The strivers vs. the patricians

A tale of two competing narratives in “The Post”

As reported by ConvergenceRI, one such ad placement, on Nov. 4, 2017, on the digital platform of The Providence Journal, appeared without a disclaimer that it was an ad and not a news story.

Following two months of persistent questioning, ConvergenceRI learned that the ad placement was not a local buy; instead, it had been placed through GateHouse Media’s national advertising team. Further, it was not possible to track what other ad placements had been made by GateHouse Media on behalf of the Need To Know Network, according to The Providence Journal.

As GateHouse Media continues its aggressive engulf and devour strategy of purchasing daily newspapers in the region, and as the number of local reporters employed by The Providence Journal continues to shrink, the willingness of the corporate advertising team at GateHouse Media to place ads for the Need To Know Network highlights the problem of consolidated media empires that Ben Bagdikian warned about: media power is political power, both in editorial and advertising content.

PROVIDENCE – For someone who has spent more than four decades working in the salt mines of journalism, watching “The Post” was at times revelatory, resonant and uplifting: the crusading good guys won one against the tyrants of Babylon [a nickname used by journalist colleagues I knew in Washington, D.C., to describe the oppressive regimes of the federal government under several Presidents, borrowed from the lyrics of Bob Marley].

The heroine in the film was the publisher of The Washington Post, Katharine Graham [Meryl Streep], who made the decision to print the Pentagon Papers leaked by Daniel Ellsberg after The New York Times had been ordered to stop publishing them, going against the advice of her lawyers and board members.

At the moment in the film that Graham made the decision to let the presses roll, the audiences at numerous showings were reported to have broken into exuberant applause and cheers. [Mine did not.] It was very much a made-for-Hollywood, feel-good, hopeful ending.

Yet, at the root of “The Post” in its retelling of the story about the publishing of the Pentagon Papers, there was the pervasive myth about the crusading news establishment: the pursuit of truth, justice and the American way, in the best Clark Kent and Lois Lane fashion – veritable comic book superheroes making the leap onto the silver screen to save us all [from ourselves].

Democracy dies in the darkness, the current slogan of The Washington Post proclaims. Still, the shadows of darkness and tyrants pervade our world, and the strong undertow of the dark side of those forces grows stronger, despite an aura of self-congratulation to be found in “The Post.”

Call it a tale of two competing narratives.

Calculus of electoral politics

Watching “The Post,” the parallels to our current time of Constitutional crisis were hard to miss: a tendency by the media to defer to government officials, to repeat the lies they told about Vietnam that flowed so easily from their lips, tied to the calculus of electoral politics and the protection of the elevated status of the wealthy and the powerful, to divide the world into hawk and dove, the vocal minority vs. the silent majority, love it or leave it. Sound familiar?

But the film, to its credit, did not attempt to simply portray the editors and publishers of The New York Times and The Washington Post as heroes and the government officials and apparatchiks as villains; it acknowledged the complicity of the intimate relationships between elites. Change places, and handy-dandy, which be the justice and which be the thief, as Shakespeare once asked in King Lear.

