primary and secondary residences obscured were the ongoing political and economic challenges facing the next Governor: the growing number of Rhode Islanders who lack a roof over their heads.

Translated, the state's affordable housing controversy takes on new relevance, in ConvergenceRI’s opinion, when contrasted with those Rhode Islanders who don’t have a roof over their heads. Whether you call them “unhoused” or “homeless,” the tragic reality is that too many Rhode Islanders need shelter from the storm, at a time when the weather is turning colder.

On Friday afternoon, Sept. 30, Gov. McKee issued a news release touting the awards of $3.5 million to create a total 231 additional shelter beds. The investments included:

• Amos House Family Shelter [Pawtucket] $1,338,655

• Blackstone Valley Advocacy Center [Central Falls] $966,870

• Catholic Social Services of Rhode Island [Providence] $20,000

• Sojourner House [Providence] $180,899

• Thrive Behavior Health [West Warwick] $827,103

• Westerly Area Rest Meals (WARM) Center (Westerly): $220,103

“Having worked closely with the providers and Gov. McKee and Secretary Saal, I am encouraged by all who have worked diligently to get to this first step to provide shelter beds for the growing number of unhoused individuals and families in the state,” said Neil Steinberg, president and CEO of the Rhode Island Foundation, in the news release accompanying the announcement of $3.5 million in grants to create additional shelter beds. Steinberg continued: “The Governor’s commitment to quickly continuing this effort will enable the providers to manage shelters for all that need it as the cold weather approaches.”

[Editor’s Note: Not everyone was as pleased as Steinberg with the outcome. On Monday morning, Oct. 3, at 10 a.m.,a rally will be held in Burnside Park, with advocates demanding that Rhode Island “must declare a state of emergency to ensure shelter for all Rhode Islanders. The slogan attached to the rally poster says: “House the Homeless or get out of our House,” with a image of the State House.”]

The announcement followed weeks of tense negotiations between Gov. McKee, Neil Steinberg, president and CEO of the Rhode Island Foundation, Eric Hirsch, Ph.D., Interim Director, Black Studies Program at Providence College, Josh Saal, the Rhode Island Secretary of Housing, and leaders from nine community agencies and providers. The negotiations culminated in a Wednesday, Sept. 21, session at the State House.

Difficulty in finding common ground?

The negotiations between the Governor and the community providers, Housing Secretary Saal and Steinberg were kept on the hush-hush. When ConvergenceRI asked Matt Sheaff, senior communications advisor to Gov. McKee, on Tuesday, Sept. 20: “Is there a meeting this week with Steinberg et al to talk about a homelessness plan?” Sheaff responded by saying: “Our team has regular meetings various stakeholders regarding housing and homelessness issues.”

The community providers had prepared a plan of action, which they wanted to present to the Governor and to Saal. One participant involved in the negotiations shared the context around the dialogue:

• “The recent message from the Governor, and even from Josh Saal, has been to ask what the homeless service providers have done with the money they already have been granted. There are two problems with this. It ignores the dramatic increase in the number of people becoming homeless, particularly those who have been forced outside, and it ignores the failure of the state to help with siting of shelter beds, both in buildings and rapidly deployable structures.”

Another participant, in preparation for the Wednesday, Sept. 21, meeting with the Governor, offered suggestions about the kind of information that might prove helpful:

• “It would be great if each of you could document what you have done with the existing funding, perhaps briefly listing two projects. We can provide this list at the meeting. We will certainly document the increasing needs for funds but also the need for help overcoming NIMBY zoning and regulatory barriers.”

The importance of creating a “State of Emergency” was emphasized by one participant:

• “I still feel the State of Emergency is needed to facilitate siting. We also need to document the need for the additional housing problem solving/diversion funding. That has been the most effective way we have assisted people in getting permanent housing.”

Another participant weighed in about the frustrations of having to prove the value of the work being done.

• “I do realize that we need to be accountable for the resources that we are entrusted with to care for our clients. That being said, this question ‘I already gave you money, why do you need more?’ demonstrates an appalling lack of understanding of the crisis we are dealing with.”

The participant continued, voicing anger about the apparent “disconnect” regarding how the outcomes of the work were being measured:

• “On a global level, we have the data to support the number of people served via both winter shelter, traditional shelters and non-congregate shelter. We know how many were housed. How many individual/families were diverted from homelessness.”

The participant then talked about the value of the work, in human terms:

• “That we kept people from dying or suffering from being unhoused is an accomplishment in and of itself. We fed them, clothed them, connected them with behavioral healthcare providers, connected them with primary care, obtained IDs/social security cards. Because of our efforts, they are alive. We have more people who reduced their substance use and/or illegal activity, had chronic health issues treated, found jobs, started education programs, reunited with their children or avoided child welfare programs. We gave people hope.”