Screening and treating maternal depression in RI

New issue brief by Rhode Island Kids Count identifies the issues and recommended strategies, but the question remains how the solutions can involve community-based initiatives

There are political consequences to not making decisions and kicking the can further down the road.

The progressive caucus, led by Rep. Aaron Regunberg and others, is providing a vocal presence at the State House, challenging the status quo. One sign of the growing influence of the progressive caucus is the recent attack by Mike Stenhouse in an op-ed in The Providence Journal. Another sign of its growing influence was the denial by lawyer Eva Mancuso, in a heated dialogue with ConvergenceRI on “A Lively Experiment,” that there was even such a thing as a progressive legislative caucus.

Watch out, Rhode Island, there is a new political ground game afoot.

PROVIDENCE – In a world divided by partisan politics and separated by huge ideological chasms in policy, the presentation on Jan. 22 by Rhode Island Kids Count of its latest issue brief, “Maternal Depression in Rhode Island: Two Generations at Risk,” reflected a genuine consensus by health care and social service professionals and children’s advocates, both on identifying the problem and the pursuit of recommendations and interventions to address the problem.

The facts are clear: in Rhode Island between 2012 and 2015, some 18 percent of mothers reported that they were diagnosed with depression during and/or after pregnancy, with a higher prevalence among mothers in lower-income families, racial minorities, mothers under age 20, and mothers without a high-school diploma.

So, too, are the consequences of maternal depression on children and mothers. According to the brief, maternal depression can:

• Interfere with a person’s ability to develop and sustain healthy relationships and to have positive interactions with others.

