The epic tale of Child Opportunity Zones in Rhode Island

More than two decades after the initiative was launched in 1994, some COZs are thriving, some have disappeared, but story remains mostly untold until now

When it comes to public education in the U.S., there is also a seemingly impenetrable narrative around ongoing corporate efforts to make education into a commodity, driven by large technology firms such as Google and Facebook and consultants such as McKinsey.

The attempt to uncover the history of what happened to Child Opportunity Zones in Rhode Island can be considered a counter-narrative, one where the successes are, for the most part, still hidden from view, even if students and teachers and administrators in the communities they serve know all about them.

Instead of focusing on "learning loss" during the pandemic, it might be more worthwhile to focus on "learning gain" through COZs in Woonsocket, Pawtucket, and Newport.

Part TWO

PROVIDENCE – A quick recap before we continue on our journey. In 1994, ConvergenceRI editor and publisher Richard Asinof and I found ourselves working in comparable jobs, pitching the good works of our respective employers, the United Way of Rhode Island and The Rhode Island Foundation.

Despite our previous training as “objective” [read that cynical] writers and journalists, we fell in “like” with a brand new R.I. Department of Education initiative called Child Opportunity Zones [COZs, pronounced co-zees].

Since our organizations were the key funders, Richard and I joined then-RIDE consultant Chip Young [“Phillipe” of the infamous Providence Phoenix columnists, “Phillipe & Jorge’s Cool, Cool World”], to tell the world about it.

Our mission, which we chose to accept, was to promote the idea that COZs could be the big answer – or at least one of the first initiatives in the nation – to link Rhode Island schools to wrap-around services to support school children: in their social-emotional needs; in their unaddressed health and mental health issues; in offering before- and after-school options; and in strengthening the family itself.

