Still working on the railroad

The history of how a dedicated group of advocates transformed abandoned railroad lines into an active network of transportation

Under the program, coordinated by Sandy Playa, “Island Rides “ has a fleet of electric vehicles driven by an eclectic group of volunteers, offering rides from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m., seven days a week. The drivers take residents to markets, medical appointments, Senior Center lunches, ferries, classes, banks, pharmacy, auto repair shops, and to visit friends, according to a story in The Islands’ Sounder.

They also provide weekly deliveries from the Food Bank for islanders who are unable to leave their homes. The group has two sayings: “Driven by Volunteers, Powered by Electricity” and “Donations are Accepted – but not Expected.”

One of the most recent unexpected donations was the keys and title to a 2014 BMW 13 EV by resident Sarah Rehder.

Imagine if such a program could be developed in Rhode Island, with donations from car dealers and residents, putting together a network of community volunteers, supported by donations from health insurers. Food for thought.

PART One

Editor’s Note: When the history of the environmental movement in America is written, there will be no doubt all kinds of scholarly efforts to try to connect what happened on Earth Day, the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1972, and the waves of citizen actions and protests to seize the day around urgent environmental crises.

What was unique about Earth Day was galvanizing the concept of citizens taking charge of their own lives to protect Mother Earth, creating an agenda of community-led interventions.

From the launch of the Superfund legislation in 1980, spurred on by housewife Lois Gibbs in Buffalo, N.Y., to the No Nukes movement challenging the nuclear industry by farmers in Montague, Mass., from the efforts to create “bottle bill” regulations to control the epidemic of trash to efforts of legal advocacy to ban dangerous pesticides such as DDT, from the efforts to create better regulation of the utility industry to the adoption of modern-day public power authorities and construction of behind-the-meter renewable energy, what often gets left out of the story is how dedicated activists, often responding to the economic catastrophes created by corporate malfeasance, did their best to rescue the planet.

