Why narrative matters

A lesson or two on what it takes to disrupt the dominant narratives of our lives

I then asked how many people who were attending the discussion knew that a group of Hampshire College students, in the early 1970s, had designed one of the first college academic curricula around the Holocaust. It seems that important bit of the school's historical narrative had been swallowed up.

One of the more fascinating conversations that occurred during the Hampshire reunion was with Eliot Maxwell, who had, along with Ira Magaziner, had helped to revise Brown University’s curriculum in the late 1960s. Maxwell then moved to Hampshire College, where he assisted the college in numerous capacities around admissions and fundraising.

Maxwell asked me about what I thought about R.I. Treasurer Seth Magaziner’s campaign for Governor [Seth is Ira’s son.]

Despite the crowded campaign field, I said that “less may prove to be more” and that Magaziner’s campaign had been too “noisy,” in my opinion. I recounted how the campaign launch had been marred by Magaziner’s failure to answer media questions at the initial event – an episode that Maxwell said he had not heard about.

I suggested that given the crowded field of candidates, the ground game would be crucial. In terms of messaging, I also thought that Magaziner would do better to be perceived as listening, rather than talking at people.

AMHERST, Mass. – This weekend, I presented a talk about media disruption and storytelling at the 50th anniversary celebration of Hampshire College. I had been one of the 251 students in the first entering class in 1970.

In my presentation, I spoke about the importance of storytelling, saying that our own personal stories were our most valuable possession, and the sharing of those stories was what made us human, helping to build engaged neighborhoods and communities.

I then shared my own story about ConvergenceRI, and my belief in the importance of creating a source of accurate reporting that was unflinching in asking questions, and in seeking convergence and conversation, refusing to reprint news releases as news.

I also talked about the importance of creating a narrative – and how Hampshire’s own history was not about what had gone right, but rather, what had gone wrong – and the diligence of its students in figuring out what to do when nothing seemed to work right, a kind of problem-solving entrepreneurial approach decades before it became a popular term of our lexicon.

The story of Hampshire College’s survival is still being written. The board of directors had mistakenly hired a new president in 2018 whose mission, she thought, was to dissolve the school and have it merge with the University of Massachusetts Amherst. She resigned in March of 2019, after plans of her coup went awry, but not before enormous damage had been done.

The students had rebelled; the former alum and students did, too, and the college is now being reborn, recommitted to a transformative vision of higher education, underwritten by a fund-raising campaign spearheaded by alums, filmmaker Ken Burns and rocket scientist Lucy McFadden, serving as co-chairs. The campaign seeks to raise some $60 million to secure that future. The school is more than a third of the way there, a remarkable achievement.

At the community dinner on Saturday night, the new president of Hampshire College, Ed Wingenbach, thanked the nearly 1,000 folks attending the reunion. The Hampshire community, Wingenbach said, “had saved the college at its moment of deepest peril.” He received a prolonged, standing ovation.

The college reborn has created a strong counter-narrative to the advertised corporate vision of higher education – a belief about the importance of arts and humanities in framing the questions critical to solving the biggest challenges we face – asking the right questions about climate change, disrupting and dismantling white supremacy, redefining truth in a post-truth era, and developing strategies on how best to heal from pain and trauma.

“The biggest blind spot,” Wingenbach continued, “ is the belief that our problems can be solved by technical experts.”