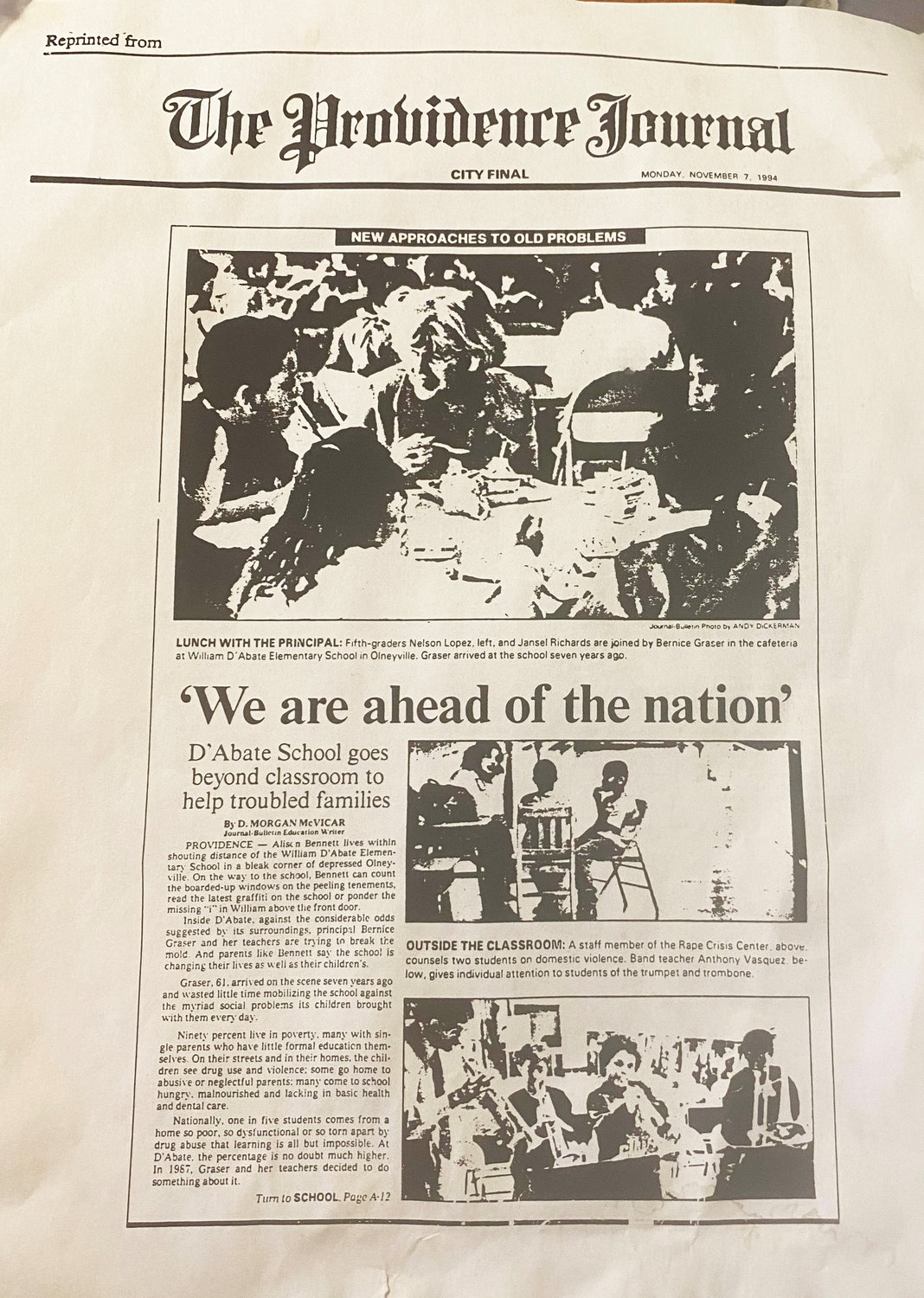

Our messaging worked: “We are ahead of the nation,” proclaimed the front-page headline in the Monday, Nov. 7, 1994, edition of The Providence Journal, with the subhead, “D’Abate School goes beyond classroom to help troubled families.”

The concept was straightforward: that by working together, RIDE and the R.I. Department of Health, in partnership with many of the state’s 37 school districts, funded through the Rhode Island Foundation and United Way, COZs might join with educators, administrators and exhausted social workers in proving that the answer to improving educational outcomes was investments in vibrant preventive services, rather than too-late crisis intervention. Call it making investments in place.

As detailed in Part ONE of the story, RIDE selected an assortment of nonprofits to run the initial 19 COZs that served some 13 Rhode Island communities. Not school districts, not RIDE itself, but nonprofits.

However, despite the lofty language and well-articulated goals that Richard, Chip and I were tasked with scripting, the disliked fact was that COZs were poorly funded from the start. Here’s where I pick up the story again:

Measuring results

Looking back, 27 years later, the historical record shows that the Rhode Island Foundation and United Way of Rhode Island apparently dropped out as funding sources. I couldn’t find mention of the COZs on either of their websites.

Further, RIDE provides no direct funding to the 10 COZs that have survived, 27 years later. Each of the surviving COZs does receive an annual legislative grant; the amount differs from year to year. It has ranged from a figure as low as $16,000 to the current funding year’s $40,000.

To put that in perspective, $40,000 is provided to connect an entire school district to each child’s world. Perhaps that’s why God created nonprofits.

The really good, the consistently mediocre, and the truly ugly history of COZs

For those of you who like the good news first, sorry. I’m starting with the moral of the story. [Or, as ConvergenceRI asks in its regular sidebar: “Why is this story important?”

It may be bad news for Richard, who tasked me out to find what happened to the COZs. On my journey, I uncovered this story line instead: that government and funders have a wicked short attention span. [Editor’s note: No worries, Rick. The story goes where it needs to go, where the facts take it.]

Here’s what my reporting found in the story about what happened to COZs. The funding sources may disguise it under the cloak of “seeding initiatives”; they may identify and choose grateful nonprofits [though, for the life of me, I don’t know why nonprofits should ever be described as “grateful.”] The selected nonprofits are then tasked to work on changing ages-old paradigms and problems with minimal funding, using “seed” funding that usually ends in three years or fewer.