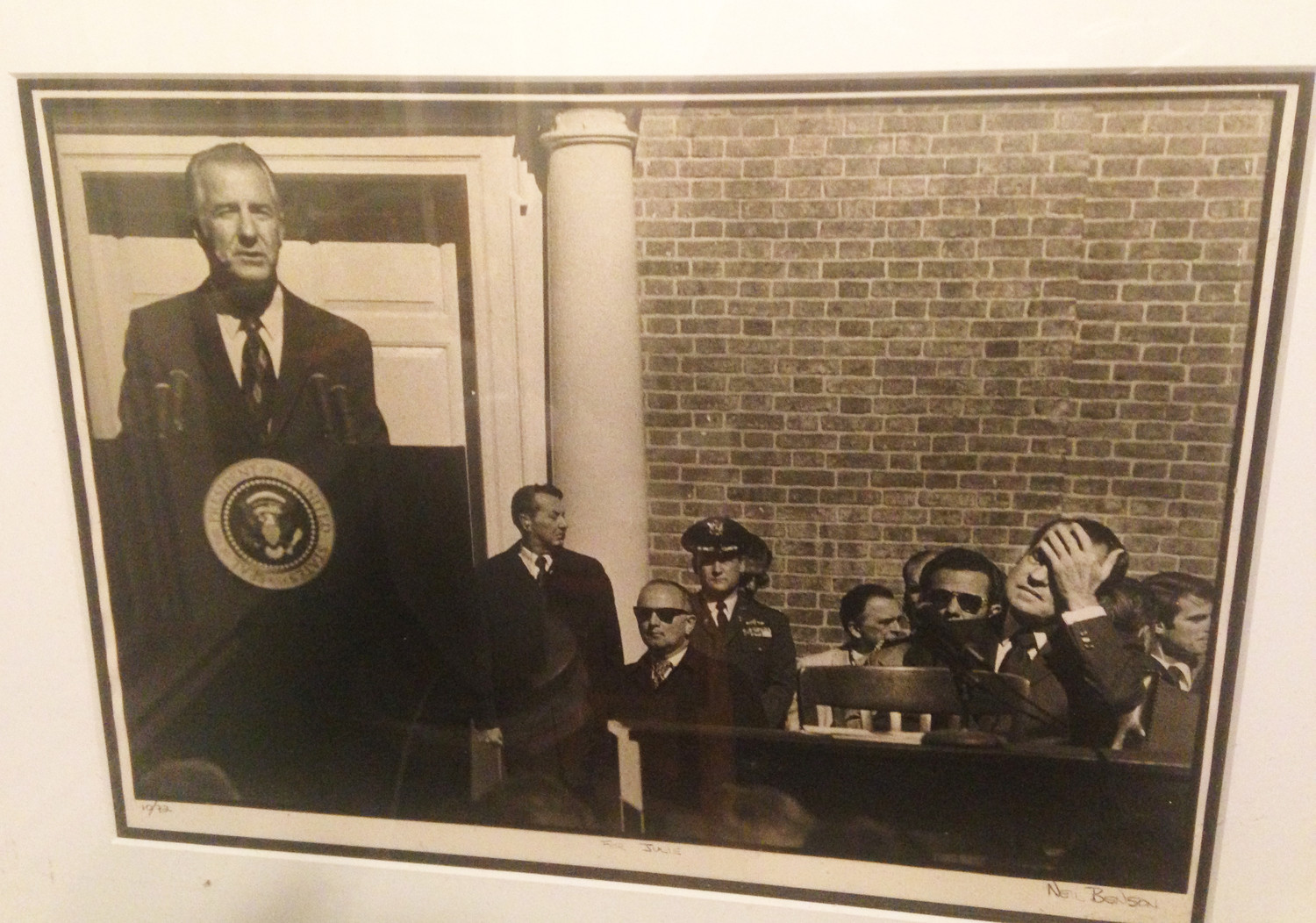

And, as the sharp dialogue between the characters of Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee [Tom Hanks] and his wife Tony [Sarah Paulson] revealed in the film, looking at a framed photograph of the two of them together with President John Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy, there was a steep personal price to pay for gaining such access to the powerful, reflected in their own complicity in the keeping of the secrets, lies and deceptions.

As A.J. Liebling once said, which I believe I heard paraphrased by Katherine Graham’s character in the movie: “The only guarantee of a free press is to own one.”

Conflicted

Watching the film, for sure, filled me with moments of surreal sensory memories, much like inhaling the aroma of freshly baked bread coming out of an oven: the way an entire building would shake and rumble when the presses began to roll, the setting of blocks of type in hot lead on a linotype machine, the clatter of typewriters and teletype machines, the copy editor taking pencil to paper, the pressures and camaraderie of working on ridiculous deadlines in smoke-filled rooms, the penetrating chemical smell of the ink on the presses, the adrenalin rush in grabbing the first edition of the newspaper to hit the streets, the black ink rubbing off and smudging your fingers.