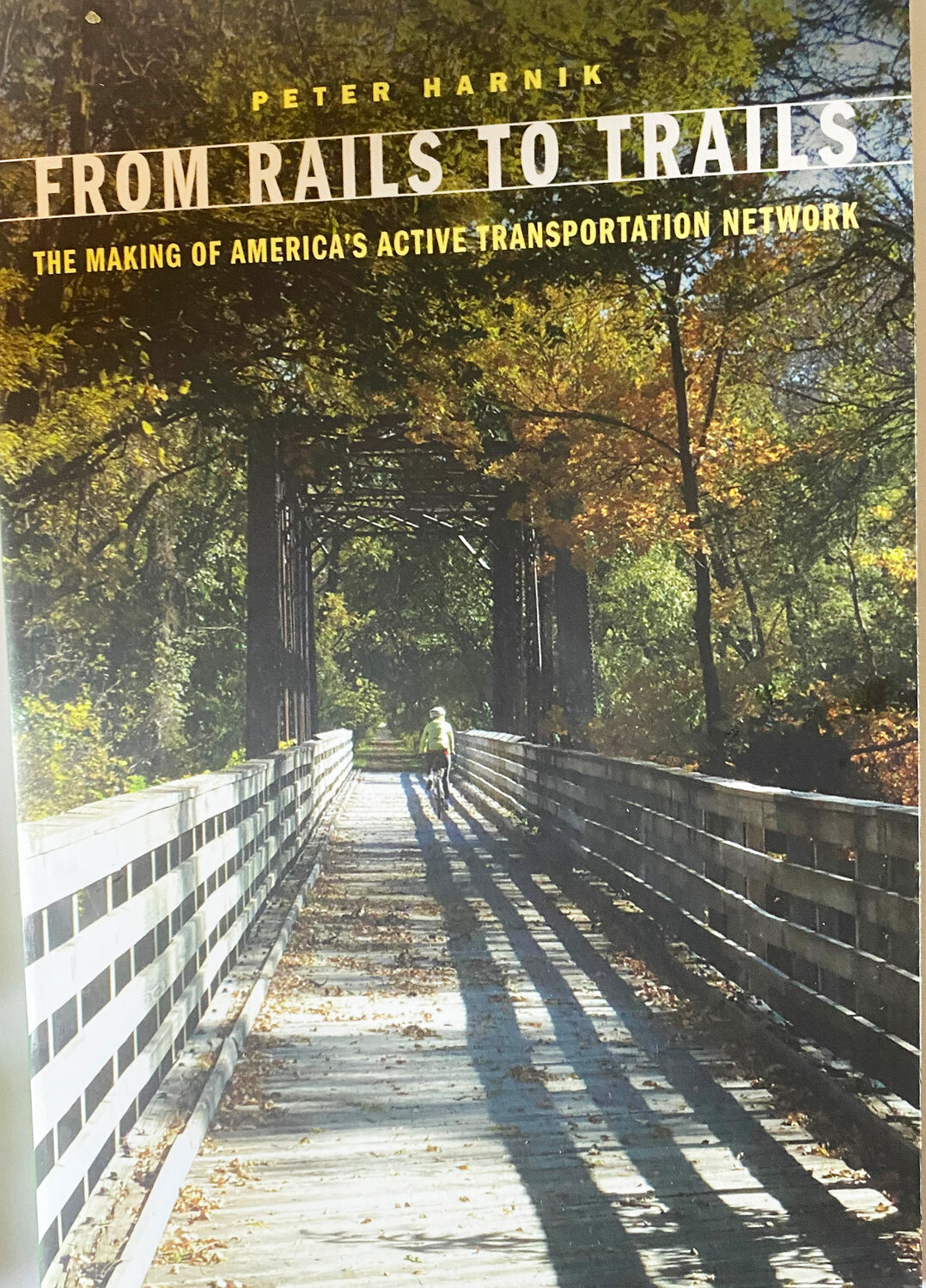

Peter Harnik, co-founder of the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy and founder of the Center for City Park Excellence at the Trust for Public Land, has documented the successful efforts to take abandoned railroad lines across the United States and turn them into hiking and biking trails. He has written a definitive book, “Rails To Trails: The making of America’s active transportation network,” which retells the story of these efforts.

What follows is an excerpt from his book, published by the University of Nebraska Press. In the excerpt, Harnik details the economic forces at work behind the abandonment of roughly 120,000 miles of rail lines. Thanks to Harnik and his cohorts, many of those abandoned railways have been given a second life, as bike trails, walking paths and an active transportation network.

CHAPTER FOUR: Dark Days and a Seismic Shift

“I want to go to Chicago in the worst way.”

“You want to go to Chicago in the worst way?”

“Yes.”

“Take the Erie!”

IT WASN’T SUPPOSED TO BE like that cynical joke. As World War Two ended, the railroads were expected to flourish. There was a brief, fleeting moment when U.S. transportation policy could have fused suburban bicycling and intercity railroading into a seamless, perfect fit.

After all, the convenient, nimble, space-conserving bike is ideal for covering the “first mile” from home or the “last mile” to work, while the muscular, efficient high-speed train is perfect for moving multitudes the longer distance between.

For decades, consummating this theoretical union had been thwarted by impediments – company takeovers, un-cyclable roads, railroad nationalization during World War I, economic collapses, and then, during World War II, a vastly overcrowded track network.

Finally, after the war, it seemed that the rainbow of this marriage might be visible at the end of the highway.

But it was not to be. Despite the elegance of the bike-train-bike minuet, most Americans felt the whole rigamarole could be eliminated by the effortless, all-weather, one-step solution of buying an automobile. Which they did by the millions.

Driving in the early years felt like a nearly free lunch; only in the 1960s would severe societal impacts begin showing up – clogged highways, smoggy air, road rage, the distortion of urban life as buildings were torn down for gargantuan parking lots and high-rise garages, and a massive collective expense.

This was America’s second Great Disruption [the first one, 100 years earler, being due to the railroads].

The automobile, combined with each state’s urban renewal scheme, was redesigning virtually every facet of our culture. And, with almost no warning, both trains and bikes found themselves brusquely bulldozed aside.

Bikes went first

Bikes, already on shaky ground, went first. They had taken a big hit in the early years of the twentieth century, and despite small waves of resurgence from technical improvements, health claims, or Hollywood glamour, the overall effect was like the occasional hopeful ripple in a rapidly receding tide.

The Depression led a few people to pedal rather than drive, but, of course, those were people far down the social order who didn’t set trends.

The economic earthquake of World War II democratized things a bit and led to a short bicycling rebirth when Detroit was ordered to make military tanks rather than autos and when gasoline and tires were severely rationed.

In fact, the bicycle proved itself to be an outstanding emergency vehicle in scores of applications, both on the road and within sprawling production facilities. But it didn’t last.

Those soldiers embracing their girlfriends in Times Square on VJ Day might well have been kissing their bikes good-bye. With the rise of auto traffic, on-street cycling came almost to an end, while off-street trails were essentially non-existent. The adult bicyclist came close to obliteration.