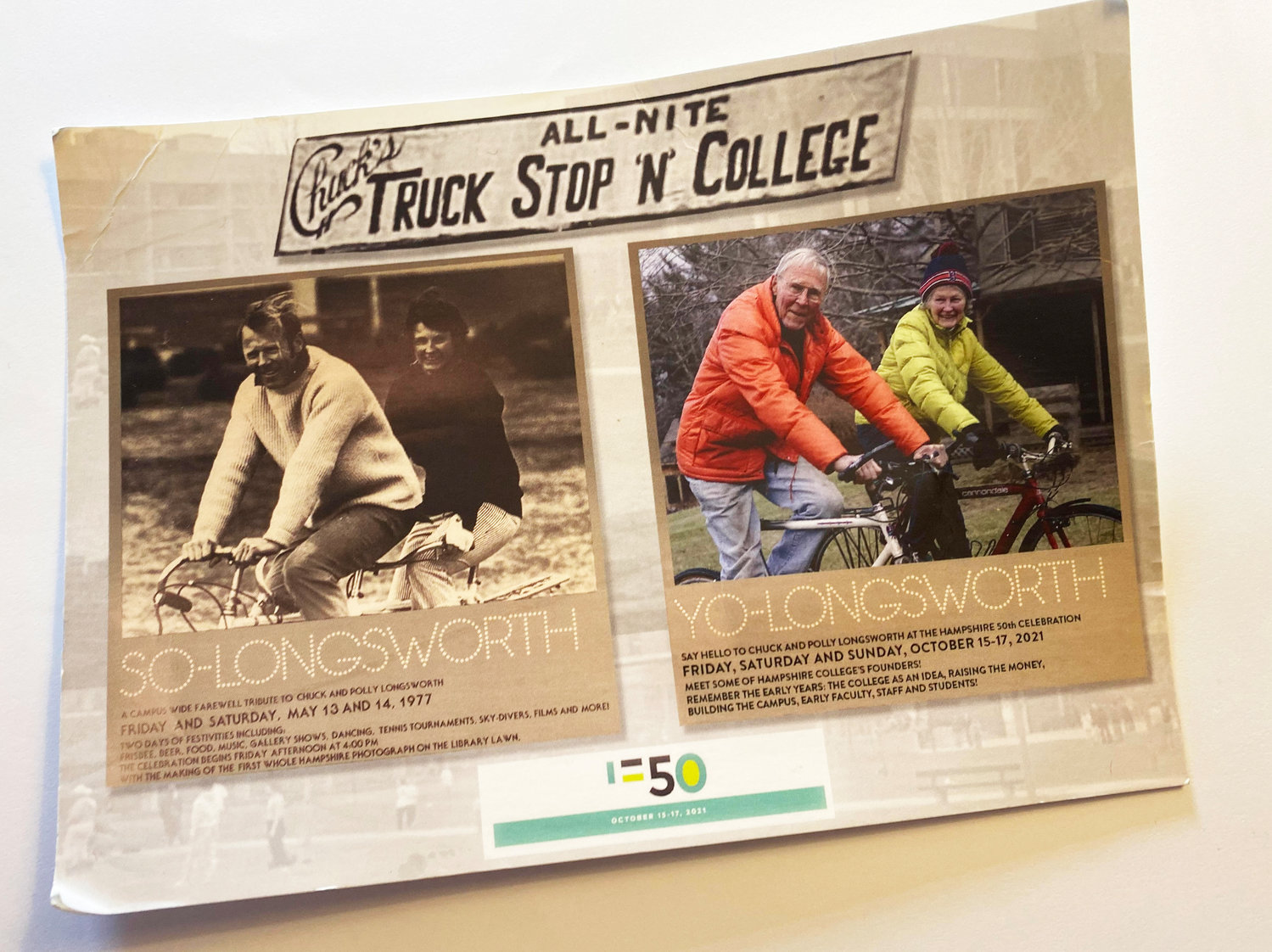

Editor’s Note: Hampshire still maintains a healthy sense of humor, humility and irreverence about itself: the carry-along bag given to reunion participants promoted a slogan that had once been painted over the entrance sign to college in 1971, in a protest by students, “Chuck’s All-Nite Truck Stop ‘n’ College,” referring to then college president, Chuck Longsworh.

Chuck and his wife, Polly, attended the reunion, and were re-introduced [by me] to the student artist, Dorli Demmler, who had painted the irreverent sign 50 years ago. Polly insisted that Dorli autograph both hers and Chuck’s bags.

Framing the questions around narrative

On the drive to the reunion on Friday afternoon, I had been pondering questions around narrative. Before leaving, I had conducted a 15-minute interview, via phone, with Gov. Dan McKee, after six months of requesting such a one-on-one interview.

What had taken six months of persistence with Gov. McKee to achieve followed six years of denial by former Gov. Gina Raimondo, who had refused to be interviewed by me, one-on-one, even after shaking my hand and agreeing to do so, twice. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “The interview that never happened with Gov. Raimondo.”] Call it a badge of honor I wear proudly.

In the interview, McKee had talked about the new working paper he was releasing, his vision for Rhode Island in 2030.

Within the brief 15-minute conversation there were moments of breaking news: After more than a decade of the state trying to expand Medicaid in order to provide health coverage for all Rhode Islanders, regardless of economic status, McKee said he would be endorsing a new strategy of shrinking the Medicaid population, not by throwing peoople off of Medicaid, but by putting the emphasis instead on paying workers more money, increasing their earning power, so that they could afford “traditional” health insurance.

Gov. McKee also persisted in promoting his “mistaken” narrative, in ConvergenceRI’s opinion, that the more than $2 million in cuts by the R.I. Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities, and Hospitals to recovery programs were not “cuts,” but rather the results of federal funding sources that were being sunset. He voiced full confidence in the agency’s director, Richard Charest, and anger at the walkout by recovery community members at the Governor’s Task Force meeting in response to the cuts.