[Call it le temps perdu; linotype machines were mechanical dinosaurs, relics from an industrial age long past and buried; most presses today operate far, far way from the editorial offices; smoking is prohibited, typewriters are non-existent in newsrooms, and most everything is performed on digital platforms.]

I was not alone in reliving such memories watching the film: Mike Stanton, a former award-winning reporter at The Providence Journal who now teachers journalism at UConn, tweeted after seeing “The Post”: “Loved the clattering typewriters & pneumatic tubes in the newsroom. You could smell the ink in their blood.”

Other scenes from the film, however, left me overcome with unexpected emotions of loss and anger, which recalled traumatic scenes from my own earlier days as a journalist: the accurate portrayal of the smug arrogance of New York Times executive editor Abe Rosenthal, for instance.

Rosenthal was the apparent decision-maker at The New York Times who had killed my magazine story about the anti-nuclear movement in America the week following the nuclear accident at Three Mile Island in 1979, so I had been told.

I had been on assignment for the New York Times Magazine, covering the anti-nuclear movement in California and its fight against Diablo Canyon; the story was scheduled to run in mid-April. In mid-March my deadline had been moved up; then I was ordered to take the next red-eye out from San Francisco; unshaven, disheveled, without any sleep for 24 hours, I had to wait for more than an hour in the foyer of Ed Klein’s apartment on Park Avenue to hand deliver the story on a Sunday evening.

The next day, on Monday, Klein killed the story; he told me that Jane Fonda and Tom Hayden represented a greater threat to America than nuclear power plants, an opinion borrowed from George Will. My individual editor at the magazine, Wendy Moonan, called me Tuesday afternoon to tell me that the only way my story would ever see the light of day was if there was a nuclear accident. The next day, March 28, the partial meltdown at Three Mile Island occurred.

All of sudden, my story was back in the queue, I was ordered to take the weekend and to rewrite the beginning of the story to incorporate the Three Mile Island accident. But, when I handed in my story late Monday afternoon, Klein, without even reading it, rejected it once again, telling me that there was no story anymore. Rosenthal, according to my sources [a New York Times vice president], had killed the story from on high.

What a cinematic scene followed in Klein’s office: “What do you mean there’s no story?” I had responded, yelling, “It will be like the Tet Offensive.” Another editor in the meeting, Marty Arnold, yelled back: “Do you know who really won the Tet Offensive? We did.”

Meanwhile, Moonan was busy kicking me hard underneath the table, trying to get me to shut up.

The takeaway: my piece ran the next week as the cover story in The Village Voice. I had indeed written a story that was worthy to tell.

Credibility gap

“The Post” begins with Daniel Ellsberg being asked to join Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and Robert “”Blowtorch” Komer for a briefing during a flight returning to Vietnam. [An important footnote not shared in the film: Komer, the CIA professional tasked with winning the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese, was responsible for “pacification” as well as the Phoenix program, a CIA-led effort of targeted assassination that was estimated to have killed as many as 40,000 Vietnamese.]

McNamara asked Ellsberg whether he thought the war in Vietnam was going in the right direction. Was there progress being made? Ellsberg answered, that despite a major increase in U.S. troops, the situation on the ground had not improved. To Ellsberg and to Komer, McNamara acknowledged that Vietnam had become a quagmire.

Yet, at a news briefing upon landing, McNamara smiled and lied and said that progress was being made, that he was optimistic about the war.

One of McNamara’s trusted aides wrote in a 1965 memo that was included in the Pentagon Papers and repeated in jarring fashion in “The Post”: 70 percent of the U.S. purpose in Vietnam was “to avoid a humiliating defeat.”