What is the nonprofit supposed to do after that? Find other funding sources to preserve the program. As the director of one of the few remaining successful COZs told me: “We have about 50 different funders. All but three are one-year grants that I have to apply for again and again, with no guarantee. The others are three-year grants.”

No shortage of examples

COZs happen to be a great example of funding sources with short attention spans, but there is no shortage of such examples.

In education alone, as I pointed out in Part ONE, the state and foundations had once trumpeted: plans to establish dental programs in all the schools; plans to break up giant schools into smaller ones; plans to create affordable child care and after-school programs; and plans to deliver wrap-around social services that were based in school buildings. That was a quarter-century ago.

State Rep. Julie Casimiro, who has dedicated much of her adult career on behalf of disadvantaged youth, wrote in her preface to the 2019 report on the “State of Out-of-School-Time Learning Programs” in Rhode Island: “The evidence is overwhelmingly clear that learning and development of our students should not be limited to just school hours and I am looking forward to bringing this discussion to Rhode Island.”

Everyone always has the right things to say, but…

Uncovering the story about what actually happened to COZs turned into a bit of scavenger hunt. To give credit where it’s due, RIDE is the only governmental agency that actually lists COZs on its website.

The RIDE page implies that COZs are “a full-service community school model of school-linked family centers that bring schools, families and communities together to promote success in school for all children and youth.”

Further, the website page claims: “COZs are welcoming places in or near schools where families can access education, health and social service programs, supports and referrals to address barriers to student achievement at the highest levels.”

Despite the online rhetoric, while select COZs in Pawtucket, Woonsocket, Newport, and Bristol-Warren have brilliantly taken on many of those activities [and because people like former state Senator Mary Parella and Terry Curtin are driven and have become great fundraisers], no COZ looks like what RIDE defines it as.

As quickly as possible, RIDE’s online page about COZs passes the buck to three “related resources,” none of which it funds, although RIDE takes credit for “overseeing” the Nita M. Lowey 21st Century Community Learning Centers program. This is federal money for after-school and summer programs. [Nita Lowey was a New York Congresswoman honored for her work on the Congressional Joint Afterschool Caucus; R.I. Rep. David Cicilline sits on the caucus.]

While the 21st CCLC program sets plenty of standards for funding, Rhode Island doesn’t hesitate to pile on some more, including a six-section quality assurance requirement and seven pages of After-School Quality Standards.

And, while directly connected to the work expected of most of the COZs, anyone can apply to receive the competitive 21st CCLC dollars. And, they do, guaranteeing what we used to call “haircuts” at the Rhode Island Foundation – when we had to trim grants to spread the money among several applicants.

In the good news column, some 20 Rhode Island 21st CCLC sites serve nearly12,000 students per year in 46 schools in the core cities as well as Cranston and East Providence. The grants also support much-needed programming from homework assistance to GED training to youth development to the arts to family engagement. And, the best ones link the schools to the nonprofits to the community. Sound familiar?

The only Rhode Island evaluation of its 21st CCLC program listed online was from June of 2013. It showed a significant reduction in student absences and suspensions and improvements in NECAP reading scores. Given the current data around surges in chronic school absenteeism and poor standardized test scores in recent years, the data appears to be out-of-date.

The page reported that: “Data collection for the next phase of the evaluation is complete and data analysis is underway. This phase will assess how program quality impacts outcomes for students. Results will be posted here, as they become available.”

It is difficult to avoid being too snarky about the eight-year gap in calculating and publishing results.

Who’s on first?

The RIDE online page for COZs did list a contact; I’ve decided not to name names. She didn’t respond to my first call. A week later, I called again and sent here an email. She finally responded by referring my call to a public relations flack from RIDE; he emailed, asking if I could send written questions.

When I said no, I just wanted to talk to someone; he responded that the first time they could talk was “next Thursday.”

Translated, the RIDE online pages on COZs are out-of-date and inaccurate.

The funding sources

Both Richard and I left our jobs at the United Way of Rhode Island and the Rhode Island Foundation on relatively good terms, so this isn’t meant as a hit job.