In case you missed it, in a rare victory, the recovery community had won and the cuts were rescinded. [See links below to ConvergenceRI stories, “BHDDH cuts more than $2 million in funding for recovery programs,” “Hard of hearing: BHDDH’s Charest and Gov. McKee appear to be tone deaf,” and “Recovery community creates sea change in laws, policy.”]

Reclaiming the corporate narrative

The bigger problem, I ruminated about during the drive to Amherst, Mass., the home of Hampshire College, was the news release that had been put out by the Rhode Island Foundation about its decision to award some $250,000 to purchase emergency supplies of naloxone.

Any contribution to further the availability of naloxone, and its trade name, Narcan, is an important act, for sure. And, make no mistake, the continued generosity of the Rhode Island Foundation during the pandemic has been critical in keeping the safety net stitched together.

But, in its news release promoting the grant to support he purchase of Narcan supplies, it seemed to me that the Rhode Island Foundation was attempting to rewrite the narrative, removing the victory won by the recovery community from that narrative.

The new financial gift was announced in a news release on Wednesday, Oct. 13, with the headline: “As supply of Narcan dwindles, Rhode Island Foundation awards $250,000 grant to fill the gap until a permanent source of funding can be found.”

One of the big problems with the news release and the grant was its failure to mention the fact that R.I. Attorney Peter Neronha had secured $1 million in financing for naloxone purchases – four times the amount being gifted by the Rhode Island Foundation, in response the recovery community’s needs, as documented in ConvergenceRI.

When asked about the $1 million in funding by the Attorney General, Chris Barnett, the public relations spokesperson for the Rhode Island Foundation, clarified the message: “The $250,000 is additional funding.”

The problem with the narrative, of course, is that nowhere in the news release, nor in any of the news coverage that followed, was there any mention of the $1 million in funding. Why was that?

When asked about the lack of mention by the Rhode Island Foundation about the $1 million contribution made by the R.I. Attorney General's office to buy naloxone, spokesperson Kristy dosReis took the high road and replied: “We were glad we were able to help in the efort to address this critical community need!”

Perhaps it was because of what had been the source of the $1 million – it was part of a $2.5 million settlement paid out by McKinsey and Co. for its role in turbocharging the opioid epidemic on behalf of Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “The high cost of consulting firms making policy.”]

The other big problem with the news release, glided over by the Rhode Island Foundation, was the source of the $250,000. “The funding for the Foundation’s grant comes in part form the Behavioral Health Fund, which was created with funding from Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Rhode Island,” the news release said.

What had been left out of the narrative was the reason that the Behavioral Health Fund had been created. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “New behavioral health fund financed by settlements from insurers past bad deeds.”]

The money had come from settlements, after the R.I. Office of the Health Insurance Commissioner had conducted “market conduct examinations” of the major commercial insurance companies operating in Rhode Island. The examinations had found that there were “violations” committed by the insurers related to enforcement of state and federal “behavioral health parity” laws, focused on measuring compliance with regulations related to the coverage of mental health and substance use disorder services.

As ConvergenceRI had reported: Translated, in the midst of a devastating epidemic of opioid addiction and substance use disorders, which has claimed more than 300 lives a year for the last [five] years and disrupted thousands of lives and families, Rhode Island’s commercial insurers have apparently chosen to focus on wringing more money from the system rather than investing in better coverage, according to OHIC’s findings.

Beyond the apparently successful attempt by the Rhode Island Foundation to reclaim the narrative, positioning the benevolence of corporate philanthropy as the life-saving source of intervention around combating the opioid epidemic, the other big problem was the way that the story was covered by the local news media in Rhode Island, including The Boston Globe and The Providence Journal, among others, which had both been negligent, if that is the right word, in ConvergenceRI’s opinion, in covering the successful intervention by the recovery community and how they were able to get more than $2 million cuts rescinded. Why was that?

38 Studios redux

On Friday afternoon, there was a major traffic jam on the Massachusetts Turnpike heading west, forcing me to shunpike my way along Route 20, allowing for more time to ruminate about narratives.

For instance, the entrance by former CVS executive Helena Foulkes into the already crowded primary for the Democratic nomination for Governor in 2022 has brought with it another recurring problem with the corporate narrative about what had happened a decade ago when a bad decision had been made to invest state economic development funds in a fledgling video game company run by Curt Schilling.

Much of the current media brouhaha between Foulkes and former Gov. Chafee, as portrayed in the news media, involves whether or not state film tax credits should have been given to bail out the failing 38 Studios firm, with each giving a different memory of events. Chafee opposed them, Foulkes supported them, and the news media is now having a field day replaying the incident, as if they were all sportscasters looking at instant replay to analyze a provocative call. Tastes great, less filling.