Railroad carnage

For railroads the carnage was more surprising, more tortured, and profoundly ironic, since the 1950s could have been the decade when the sector’s many battered stars would finally align.

Here was a business that had dominated the industrial, economic, and cultural life of the United States for nearly a century. It had carried settlers west. It had survived price wars as vicious as the one in 1887 between the Southern Pacific Railroad and the Santa Fe Railway, where a ticket from Chicago to Los Angeles could be had for $1.

It had transported millions of soldiers free of charge as repayment for lands given to railroads by the federal government. It had been nationalized during World War I and re-privatized immediately after.

It had struggled through the Depression with catastrophic drop-offs in shipping, travel, and revenue, and then, during World War II, turned around to transport unprecedented billions of tons of war materials plus hundreds of millions of soldiers and civilians in outmoded equipment on tracks that had been under-maintained for years. Despite all the glories of song and film, railroading had suffered and barely survived.

Industry optimists predicted a postwar corporate resurrection that would be led by the diesel-electric locomotive, the powerful new technology that simplified railroad operations and greatly increased the ability to haul long trains and heavy loads.

With diesels, the requirement for coal-shoveling firemen or for helper engines at steep grades was cut, and there was no need at all to stop at water tanks for refilling.

Enthusiastically, the companies scrapped tens of thousands of hulking old steam engines, switched to diesel, and began pouring investment into all facets of their physical plants, including lightweight passenger trains, welded rail tracks, and safer crossings.

When the guests didn’t show up

The table was set, but the guests didn’t show. Many of the invitees were waylaid by shiny new government-funded highways and airports. Shippers were increasingly choosing trucks, short-distance passengers were using cars, and long-distance travelers were rapidly shifting to airplanes [if they had money] or to intercity buses [if they didn’t].

The U.S Post Office Department shocked the industry in 1967 by ending the fat railway post office cars that had financially propped up the long-distance passenger trains; mail thenceforth went by truck, airplane, or freight rail.

Historians have long debated the role of the federal government in the slow-motion disaster. Without doubt, massive federal subsidies for the competitive modes of highways, waterways, ports, and airports served as a weighty finger on the other side of the balance, proving nearly ruinous to the private rail enterprise.

Moreover, a fairly consistent string of rulings by the Interstate Commerce Commission in favor of shippers and small towns forced the railroads to continue spending millions of dollars maintaining and operating unprofitable routes.

On the other hand, the industry’s long and often sordid history of rate manipulation, stock fraud, town and shipper intimidation, political machination, and other noxious tactics had left a residue of bitterness toward the business that may well have fostered enthusiasm for alternatives.

Deterioration in passenger service

The deterioration in passenger service, both long distance and commuter, became obvious to the general public, and it played into the vicious cycle of auto buying, road building, more auto buying, and train decline.

Interestingly, that warning bell didn’t overly alarm the rail companies [other than at New York’s virtually passenger-only Long Island Rail Road]. Insiders well knew that passenger service was a problematic, low-profit, and a thankless subspecies of the business that was kept alive mostly through the mandates of regulators and politicians.

The more people shifted to cares and buses, the railroads thought, the more they would be able to focus on their freight-hauling strengths and compete with trucks, boats and cargo planes. They were wrong. All the railroads struggled, and some didn’t even come close to making it.

The first company to abandon its entire system, in 1957, was the hapless 541-mile New York, Ontario & Western Railway. Next, three years later, was the Lehigh & New England, 177 miles. The dominoes were teetering.

Mergers and acquistions

Scrambling to avoid liquidation, most companies began to negotiate mergers. The combinations were very big news, and for a while, they gave the impression that smaller regional carriers were becoming massive nationwide players.

Between 1957 and 1968, for instance, the modest Chicago & North Western Railroad [C&NW], under the aggressive leadership of Ben Heineman, gobbled up both feeder lines and side-by-side competitors.

Among these were the Chicago, St. Paul, Minneapolis & Omaha Railroad, the Litchfield & Madison Railroad, Minneapolis & St. Louis Railroad, the Chicago Great Western Railroad, the Des Moines & Central Iowa Railroad, and the Fort Dodge, Des Moines & Southern Railroad.

These were smaller systems, but Heineman came close to also acquiring the huge Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Specific Railroad and the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad.

C&NW would have become a 30,000-mile behemoth, even though it was so financially fragile that it soon thereafter sold itself to its workers and then was later taken over by the Union Pacific Railroad.