As previously mentioned, a “search” on either organization’s website brings up no mention of COZ, or Child Opportunity Zones. The COZs are, however, mentioned in the 2019 Out-of-School-

Time Report sponsored by both the Foundation and the United Way.

The Rhode Island Foundation has had “strategic priorities” since I joined in 1993. The language is even stronger now, as the $1 billion-plus charitable organization identifies its three strategic priorities as: economic security, healthy lives, and educational success.

Even though these are the priorities among the grants the Foundation makes, the grant-making guidelines makes clear: “We make Strategic Initiative Grants for program support, organizational development and capacity building efforts, and advocacy or systems reform initiatives. We provide general operating support to organizations that are central to progress in one or more of the three strategic priorities described above. We rarely commit to multi-year grant awards.” [Emphasis added.]

And that’s for the Foundation’s strategic initiatives, for capacity building and systems reform, among other work.

In its most recent major announcement, the Foundation is on board with racial matters, no small issue in a state that played a major role in the slave trade. The Foundation has committed $8.5 million to creating the Equity Leadership Initiative to address diversity, equity, access, and inclusion. For three years.

Both the Foundation and the United Way are inspirational in describing the challenges and their efforts to meet them. I don’t write or speak [or perhaps think] that well, so kudos to my successors.

The United Way, for example, writes this about out-of-school learning: “We know that Rhode Islanders are impacted by the environment they live in, and they are impacted by the neighborhoods they live in. We are creating pathways for more youth of color to participate in high quality out-of-school time learning. We are also working to reduce the pathway to prison, using education as a key catalyst.”

In announcing LIVE UNITED 2025, its new strategic plan, UWRI reported: “The plan will require United Way of Rhode Island to go ‘deep, rather than wide,’ with investments and partners, to target the root causes that have thwarted Rhode Island’s ability to thrive. While we serve all Rhode Islanders in need, this plan will tackle Rhode Island’s great challenge, reversing the racial inequities that have plagued Rhode Island’s Black and brown communities for generations.

The strategic plan continued: “In order to ‘Live United,’ we must dismantle systemic, institutional, and historical barriers based on race, gender, sexual orientation, and other identities. We commit to leveraging all of our assets [i.e., advocacy, convening, fundraising, strategic investments, awareness building] to create a more equitable Rhode Island.”

The aspiration is more than laudable.

The worry

I worry for the nonprofits though, because the United Way’s action words for itself under “Goals” are “explore, engage, transform, drive, advocate, implement, raise, and refine.” Not “fund.”

And I can’t access grant information, past or present. The website requires that I register as a nonprofit [which I’m not] before I can see anything.

The bad: RIP and other disappearances

Yes, inadequate and unsustainable funding as described above are enough to challenge the quality and quantity of a nonprofit’s performance. But, to be fair, so are poor leadership and management, weak mission, and inadequate [or nonexistent] development and communications efforts.

By the time of Catherine Walsh’s 1998 report, four years into the effort, only 13 of the 19 original COZ Family Centers remained. Today, there are 10 COZs that remain is some form.

“Yes, it wasn’t only about the money,” a representative from one of the remaining COZs acknowledged. “Some just weren’t prepared to cope with such a profound task.”

Of those 10 COZs, several are superstars. Others are AWOL. I’m reluctant to name names; no doubt the ever-vigilant RIDE is keeping tabs. But of the 10, four have little or no social presence. They don’t show up in Google searches or, in the case of Providence [OK, I’ll name one], either on the grantee’s or Providence Schools website. No Facebook, Instagram, or web pages of their own. The question is: How are families supposed to find them?

At least one of them has morphed into the latest iteration of the COZ, namely Health Equity Zones (HEZ). In an eerie but familiar sameness, several years ago the R.I. Department of Health channeled federal dollars again into nonprofits eagerly lured into the promise of – wait for it – three years of funding to change the landscape of community health.

Calls to two of the more invisible of the COZs were not returned.

Other shortfalls.