But, in ConvergenceRI’s view, it is all part of a misleading narrative about what happened. To fully understand the fallacy of the state’s investment in 38 Studios, it requires a better understanding of how an effort to recapitalize a small business loan fund had been apparently hijacked by former Gov. Donald Carcieri – and then was pushed through the R.I. General Assembly by Keith Stokes, the former director of what was then known as the R.I. Economic Development Corporation. [Stokes is now serving as the economic development director for the City of Providence.]

The ghost of job creations metrics past

Here is the part of the story that always seems to get conveniently left out of the media conversation and the narrative.

As ConvergenceRI wrote in 2014: At the end of day, the metrics don’t matter, argued J. Michael Saul, [the former] deputy director of the state’s economic development agency then known as the R.I. Economic Development Corporation. “It’s all about jobs – jobs, jobs, jobs, jobs, jobs,” Saul said, dismissing the reporter’s questions about benchmarks for measuring the success of the investments.

Saul’s arrogant response was part of a lengthy, two-hour-long interview that took place at the agency headquarters during the first week in March of 2010.

Saul was promoting the concept of a new state bond – a $50 million small business loan fund – an idea that he said had already been floated with key legislators and EDC board members.

Some of the money, Saul told the reporter, would be used to recapitalize the federal Small Business Loan Fund that was now depleted, having run out of money to loan.

The interview took place less than a week before Gov. Donald Carcieri’s fateful conversation with Curt Schilling at a fund-raiser at Schilling’s home in Mansfield, Mass.

Soon Carcieri would transform plans for the $50 million state bond to support small businesses in Rhode Island, increasing the amount of the fund to $125 million, with $75 million of that earmarked for Schilling’s 38 Studios deal.

Saul, along with agency director and co-defendant Keith Stokes, later settled in court a lawsuit brought by the state of Rhode Island alleging fraud for failure to inform the R.I. EDC board of directors about the full financial risk of the deal.

The ConvergenceRI story continued: “Lost in the onslaught of 38 Studios disaster was the gaping hole in Saul’s “jobs, jobs, jobs” response: the reality was that the agency had failed to track and tabulate the job creation data for the previous five years – from 2005 to 2010 – of the loan fund’s operation.

Instead, it relied on data supplied by the companies at the time when the loans had been granted, with the projected numbers of retained and new jobs. Although a number of companies receiving loans had gone out of business and defaulted on their loans, their numbers were still being included in the agency’s job creation totals for the loan fund.

Companies in Rhode Island that received some $16.7 million in loans between 2005 and 2010 were asked once a year to update the number of people employed, but only about half of them complied, according to agency officials. “We do make an annual request to companies for updated information, however only about half of them consistently report,” Sean Esten, then financial portfolio manager of the agency’s Small Business Loan Fund, told the reporter in 2010.

“We’ve never put that information into a spreadsheet to track it,” Esten said. “There’s a big pile of that. I don’t have time for that.”

Indeed, the story continued: It was Esten’s memo complaining about the lack of financial scrutiny in the 38 Studios deal, saying that a $10,000 micro-loan received more financial scrutiny than the Schilling deal – a concern that was allegedly squashed by Saul and Stokes – that was considered potential key evidence in the fraud lawsuit.

Transforming the dominant narrative

The message to take away from the celebration of Hampshire College’s 50th reunion was the continuing belief in students’ desire and ability to design their own education. In the last year, there have been more than 10,000 new inquiries from potential students about attending the college, putting the goal of attracting an incoming class of 1,200 students by 2025 within reach, according to Wingenbach.

When the school began in 1970, its policy of no grades and its belief in designing curriculum around cross-disciplinary studies – and allowing students decide the content of their educational path – was considered innovative and experimenting. In its first two years, the school was harder to get accepted at than Harvard University, attracting students – and faculty – who wanted something different from their higher education.

The path was not always an easy one, and there were many failures to go along with numerous success stories. For those of us in the first class, the pioneers, it was always a difficult journey. [See link below to ConvergenceRI story, “Let us now praise the importance of asking questions.”]

Still, there was an important lesson to be learned at the 50th reunion of the first class at Hampshire College – one that is similar to the story about how the recovery community in Rhode Island stood up to an entrenched bureaucratic elite, and won.

It is this: The dominant corporate narrative is crumbling – in health care, in education, in economic development, in politics, and especially in the news media. What will take its place is a narrative still being written – at Hampshire College and here in Rhode Island. Stay tuned.