Missing from “The Post” and from the documentary on Vietnam by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick was the story of Ellsberg’s tipping point in his decision to release the Pentagon Papers: his dialogue with Randy Kehler, a conscientious objector about to go to jail – a narrative that did not fit conveniently into the messaging of either film. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “A willingness to stand up and say no.”]

The truth about the Vietnam War had been hiding in plain sight for years: the news media had been complicit in reporting the lies of Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon and their functionaries about the war. Rarely did the newspapers and broadcast media ever dare say, in a headline, that the President was a liar [until, of course, the tapes made in the Oval Office by Nixon were revealed to the public, after the Supreme Court ruled against him, forcing him to release the pivotal tapes as evidence, leading to his impeachment].

It was not for lack of trying by many of the reporters on the ground in Vietnam covering the war. It was not for a lack of coverage, mostly in the alternative media, attempting to question the prevailing narrative. [A case in point was in October of 1972, when Nixon’s Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger declared that “peace was at hand” in Vietnam; it resulted in an irreverent front-page headline in The Drummer, the alternative weekly in Philadelphia, asking: “Is peace a hand job?”]

Beyond the breaking news

Journalists, when they look into the mirror, tend to see themselves and their colleagues as heroic and courageous – and sometimes they are. But, much as fish, they do not see the water they swim in, nor cover the competing narrative of stories that do not fit into their own self-image [or selfie].

All too often, journalists are willing accomplices, mouthpieces for the corporate powers that be and the dark shadows they cast. As Ben Bagdikian [Bob Odenkirk in “The Post”], assistant managing editor in 1971 at The Washington Post who had retrieved 40,000 pages of the Pentagon Papers from Ellsberg, reportedly told his journalism students at the University of California Berkeley: “Never forget that your obligation is to the people. It is not, at heart, to those who pay you, or to your editor, or to your sources, or to your friends, or to the advancement of your career. It is to the public.”

Bagdikian, a survivor of the Armenian genocide at the hands of the Turks, wrote “The Media Monopoly” in 1983, in which he presciently argued that the increasing concentration of the media in the U.S. in the hands of corporate owners threatened freedom of expression and independent journalism, warning that “media power is political power.”

If Graham was the patrician, Bagdikian was the striver. Imagine if the narrative of “The Post” had been written instead around Bagdikian, not Graham. It would have been a far different story altogether, a dramatic, action-packed film that “The Post” could never be.

Bagdikian’s parents, fleeing Turkish forces, thinking their infant son dead, dropped him in the snow in the mountains, only to pick him back up when he began to cry. Bagdekian won a Pulitzer in 1953 with The Providence Journal for his coverage of a bank robbery in East Providence; as a foreign correspondent, he covered the Suez War in 1956, riding in an Israeli tank; in 1957, he covered the civil rights crisis in Little Rock, Ark., and in 1972, he went undercover at a Pennsylvania state prison, pretending to be a murderer, to write an exposé on deplorable prison conditions. Bagdikian also served as The Washington Post’s first ombudsman, only to be fired by Bradlee. [In 2016, he was inducted into the Rhode Island Hall of Fame.]

In 1996, Bagdikian described the treatment of news about tobacco and related health issues as “one of the original sins of the media,” because there had been for decades suppression of medical evidence.

In “The Post,” however, Bagdikian was often portrayed as a kind of bumbler, spilling his coins when trying to use a pay phone to call Ellsberg, or having to carry the 40,000 pages of the Pentagon Papers by buying an extra seat on the plane, or arriving by taxi at the patrician Georgetown home of Bradlee to deliver the massive bundles of copied pages.

“The Post” may not win an Oscar this year; it is highly unlikely that the current President will ever screen a showing of the film at the White House. But it is worthy of becoming part of our conversation, not just for what it portrays, from the privileged, patrician point of view, but for what gets left out of the narrative.