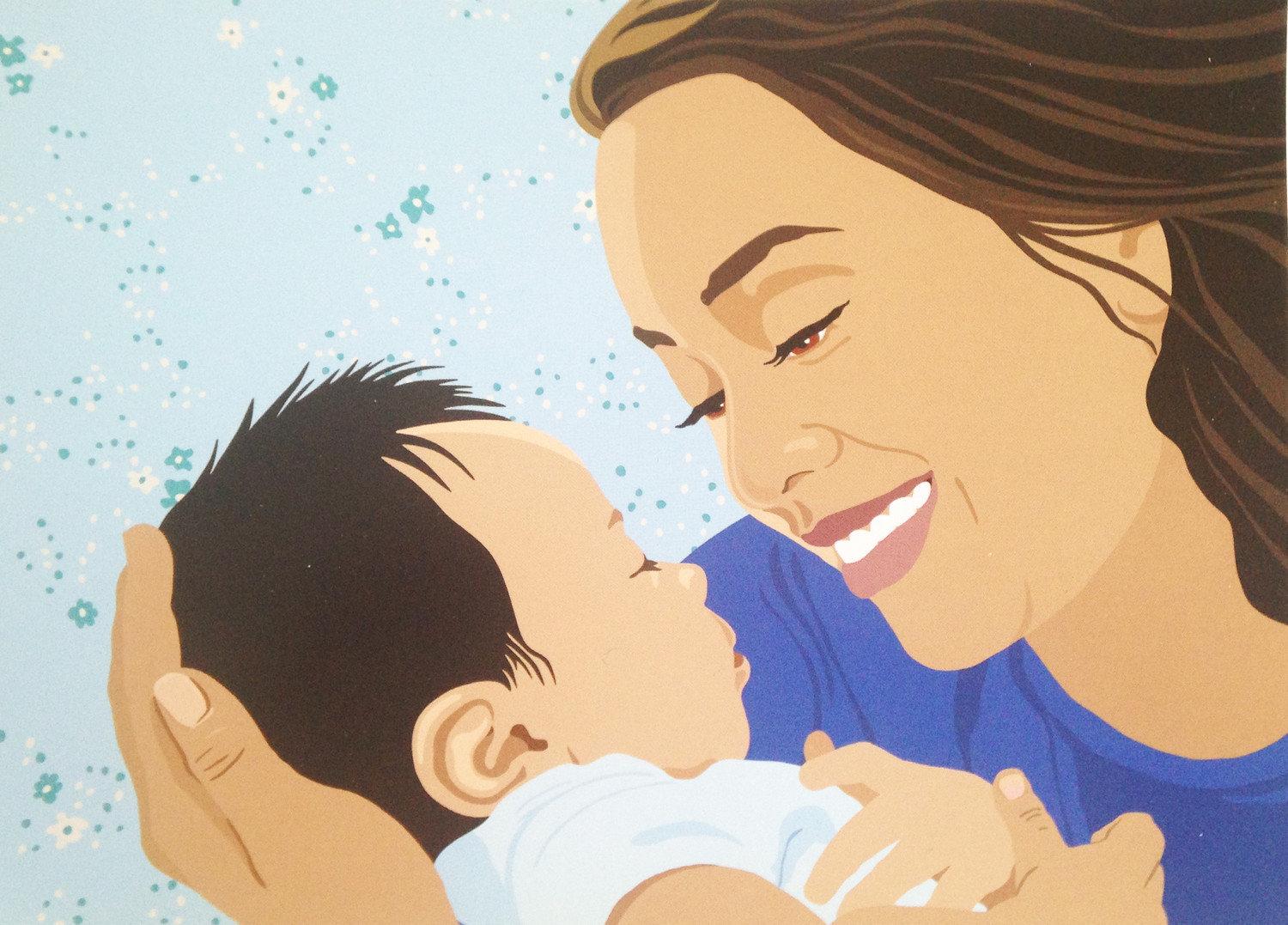

• Disrupt healthy brain development in infants, which requires a “serve and return” pattern of interactions with parents and other caregivers, noticing and responding to the baby’s needs and signals. [To make that point at the briefing, Leanne Barrett of Rhode Island Kids Count played a short video capturing what happens between a mother and her child when the mother is attentive and when she is not.]

• Lead to toxic stress in babies who do not experience positive, consistent interactions with their parents and other caregivers.

• Be a contributing factor associated with chronic disease such as obesity, smoking and substance abuse.

Screening for maternal depression

As the brief made clear, maternal depression often goes undetected, undiagnosed and untreated in Rhode Island.

An effort is underway in Rhode Island to improve screening, through both the short-term First Connections program of family home visiting and longer-term programs such as Nurse Family Partnerships, Healthy Families America and Parents as Teachers.

• In 2017, there were seven pediatric practices in Rhode Island participating in a learning collaborative focused on postpartum depression screening through PCMH-Kids.

Treatment options

The Rhode Island Kids Count brief identified a number of treatment options, while acknowledging that there was a significant gap between those mothers diagnosed with depression during pregnancy and those receiving treatment. Between 2012 and 2015 in Rhode Island, some 71 percent diagnosed with depression during pregnancy received treatment while some 29 percent did not.

The treatment options include:

• Psychotherapy, medication, mother-infant psychotherapy and peer support.

• The Day Hospital at Women & Infants Hospital, which was launched in 2000, provides pregnant women and new mothers diagnosed with depression in a nurturing setting, in which babies remain with their mothers.

A significant barrier to diagnosing and treating maternal depression has been the income barriers imposed by health insurance regulations. While 97.8 percent of Rhode Island’s children have health insurance coverage, some women who were eligible during pregnancy can lose their eligibility for coverage at 60 days postpartum.

To help remedy this, the Rhode Island Medicaid office is considering moving ahead with a program to replicate a New York State program, called the “First 1,000 Days of RIte Care initiative, in order to improve health and developmental outcomes for infants and toddlers in low-income families.

Commentary and discussion

Dr. Nicole Alexander-Scott, the director of the R.I. Department of Health, praised the team effort behind the issue brief. For her, the takeaway from looking at the story line is how the data showed risk factors that correlated with health disparities in communities.

The data, Alexander-Scott continued, should “inform how we respond,” stressing community-based interventions being developed as part of the Health Equity Zone initiatives in 10 Rhode Island communities. “We need to be able to offer a community-based perspective so we can meet people where they live,” she said. “If we don’t, there are generational consequences.”

Patrick Tigue, the director of the state’s Medicaid office, talked about the need to recognize and reduce the risk factors in the social determinants of health, including housing and economic security.

Margaret Howard, the director of the Day Hospital at Women & Infants, said that screening and identifying the risk of maternal depression was not so great if we don’t have treatment options and interventions available.

In turn, providing treatments options and interventions offers the chance to put a halt to the generational transmission of depression, Howard said.

Dr. Patricia Flanagan, a pediatrician who is one of the co-founders of PCMH Kids and director of the Teens with Tots program at Hasbro Children’s Hospital, is now involved with expanding maternal screening for depression involving seven practices and 88 pediatricians.

She identified a continuing barrier that families that are screened still have difficulties in connecting with treatment providers.

Barriers

Another participant in the roundtable discussion raised the issue of the apparent insurance barrier that, after 12 treatments under behavioral health coverage, there was a need to seek reauthorization of treatments, often leading to a drop-off in participation by patients.

Lynn Blanchette, associate dean at the Rhode Island College School of Nursing, raised the issue of workforce development and coordination with home visitation, including better deployment of nursing students who have clinical training in identifying and screening for maternal depression.

Susan Orban, director of Health and Wellness at South County Health and coordinator of the Washington County Coalition for Children, spoke about the difficulties of accessing treatment in rural communities outside of Providence.

Two other participants in the roundtable brought up questions about the reliability of the data related to cultural and economic differences: in the Latino community, depression was not something that was willingly acknowledged by mothers; and for many mothers in disadvantaged settings, admitting to depression came with the worry that DCYF could come and remove their children from the home.

Time ran out for further discussion at the roundtable, just as the conversation began to get more involved. Is there a time and a place for a continuing dialogue around maternal depression in Rhode Island?