In 2012, the COZs established the Rhode Island Partnership for Community Schools. Among the stated goals are to mobilize state resources, promote the community school model throughout the state, and offer timely and effective communications.

Although RIPCS has a director and a website [http://www.ripcs.org/index.html], the latter reports its last event took place on April 6, 2019. All the events before that are no more recent than 2016.

RIPCS offers a Facebook page as well. Notwithstanding that the director’s latest post is about a drive-thru pet food pantry in Warwick, most of the entries are germane, and from the most energetic individual COZs. Unfortunately, though the Facebook page was established three years ago, it has but 25 likes and 31 followers.

Translated, that means not even all the staff and administrators of the COZs themselves follow the page, let alone their respective school educators and families.

Finally, the really good

Terese “Terry” Curtin, executive director of Connecting for Children and Families [CCF] in Woonsocket lavishly credited COZs for her multi-service agency’s family-oriented approach.

A trained social worker, Curtin said: “My mindset is prevention, not crisis intervention. I wanted to focus my time and efforts on children and families from the get-go, not when it became impossible to turn things around.”

CCF was established in 1995, just one year after the Woonsocket COZ [with major support from The Rhode Island Foundation].

Curtin has braided together a powerhouse agency but is reluctant to take the credit.

“I continue to be deeply grateful for the model and ideals the COZs set; we could have been a very different organization without that vision,” she acknowledged. “The change has been wonderful. In the beginning, the schools treated us like visitors, saying: ‘Wasn’t it nice that we could offer something?’ Today, we’re seen as partners.”

And so they should be. With an array of funding partners and 21st CCLC grants for the past 20 years, Woonsocket’s COZ has a dedicated staffperson in each of three Woonsocket elementary schools, the middle school, and the high school, to link children and their families to resources. The program also offers after-school, summer, and day camp programs.

“Woonsocket COZ offers after-school academic enrichment and expanded learning opportunities serving approximately 1,800 students each year,” Curtin said. “Additionally, our COZ offers summer learning programs/camps to prevent summer learning slide, which is critically important for students in low-income communities,” she added.

If we are to take Curtin at her word [and why wouldn’t we?], the COZ model inspired the greater CCF to offer its full array of basic needs support, child care, workforce development, and more. [You can visit their website to read more at https://ccfcenter.org/]

In Pawtucket

Speaking of after-school programs, you may want to spend some serious time with another COZ pioneer, former state Sen. Mary Parella, the director of the Pawtucket COZ.

In pre-COVID times, the Pawtucket COZ has regularly offered after-school and summer programs for more than 1,500 students in all grades, she reports.

After-chool programs last 27 weeks, four days a week, and include both academic support and the fun stuff.

Add to that a summer camp plus a kindergarten orientation at each of the Pawtucket elementary schools to ease the transition for children [but mostly for parents, right?]. Parella’s crew appears to be doing a great job in going virtual with the after-school programs.

Children need to be raised in economically-stable homes, Parella insists, and so the Pawtucket COZ also offers adult education in English for Speakers of Other Languages [ESOL], pre-GED, computer, and job training. In non-pandemic times, the COZ/Adult Education Program runs a 20-hour per week daytime program and a three-times weekly evening program.

Like Terry Curtin, Parella gives everyone else the credit. “Partnerships are critical to the success of all our programs,” she said “The Pawtucket COZ has numerous partners for all aspects of our work. Many work directly with students in our afterschool, summer, and adult education programs. Partners include local universities, banks and community-based organizations, ranging from scouting to dance, theater, and the environment.”

We could go on and on, but we won’t. You can go online to read about Newport , Bristol-Warren, and Middletown COZs, all of which have easily findable and descriptive websites.

One final COZ success

Richard and I joined this adventure 27 years ago. The language around the COZs then was, while realistic and obvious, still aspirational and radical to Rhode Island.

Since then, the COZs have elevated the conversation to “Community Schools,” a universal term that goes beyond Rhode Island’s borders.

I asked Mary Parella and Terry Curtin their dreams if they had the budget I would wish them. On separate phone calls, they gave the same answer: a family coordinator in every school.