In the East

It also happened in the East. The Chesapeake & Ohio swallowed the Pere Marquette in 1947 and then, 15 years later, did the inconceivable by absorbing the venerable Baltimore & Ohio, eventually eliminating its famous Capitol dome logo.

Changing its name to the Chessie System, the conglomerate next picked up the Western Maryland Railway in 1968 and the Seaboard Coast Line Railroad and Louisville & Nashville Railroad in 1980, whereupon its name changed once more, to the sterile and anonymous CSX Corporation [C for Chessie, S for Seaboard, and – I’m guessing – X for some undefined ominous speculation for what the future might hold.]

In the West

And, in the West. In 1970 four of the great names in northwest railroading – Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad, Great Northern Railway, Northern Pacific Railroad, and Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railroad – combined into the huge Burlington Northern system. [The other famous northwestern line, the Milwaukee Road, which was left out of the merger, went into bankruptcy seven years later, and became the source of the single longest rail abandonment ever, from eastern Montana almost to the Pacific Ocean.]

Most catastrophic merger

The grandest and most catastrophic merger took place in 1967, following 10 years of negotiations – the unification of archrivals Pennsylvania Railroad and New York Central [plus the frail, commuter-heavy New York, New Haven & Hartford] into the Penn Central. On paper it looked like the mightiest railroad of all time, representing well over a hundred years of unparalleled railroad leadership, but after only three years of failing to marry two clashing cultures and losing $1 million a day, it collapsed into the largest corporate bankruptcy to that point in American history.

The mergers were touted as cost-cutting victories and administrative streamlining breakthroughs, but they were actually corporate restructurings heavy with worker layoffs, union setbacks, and small town debacles.

It was the seismic, painful redesign of America’s largest industry from a “serve everyone with everything they need over every distance” model to a limited framework that focused on the steady, long-distance movement of large-volume, lower-value commodities like coal, gravel, grain, oil, and lumber. Within the merged entities, schedules were reduced, maintenance slashed, speeds cut, services eliminated, and, of course, duplicative track scrutinized.

Famous passenger trains came to an end – the Milwaukee’s Olympian Hiawatha between Chicago and Seattle in 1961; the New Haven’s Cape Codder between New York and Hyannis in 1964; the Lackawanna’s Phoebe Snow through the cleaner burning coal region between Hoboken, New Jersey, and Buffalo [with its advertising jingle, “My gown stays white/From morn to night/Upon the road of anthracite”] in 1966; the New York Central’s Twentieth Century Limited between New York and Chicago in 1967; and the gleaming, stainless steel, three-railroad California Zephyr vista-dome streamliner between Chicago and Oakland, California, in 1970

The rise of Amtrak

It was the loss of the Zephyr that accelerated the formation of Amtrak, the federally sponsored skeletal national intercity rail passenger system. But while [Amtrak] saved some trains at its start-up on May 1, 1971, its creation came at the price of many dozens of others that were discontinued, taking with them famous names and long-standing traditions – Norfolk & Western’s Wabash Cannonball from Detroit to St. Louis, the B&O’s National Limited from St. Louis to Washington; and the Union Pacific’s combined City of Los Angeles/City of San Francisco/City of Denver/City of Portland.

Then the freight routes themselves started to falter. The Erie-Lackawanna ended its route across lower New York State after damage from Hurricane Agnes in 1972. The Lehigh & Hudson stopped all service after a fire knocked out the Poughkeepsie Bridge in 1974.

Snoqualmie Pass in Washington was closed in 1975, and the rest of the long Milwaukee Road corridor across Montana and the Rockies was lost in 1977. A few years later the Denver & Rio Grande Western shut down its route through the Royal Gorge and over the Tennessee Pass in southern Colorado. Hardest hit were states in the Northeast, Upper Midwest, and Great Plains, but even economically growing stats like Texas, Florida, Georgia, and Tennessee saw significant reductions in mileage.

The public cried out in anger and confusion. Commuters seethed at the decline in service. Shippers lamented lost markets. Old-timers reminisced about past glory days of dressing up for the ride to the big city. Historians recalled the excitement of the massive engines’ smoke plumes and steam. Children mourned the death of the caboose. Environmental scientists deplored the loss of the nation’s second most energy-efficient transportation technology [after the bicycle].

In Part Two, to be featured in a later edition of ConvergenceRI, in an excerpt from the chapter, “The Movement Gels,” Harnik shares how the rails-to-trails movement gained traction.